Chapter Eight

…I stayed there sitting for some time, with no idea where to go, or where to find the Central Department for Organization, the Department for Unification, or any reception center. I had not a cent in my pocket, and looked like a zombie. I was too weak to go anywhere. With great effort, I dragged myself to a park bench nearby.

Hằng and I had gotten to know each other before I went to the South (“Đi B”). We came to each other through friendship and mutual respect. If I had remained in the North, we might have become closer still, more committed, and would eventually have become husband and wife. I mention my feelings in this connection, because, when I was dumped into Unification Park, the sight of young couples strolling here and there gave me a pang of loss inside; I felt inferior; I was in pain.

Unification Park was a place where Hằng and I had gone together for walks before I left for the warfront. But now look at me! Even a street beggar could not have been more dirty and foul-smelling than I.

Before I left, or to speak more precisely, before I went to the South, I had spoken to Hằng (who later on became my wife) as follows:

“Look my dear, in the places I’m going to, the fighting is so terrible that out of ten people who go there, very few come back alive. And this applies especially to cameramen like me, because my work is to film the war. I’ll have to stand up to shoot scenes, not hide in shelters or trenches. Many cameramen have died, so don’t wait for me. We must say goodbye now, and farewell for good. You’ll have your own road to travel, every girl has one spring time only that must not be wasted…”

Having spoken thus, I also wrote her a letter with the same content. I had Đặng Trần Sơn deliver it to her home. The most important thing was that I really didn’t want to make a girl wait for me hopelessly. After that, there was a long absence of news, as I had gone to the South where bombs rained and bullets flew…

That was the reason we parted. Even if I had returned, but was missing an arm or a leg, that would just have been another reason to discontinue the relationship, to be free of any obligation. Thus I made the decision so we wouldn’t be bothered with such things…

There was no hope for anyone to survive and return. When I went to the South, my mother was so worried and grieved that she lost her mind, placing a teapot on the stove and throwing ashes into it for tea, and forgetting to add any water to a pot full of rice when she put it on the stove to cook.

Since my elder brother Vĩnh died, I had become the oldest son, but I was leaving home at a time when my parents were already aged, and my younger siblings were still too young to make a start in their lives. Yet I had to grit my teeth and go. What else could I do? So I don’t like the nonsense stories that people make up nowadays, with such catch phrases such as “I was heroic, I hated the enemy, I had this point of view, or that political stance, etc.” But if I were to speak my mind honestly and frankly, people might look at me as if I were a madman…

My elder sister’s home was on Hoà Mã Street nearby. I reasoned that it would be best to go there first. My sister Muội had married a man named Mạc, so we called her “chị Mạc” (“Sister Mạc”). She was born in 1939, so she was a year older than me. She was the last child of my father’s first wife, and was a full younger sister of my brother Vĩnh.

Looking at the cyclos passing by, I wasn’t sure that any of them would give me a ride.

“Xich lô…”

The driver gazed at me fixedly, then went on, peddling silently down the street.

An older driver came peddling by.

“Bác Xich lô!” (addressing him politely as “uncle”)

He looked at me hesitantly.

“Uncle, I’m going to Hoà Mã Street, no.52…”

“You have money?”

“Certainly. I don’t have it on me right now, but my family has it over there. It’s not very far.”

As I was about to step into the cyclo, he removed the mat on the seat. Too bad! The mat wasn’t all that clean after all… so I had to sit on a bare wooden plank. With my shrunken hips with protruding bones resting directly on the wood, I felt pain throughout my body whenever the pedicab gave me a sharp jolt.

We reached no. 52. I saw sister Mạc walking around right inside the steel fence. I called out:

“Chị Mạc!”

Four eyes gazed at each other. She didn’t even ask “Who’s there?” but instead quietly retreated into the house. The cyclo driver asked,

“Could you be wrong?”

“No, that’s my sister! Uncle, do me a favor—knock properly at the door and call for Mrs. Mạc. Tell her that a close relative of hers is here.”

The cyclo driver did as I instructed. She stepped out of the gate again and stood for a moment fixing her gaze on me. When she recognized her younger brother, she was utterly confused, and the driver didn’t know what to do either. She led me into the house and drew out a plank-bed for me to lie on. I noticed that the plank had Chinese characters on it—it had formerly been half of a set of paired-couplet placards (câu đối – Chinese inscriptions on a pair of vertical planks often seen on both sides of the family shrine). During the land reform, our family was so afraid of being denounced as rich that we had sawed off the planks and made a bed from them—on the other side the old inscriptions were still there.

My brother-in-law Mạc had gone elsewhere. My sister and I lost ourselves in conversation. We spoke incoherently, but the cyclo driver was nevertheless able to catch the drift of everything we were saying. Suddenly I remembered that he was still waiting.

“Can you give me ba hào (thirty cents) to pay the driver?” I asked my sister.

“I’m sorry,” said the driver. “I thought he was a returnee from a re-education camp or an escaped convict so I didn’t really want to take him. Now that I know the story, I just want to help. I won’t take any money.”

We tried very hard but he refused to take the money. Then he bade us goodbye and slowly peddled away. I told my sister, “I came back from the frontline, but they just dumped me down at Unification Park. I don’t know where my offices are. Let me stay here for the time being, while I find out where they are.”

My brother-in-law Mạc returned.

“Oh, what happened? Let him take a bath first!”

He gave me his two best suits of clothes. Back then each person was allowed to purchase only five meters of cloth each year. I have never seen such a generous brother-in-law in all my life—and he was like that from the beginning. Later, when my father breathed his last, this brother-in-law held him in his arms.

Brother Mạc sorted out my stuff and took out all the boxes of film. As for the other miscellaneous items, such as an empty can and an old cloth sack… he threw them all into the waste basket. He heated a huge pot of water, just like the ones used to boil bánh chưng (special sticky rice cakes cooked for Tết), so I could bathe and put new clothes on.

He ran over to the office where he worked, the city busing management board, and made a phone call to Nam Định.

My father was a big man, 1.8 meters tall, with a resounding voice. He very seldom shed tears. From Nam Định he went straight to his daughter’s home, where he saw his son lying there, with two feet as white as paper. He knelt down, embraced his son’s feet and wept… That was the second time in my life that I saw my father weep. The first was when he embraced Vĩnh’s body on the day he died in the sweeping operation of 1949. My father died in 1975—thirty-seven years ago already.

In any case, I had to make contact with my office. I had no idea how to begin. Anh Mạc made a few phone calls and found all the contacts for me. Nearly an hour later, an official jeep arrived.

They delivered me straight to the “Việt-Xô” (Vietnamese–Soviet) Friendship Hospital. From the emergency room to the transfusion room, I kept on hugging the sack of film. My red blood cell count was two millions and eight hundred, and my weight was forty-two kilograms. For three months running, they gave me blood transfusions and protein injections! Only after half a year of medical treatment did I return to a roughly satisfactory condition.

Almost immediately upon my arrival at the hospital, I tried to contact the Cinema Department concerning the film. As far as my position was concerned, I belonged to the Department for Reunification, but this department didn’t have a clue about film.

When the Cinema Department learned that a journalist just came back from the front with undeveloped film, they immediately sent someone to the hospital to receive the film, but I refused to give it to him. It had to be someone with a clear responsibility and position. This was no joking matter.

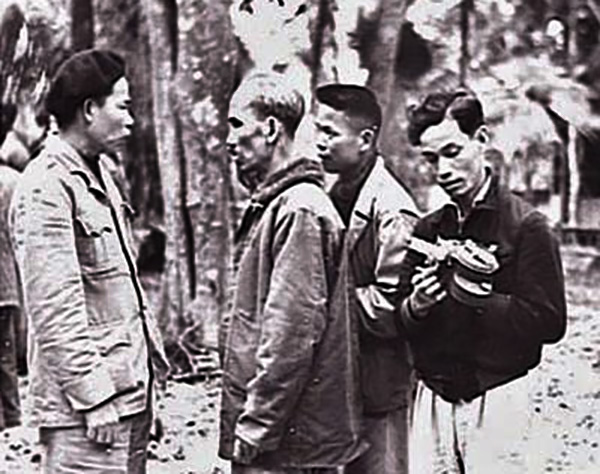

Mr. Nguyễn Thế Đoàn (holding a camera) during his days in Việt Bắc…

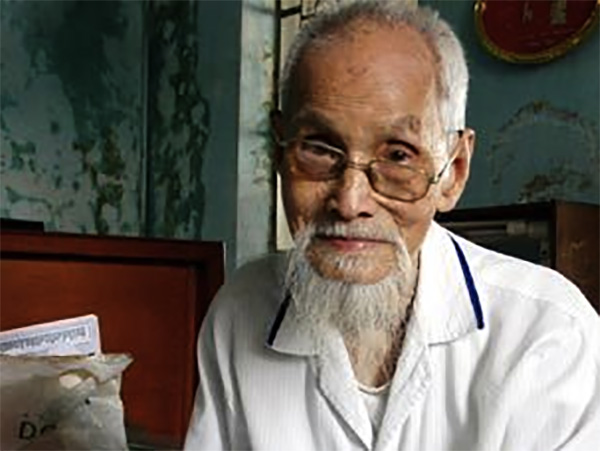

…and in old age.

Thủy asked his friend’s children to photocopy the letters and send us by express mail. I have read them all, many times.

Mr. Nguyễn Thế Đoàn arrived. He was the chief of film-developing technology; only he could be given the film. He is a person I’ll never be able to forget. He was from the South, and was at the forefront of the revolutionary film generation. He was famous for filming the Second Party Congress in Việt Bắc (the Northern warzone controlled by the Viet Minh), and for other scenes showing Hồ Chí Minh visiting workers, meeting farmers, riding a horse on a mission, crossing a stream, walking through jungles, doing martial exercises, playing volleyball, and so on…

There are many interesting and lively tales concerning his filming of these scenes that have never been recounted. These rare and precious materials have been widely used by later generations in all conceivable places, times, and programs, but often without attribution to him. In January, 2009, he was awarded the second class Independence Order of Merit, but this recognition came late and was devoid of the publicity and pomp accorded to other creative artists.

At some point in the 1990s, I went to Vũng Tàu to pay him a visit. The old artist kept gazing out at the ocean for hours without saying a thing…

After I had taken my film back to the north, there were some rumors that my report should not be believed: “What sort of filming did he ever do—he just kept pressing the ‘go’ button to use up all the film, so he could flee back to the North; there are no pictures at all in that film.” In fact nobody believed that I was able to film anything, as my studies had been interrupted and I had no experience, other than pressing the button a couple of times. “…and as for Agfa or ORWO color film, he doesn’t have a clue!”

After discussing all the technical problems with me in detail, and inquiring about the source of the film, Mr. Đoàn said, “Put your mind at rest, and concentrate on your treatment. I’ll do my best to develop the film!”

I didn’t really understand his anxiety. Developing film is a normal procedure in the industry, especially for “masters” like him—so why would he have to “do his best?” Mr. Đoàn took the film back for development testing. I had already marked the segments of the film that could be used for testing.

The first time he tested a twenty-minute segment only, which means he developed it in a bottle, a bowl, or a small vase.

“Thủy! The good news is that the film is very clear, and not mildewed! But the color isn’t appearing,” he announced.

“Please help me. Frankly speaking, if you can’t develop the film, I’ll be dead meat. They don’t believe I’ve shot anything, you know that!”

Mr. Đoàn only gave a hesitant shrug.

There was an order back then that film brought into the war zone could not remain in great 300-meter rolls, but had to be divided and loaded into boxes with 30-meter bobbins, ready to be put into cameras, so as to avoid doing it in humid underground shelters later.

The film that I had shot was Agfa color film, and it was loaded correctly in nice boxes, according to specifications. And that gave them the idea of throwing away the film I had used so as to use the boxes for fresh film to be sent into the war zone!

Mr. Đoàn was extremely upset. He said that many people had told him that “that fellow Thủy” wasn’t capable of filming anything, so he shouldn’t waste his time for nothing trying to develop the film. He came to the hospital and said to me:

“I think there must be something in that film, that’s why I’m determined to develop it. But since the film you shot was Agfa color it has to be developed in a special way. Where on earth did you get this film? We never sent this kind of film to the South, and have never used Agfa color before! We only use ORWO color, and in the war zone, we only shoot black and white—we have never filmed in color!”

I said almost in tears, “How could I know, brother? I went there and did hill farming, then asked for permission to film the war. They gave me a camera and some film, so I just went and shot these war scenes—how could I know anything about Agfa and ORWO?”

Mr. Đoàn explained that Agfa was made in West Germany, and ORWO in East Germany, and that we were able to develop ORWO film only.

…Good grief! And so, after three long years, extending even beyond the Tết Offensive of 1968, running here and there filming scenes amid bombing and shelling, a horror that went on day after day, only now had I learned this absolutely elementary, absolutely crucial fact!

But on second thought, If I had known back then that all the reels of film that I carried on my shoulders as I plunged into the war amid bombings, taking the utmost care with each image and each scene, would later not be able to be developed, would I have had the courage, the recklessness, to record the war at close quarters, as appears in my film, with tanks, infantry soldiers, and even war planes zooming toward my camera lens?

Absolutely not!

Lying in the hospital, I kept reflecting uneasily on what had recently transpired. Back then, after I had finished filming, I had faced death many times—from malaria, hunger, and exhaustion—and was sent back to the North. Though I could scarcely stand or walk, I had managed to keep intact all the boxes of Agfa color negatives, and had been confident that this would be the first color film to come from the 5th Zone.

I felt so bitter!

For three long months Mr. Đoàn wrestled with the bunch of film I had brought back, but he still couldn’t develop it.

The rumors became almost “official”: Trần Văn Thủy is just a con artist; what could he have filmed? When the war got too hot, he just pressed the button to use up the film he had been issued and… “B quay” (ran back to the North). In that period, “B quay” was the most serious offense, and wasting precious film by shooting scenes just to use it up was a crime that would make a prison term almost certain.

It was difficult in those days for people to believe in each other. What could I use as evidence, to make people believe me? That was what made me miserable as I lay there getting blood transfusions and other treatments in the “Việt-Xô” Hospital: How could I prove that I had shot the film for real, that I had done it carefully, and at the expense of the sacrifice, devotion, and even blood, of many people?

One afternoon during visiting hours, Mr. Đoàn came to the hospital to see me. He was the one who understood better than anyone else the dangers I faced if the film I had brought from the war zone couldn’t be developed. He said, “I don’t know why I trust you. I believe that you shot the film for real, but we aren’t able to develop West German Agfa color negatives. I’ve tried every possible method already. I don’t dare hope any more that the film can be turned into a movie, but if I can just get images from it, that will be enough for me to clear your name.”

I was worried and brokenhearted. Throughout that time, even though the hospital gave me medicines and nutritional supplements, I kept getting thinner and couldn’t sleep at night. I feared that if Mr. Đoàn lost his will to help me, my life, like the film, would be ruined.

Mr. Đoàn continued wrestling with it for several weeks, doing further experiments on his own. He came up with a new chemical solution, and even constructed a wooden mechanism to develop the film by hand.

One day he said, “Hey Thủy, we’ll have to resign ourselves to developing the film in black and white only. It will be “inversive development”; in other words, given direct exposure of the images, the positives will appear directly.”

(LTD:) I said to Thủy: “At that point, the critical thing wasn’t purple sunsets, green coconut leaves, red fire, or yellowed grass, but rather black and white—black and white for the sake of clarity; in other words, to show that the fellow Thủy had had shot the film for real, and hadn’t just faked it! Black and white was the crucial thing!”

“Charlie Chaplin “played” with black and white, and Võ An Ninh did the same. This you know better than I do. You should have been reassured.”

Though this is what Mr. Đoàn planned and envisaged, it was still several months after I had returned to the North with my load of film that he actually started developing the first reel.

Only later did I learn that the process called “inversive” involved two exposures to light. The first was exposure while shooting the film. After that it would be processed in some kind of chemical solution, then brought out for a second exposure, after which it was taken into a dark room and processed again in another solution; only then did the “positives” appear.

But, perhaps because Mr. Đoàn’s assistants thought that this material contained no images, or that the images had no value, they did their work sloppily, and didn’t allow enough time for the second exposure, so that the “positives” appeared prematurely. The result was that what should have been black appeared as white, and vice versa; so for example, you would see black skies, white coconut trees, and black airplanes—and aside from that, many scenes were marred by flickering.

(LTD:) I teased Thủy:“There are many artists experimenting with black and white, but with ‘flickering’ like this, Trần Văn Thúy is unique in the world! This must be patented!”

When I met Mr. Đoàn, it was the first time we knew of each other; we were neither close, nor bound by favors, or by any design for reputation or profit. How could he have thrown himself so wholeheartedly into this work, and how could he have been so concerned on my behalf? I saw that, aside from his instinctive sense of responsibility toward his work and toward films born of the blood and fire, the bombs and bullets of war, he also felt a deep sympathy for me because of my years of suffering the deadly horrors of the war zone, and because of my emaciated and sickly condition at the hospital, desperately awaiting his news day by day.

He was the person who believed that “the film had images,” and he understood better than anyone that if he could not develop the negatives, then the “author” of those negatives would be thrown in prison. At that time, I was already subject to irregular treatment, reflecting policies concerning people who had come back from the South. When I departed for the South, my salary had been fifty-two đồng per month. Now, after four or five years spent amid bombs and bullets, and reduced physically to the state of a zombie, my salary was still fifty-two đồng.

All I could do was wait desperately for news from Mr. Đoàn’s developing room.

And then one day, Mr. Đoàn sent me the news:

“Hey Thủy! We have results! Come take a look!”

He had a person meet me at the hospital and take me directly to 42 Yết Kiêu Street, where the Liberation Film Company worked in the campus of the College of Fine Arts. I remember that at this first draft viewing, even Mr. Hà Mậu Nhai, the director of the Liberation Film Company, was present.

Frankly speaking, I was shocked to death when I saw the film. I was immensely indebted to Mr. Đoàn; nevertheless, the quality of the images was very different from what I had imagined when I shot them. Where were the somber purple horizons looming behind the barbed wire of the enemy outposts? Where were the scenes of eggfruit trees burned half-yellow and half-green, the lines of the evergreen willows, and the silvery waves of the rivers?

And these scenes were not my work alone!

There were hundreds of people in the film, but only two of them survived. One is Ms. Văn Thị Xoa in Duy Xuyên District, and another lady in the performance troupe. As for the rest, they are all dead. Mr. Hy, the photojournalist who accompanied me from the beginning is dead. Mr. Tý, who took over from Mr. Hy the job of guiding me around, carrying my film stock, and who went everywhere with me day and night, devoting his life to my film work, who mixed milk with beer for me to drink when I had abdominal pains, is also dead.

All the personages in the film were arranged by anh Tý for me to meet—otherwise, I would have had no idea who was who! Or what was happening where! Thanks to him, I got to know people and their fates, so as to put their living stories into the film. I silently cherished a deep feeling of gratitude toward him, and thought that if the film could be produced, I would surely put his name in the film as its co-author. But in conditions of such hardship and danger, how could I be so sure that it would become a film to speak of this beforehand? So I just kept the idea in my head and prayed to God that the film would survive, and that I would survive! After I returned to the North, my motivation for producing the film consisted partly of my debt to all my friends in the war zone, and especially to Mr. Tý (Triều Phương)…

While I was frustrated and exhausted, Mr. Hà Mậu Nhai was especially enthusiastic. He looked at me with affection in his eyes and encouraged me:

“Let’s edit it. Keep going!”

Later on, he was the one who did everything necessary to contribute to the final success of the film after a long saga.

As for Mr. Đoàn he remained lost in thought and didn’t say a word.

And thus I was rescued from criminal accusations, such as being a “con artist” and a “B quay” (which was equivalent to being a defector). Nevertheless, the images in the film were a disappointment, though only from a technical point of view.

I sat down in the production room, which was also at 42 Yết Kiêu Street in the campus of the College of Fine Arts. At first I rejected all the scenes that had been corrupted by improper development; that is, the ones that looked like negatives, and also the ones that flickered. It was painful, as if a knife were cutting my entrails.

Mr. Đoàn thought about this a good deal, and after a few days said to me, “Thủy—I have a very strange feeling about those “corrupted” scenes that you’ve removed!

I was startled at his observation. After several days and nights of agonized obsession with this problem, compounded by intense feelings of regret, I acted on Mr. Đoàn’s suggestion, trying to incorporate those corrupted scenes in a long sequence of fierce fighting. This made an unexpectedly strong impression. When postproduction was completed, the film appeared in its first prototype.

The first screening was at 22 Hai Bà Trưng Street. Present at the showing were the musician Phan Huỳnh Điểu (the author of some famous songs), Mr. Hà Mậu Nhai, Mr. Khánh Cao, (father of the cinema artist Trà Giang), and other film and arts people from the 5th Zone.

“The People of My Homeland” was shot in the war zone and shown at the 1970 Leipzig Film Festival. The director (me), still thin as a rail, receiving the Silver Dove Award.

When the film was over, everyone was shocked! They couldn’t imagine a film so strange. Nobody would believe it was made by an unknown fellow with no professionalism like me, who didn’t know a thing about film, who had grown corn and manioc in the hills to eat, who wrote his own script, did his own directing, shot his own film, dug underground shelters to hide the film, and carried the film back to the North for the Cinema Department!

Yet it became an actual film! And won an international prize!

Later on, at an international film festival, Mr. Roman Karmen, who at that time was on the panel of judges, asked me, “The scenes that looked like negatives and flickered—did you make them that way intentionally for effect, or was it the result of faulty development?”

I had to tell him the truth. “It was precisely those scenes that produced the deepest impression on the judges,” observed Mr. Karmen.

On that occasion I could never have imagined that two years later I would be a student of Roman Karmen for five years at the National Institute of Cinema in Moscow!

Order In Whose Eyes from the University of Massachusetts Press, or from Amazon.

All text and images are © 2023, Trần Văn Thủy, all rights reserved. Written permission is required for any use.