Chapter Nine

I will continue to relate what happened at the film show at 22 Hai Bà Trưng Street. Everyone was stunned, and then merrily congratulated me. But one person sat in silence without saying a word.

He was Trần Hữu Nghĩa, working in the delegation of National Liberation Front (NLF) at 19 Hai Bà Trưng Street, just on the other side of the street, across no. 22. Nghĩa was a cousin of Triều Phương (son of his uncle). We had known each other for a long time, and I had invited him to come see the film. Only after everyone had left did he speak:

“Anh Thủy, I’m deeply moved at this marvelous film you have made about my homeland, and at your acceptance my homeland as your own in “The People of My Homeland”. When I saw Triều Phương’s [anh Tý’s] name appear next to yours as the co-author of this film, I was in such a pain that I wanted to cry, for he never got to see the film… Triều Phương has just died, you know!”

It was shocked and almost paralyzed. After all the efforts we had made, after all the dangers we had come through, now the time had come to pick the fruit of the trees we had planted, but Triều Phương was no more! Like so many others in my group he had disappeared!

His death anniversary is on the fifth day of the fifth month of the lunar calendar. When he departed this life he left two young and helpless sons, and his wife who was still in prison.

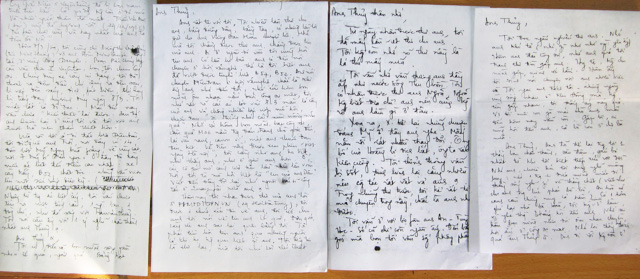

(LTD:) Thủy showed me the letters, deeply laden with human feeling, that anh Tý had sent him from Quảng Đà, and said,

“I was afraid they might be lost, so during my years of study in Russia, 1972–1977, I took those letters with me and kept them carefully…”

In 1988, when I went to a film festival in Dà Nẵng, I visited the grave of anh Tý. He lay next to his younger siblings Sửu and Mão in the Martyrs’ Cemetery of Duy Xuyên District. As we stood before the incense and the spirits of my deceased friend, I gave these letters to anh Tý’s children, so they could keep them as a precious record of the handwriting, feelings, and thoughts of their father in the midst of the war, when they were still only a few years old. A couple of decades had passed and this was the first time in their lives that they got to see their own father’s handwriting, and hear the stories about his life during the war. When they read the letters, they dissolved in tears, especially Cẩm Linh. The TV crew from the Dà Nẵng television station, who accompanied us, didn’t lose this opportunity and they made a film called Returning to a Former Battlefield, a moving documentary, to tell this story.

Thủy asked his friend’s children to photocopy the letters and send us by express mail. I have read them all, many times.

As I’m writing this, artillery from Bồ Bồ and An Hoà positions keeps shelling sporadically, shaking the underground shelters…

Dear Thủy,

I read your letter hungrily. I miss you in a way hard to describe (it’s like what one might feel for a departed lover). The day you were digging the shelter, I missed you so much that I tried to come see you. But Hy was so nasty he wouldn’t let me, I was very upset… My wife raised a hen waiting for your next visit to eat—that hen is still there. When people saw me, they always asked about you, even people in Bà Market. You have left in my heart the image of a sincere friend, to whom I have been most deeply attached since I first started to experience life. As I miss you so much, I often wonder wildly that if one of us died, how the surviving person would think about the dead one (as I’m writing this, artillery from Bồ Bồ and An Hoà positions keeps shelling sporadically, shaking the underground shelters). One day I dropped in to see Mrs. Hảo. I didn’t want to stay long, because I heard little Thắng asking about you. I remember the day we lay there in a secret shelter with an empty stomach, holding each other to share the warmth. That memory is a beautiful experience! But now you’re gone, no longer sharing the fire with us…

My life these days is full of hardship, you know. I’m no longer witty, no longer naughty; there were days I had to run around finding food for the unit. I’m worried that if you see me again later on, I’ll no longer be the same fellow Tý in Xuy Duyên District. I’ve forgotten everything, except you. Yesterday, I stopped over at Sơn’s grave to burn some incense, I felt I’ve become too soft, perhaps too sentimental. Something to love and to remember would enrich one’s life.

Perhaps I miss you more than you miss me.

Whenever I saw anyone coming from the North, I would ask for you. On one occasion, they told me that you had come to talk at the Artists’ Association, thus I learned you had managed to cross the line of fire by B57s and B52s. If you talked about the South at the Artists’ Association, then you must surely remember me and the day we lay holding each other down in a secret shelter. I remember very clearly your green undershirt produced by “March 8” textile factory, now full of patches to cover the torn spots and filled with the smell of sweat and gunpowder. “Oh how I remember that warm and salty smell”. I also remember the day we popped out of a small underground shelter, holding a M26 grenade and laying in the midst of the tall grass, with faces blackened by gunpowder. After coming up here, I saw the film A Day in Hanoi, which made me remember you even more intensely, as if I were seeing you, getting closer to you. Oh, the girl who opens the window and gazes up at the sky (in the film) made me curious to ask around, and I later learned that she was Dân’s younger sister! And by now, I also remember the doctor who came to work in Quang Ngãi!

Through all the intense years of the war, I have never found such feeling, such friendship, such camaraderie, as I experienced when living with Trần Văn Thủy. I say this with the utmost sincerity, my dear friend!

Will you be returning to the South? Now that you’re gone, I have realized how the “Hanoian” quickly adapted to the hardship and ferocity of life in this arch of firepower. That quality itself had left a deep impression on me. Those days of bitterness and hardship had brought us together and made us strongly attached to each other.

Dear Thủy, my wife was still in prison and she must have thought of you quietly, and that is very easy to understand. I’ve noticed many times that she has written letters to you, very sincere letters that in some places have an air of a sister. Perhaps for that reason, she has written but not sent them. While remembering you, I often sing songs that you often sang. How is your illness these days? Has the film you made been sent abroad to be developed yet? Are you satisfied with it?

To this day, I still dream of A Day in Hanoi—nothing would make me happier than for you to show me around the streets of the city, though I would be “a bewildered golden deer treading on the withered yellow leaves.”1 Oh Thủy, I’ve been carried away…

(LTD:) Those letters from anh Tý were full of such emotion. But, should we have quoted them all here? Although I am not Thủy, I feel I have a lump in my throat when I read them.

I remember in the middle of the 1960s, when the “Letters From the Front Line” were published, I read them but never had such feelings as when I read anh Tý’s letters. Probably it was because the Front Line Letters were printed words edited for a book, so they were no longer original handwritten letters sent directly from the front line.

No commentary is necessary for letters written from the heart, in the midst of the smoke and flame of war…

| 1. | This is an allusion to a famous poem by Lưu Trọng Lư. |

Order In Whose Eyes from the University of Massachusetts Press, or from Amazon.

All text and images are © 2023, Trần Văn Thủy, all rights reserved. Written permission is required for any use.