Chapter Ten

And so, thanks to the protection and assistance of Mr. Đoàn, and thanks to the interest of a number of elder, responsible officials, The People of My Homeland was produced and won the Silver Dove Award at the Leipzig International Film Festival in 1970. Many copies of it were made and shown around in many places, including the war zone; and then it won the Silver Lotus Award in a national film festival.

From that time on, I felt that everyone looked at me with eyes more friendly, more kindly disposed, than before. I was kept in the North, partly because of my poor physical condition, which would have made it hard for me to survive in the war zone as I had done previously, and also because the Film School needed somebody with experience filming in combat conditions to be the principal lecturer in the next training class for cinema photographers to be sent to the South.

Most of the students in the class I was put in charge of were originally from the South, and had been regrouped to the North. The rest were students from the North, or people assigned by various other departments. Many of them became very successful later on.

When I took over as principal lecturer of this class, I was still very thin and weak, and had little that I could contribute. But, given my own experience of filming the war as a cinema photographer, I tried to help the students visualize and adapt to the harsh future that awaited them.

The director of the school was still the kind and virtuous Trần Đức Hinh, and the manager of curricular affairs was still the fun-loving Trương Huy, while the school administration manager was Mr. Sáng, who came from the South. He was extremely dedicated to the task of providing meals and lodging for the students. The physical infrastructure of the Film School back then consisted merely of a few rows of thatch-roofed houses set around an earthen field at 33 Hoàng Hoa Thám Street.

Around the middle of the year 1972, Mr. Hinh let me know that the School Board intended to give me further training as a film director by sending me to a course of study in the Soviet Union. I was very glad, but also undecided as to whether I should go or stay. I had been far from my family for more than ten years, including five years in the Northwest, and five years in the South. My parents were old and my younger siblings still had no certain future. My wife had just given birth a few months previously to our first son, Trần Nhật Thăng. We lived from hand to mouth, and had to go out to evacuation points day in and day out.

But the upshot was that I had to go—go so as to find a way forward, and to find a way to rescue my family, as my wife observed to me when we parted at Lập Thạch in Vĩnh Phú1

Now as I look back on those days, I cannot but express gratitude to my family and my wife, who gritted their teeth and accepted every hardship in the years that followed, so that I could feel at ease about going away again for a few years. My father was even quite encouraged at the news, not because I had accomplished anything, but perhaps because this somewhat lessened his obsession with “background-ology” in his mind.

Due to the American bombing raids going on that year, students going to the Soviet Union had to regroup at Đại Từ in Thái Nguyên. Most of them were new public high school graduates, but there were also some older students who had gone on missions like me, and others as well. Ca Lê Thuần was made chief of the group, while I was made deputy chief.

While waiting for the train and dodging American bombs at Đồng Đăng (a town near the Chinese border), the chief and his deputy (me) went out to drink on the sly and, having gotten drunk, went staggering around on the pebbly riverbank exchanging ribald jokes, and pledging to preserve our memories of that day forever.

Whoever has gone on the train journey from Hanoi to Beijing, to Ulan Bator, and then to Moscow will never be able to forget that ten-day, nine-night journey. Nowadays, going by airplane is certainly more convenient, but if you want to appreciate the surroundings as you travel, then the train trip is best. This train journey introduced us to many different scenes, cities, villages, fields, rivers, complexions, and languages. One impression I’ll never forget was of Lake Baikal, as our train ran along its banks. It is called a lake, but it is as huge and endless as an ocean. On a map, Lake Baikal looks like a grain of rice, but the train had to travel half a day before it could pass one sharp end of that grain of rice. Everyone craned their necks so as to gaze out the windows and feel the boundlessness of creation…

Then there were the rows of poplars—no, forests of poplars to be precise, one following on another in endless succession…

It is not just for its entrancing beauty that I remember Lake Baikal. The place left further deep impressions on me when, during my second year of study at the National Pan-Soviet Institute of Cinema (or Всёсоюзный Государствениый Институт Киноматографии, abbreviated as ВГИК or, in English, VGIK), I returned there to make a film about the building of a railroad line that would connect the Amur River with Lake Baikal. Known as the “Baikal-Amur Mainline” in English, it was called “БАМ,” in Russian, an abbreviation for “Баикало-Амурская Магистраль.” Though it was only a training exercise, the film won me many favors, which I shall detail later, since it concerns my professional development.

In 1972 and 1973, I studied Russian together with the other international students at Lomonosov University. That was the first time I had seen such an enormous university. In the summer of 1973 I went to VGIK to take my qualifying examinations according to school regulations.

Here, to my extreme astonishment and joy, I met Roman Karmen again.

He was sitting in an elegant armchair in the middle of a room, surrounded by professors and department chiefs. I sat across from him, and sitting with me, ready to help me out if I ran into language problems, was Mr. Nguyễn Mạnh Lân, a close friend of mine who had gone to Moscow three or four years earlier, and was fluent in Russian.

Karmen looked at me laughingly and narrowed his eyes.

“Ooh-la-la! Дравствуй студент-лауреат (Welcome to the prize-winning student)!”

He asked me if I had gotten married and had children yet. And how did I think the war in Vietnam would develop? Were Mr. Mai Lộc and Mr. Phạm Văn Khoa in good health? Karmen was full of memories from 1953 and 54, when he did some filming in Vietnam… And he got carried away as he chatted expansively—what he said had nothing to do with a formal interview. The other professors sitting nearby looked impatient, but Karmen paid no attention.

“What year in the curriculum would you like to study?” he asked.

Like a rebounding spring I answered, “I’d like to learn from you sir, and start from the first year like everyone else.”

“Then from now on, you can regard yourself as a first-year student.”

There was some whispering. One professor raised his voice: “Wait a minute, we mustn’t proceed so quickly and simply.”

Karmen turned around and shrugged his shoulders: “This young man won a prize at an international film festival three years ago, in 1970, where I was among the judges. If you gentlmen could see that film, you would have the same opinion that I have. This young man filmed many scenes at the risk of his life. As far as I’m concerned, the fact that he is alive and sitting with us today is in itself a miracle.”

Mr. Nguyễn Mạnh Lân witnessed this, and heard clearly everything that Karmen said. Thus it appeared that I would not have to take any qualifying examinations. My life has at times had such moments of luck; eight years previously, when I entered the film school in Vietnam, I also didn’t have to take a qualifying exam; Mr. Nông Ích Đạt reasoned with the school director Trần Đức Hinh, saying that I must be given special treatment because I came from the mountainous region…

Two episodes in my learning curve. The first time, this young fellow who was “ethnic,” but not a Lò, a Nông, or a Ma, had gone down to the lowlands to study at the Hanoi Cinema School without taking an entrance examination. The second time, this “country fellow from Hanoi” went all the way to the Soviet Union, the land that had produced all those “Soviet wide-screen color films” that had been shown in every corner of Vietnam, in order to be a university student. And again, without taking any examination!

Then from now on, you can regard yourself as a first-year student.

From the first through the fourth year, we got to study all aspects of the theory and practice of making films. The fifth year was reserved for making a (well-funded) “graduation film.” In the last year, the students were almost totally dispersed, and everyone was concerned with preparing for the examinations, and writing theses, so very few came to the lectures as scheduled. Professor Karmen, too, rarely came to class, because he had his own work to attend to, traveling everywhere in the world.

I spoke to him: “Professor, I’d like to go back to Vietnam early.”

“Why not remain here, so you can continue working on your advanced degree?”

“No sir!”

I felt that, having studied all aspects of the profession, my job was now to make good films—what good would it do to hold an advanced degree if I made bad films? My purpose in studying was to pursue a profession, not to gain an advanced degree.

“Professor, Please give me permission to defend my graduation early. If I remain here for another year, too much time will be lost.”

“All right. Use the film The Place Where We Lived (“Там Где Мы Жили”) as your graduation film, okay?”

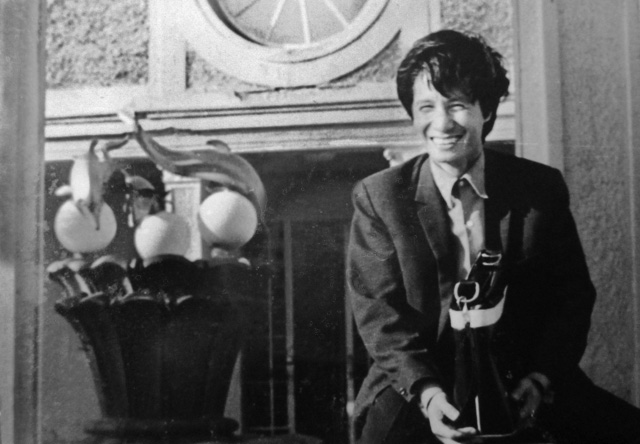

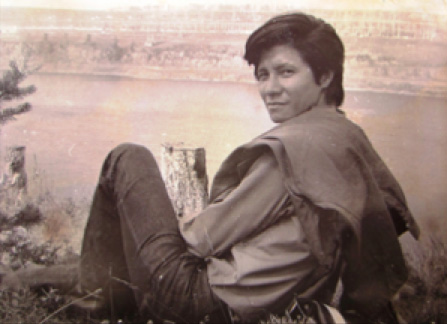

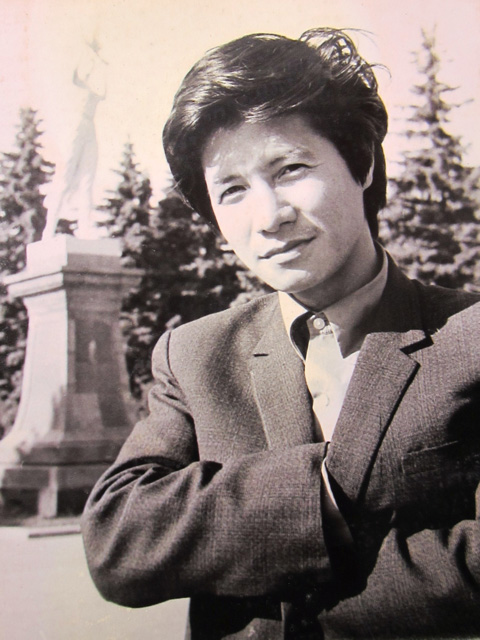

In Siberia—choosing a scene for the film “The Place Where We Lived”.

That was a film that I had made at the end of my second year. It was a documentary about the life and work of the international students on the construction site for the Baikal-Amur railway line in Siberia. As soon as that film was produced, it won the Red Carnation Award, that is, the highest prize offered in the VGIK film festival, and was entered in a competition in Poland, where it was shown in many places. I used that film to defend my graduation, and received a “red diploma” before I returned to Vietnam one year earlier than scheduled. Thus I was in Russia only from 1972 to 1977.

Later, that film turned into a “classic”; it was shown every year to all the first-year student directors. The Vietnamese students were very proud of that success. But actually it was only a normal film, a “добрый фильм” (“a not-bad film,” good enough to watch); the teachers and students spoke well of it just to encourage me.

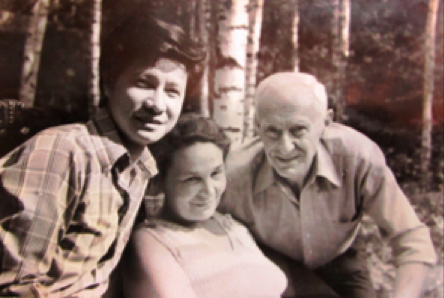

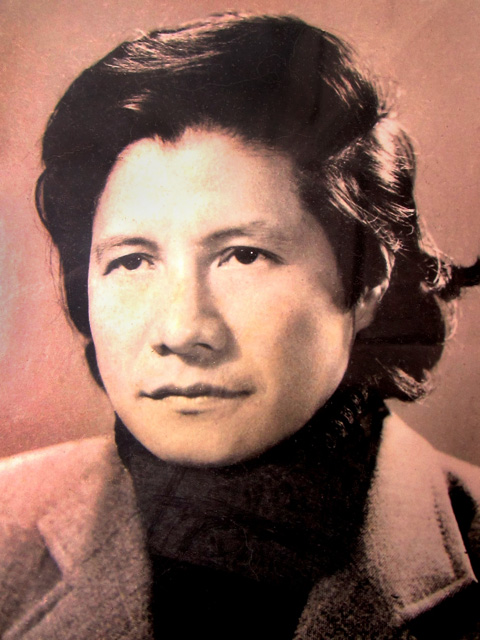

Me with Mrs. Garivovna, an associate lecturer, and Roman Karmen.

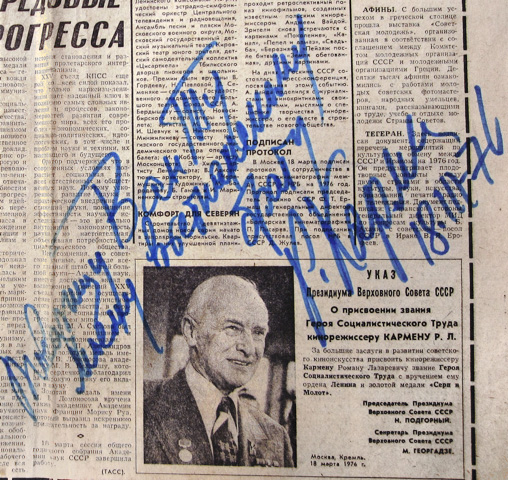

That I got an opportunity to learn from Roman Karmen was a great stroke of luck for me. During my years of study with him, I was the recipient of many favors from him, of which the foremost was that he trusted me and didn’t demand too much from me. And on March 3, 1976, he was awarded a major prize by the Soviet government. When he came to class after that, he brought along a copy of the paper Soviet Culture (Советская Культура), which carried this news along with his photograph. The students excitedly congratulated him, and each one of them wanted their teacher to give them the paper with a handwritten inscription. He said, “There are seventeen of you, and I have only one copy of this paper. I can give it to one person only.” Narrowing his eyes, he gazed around the room at his students from Uzbekistan, the Sudan, Palestine, Kirghistan, Karkaz, Poland…

Thủy comes from the greatest distance—so let’s agree to let Thủy keep this paper as a souvenir when he returns to Vietnam.

His gaze stopped when it fell on me, and he said “Among us all, Thủy comes from the greatest distance—so let’s agree to let Thủy keep this paper as a souvenir when he returns to Vietnam.” He opened a black marker pen and wrote across the page next to his photograph, “To Trần Văn Thủy, my younger brother from Vietnam.”

When I went to visit him in his garden retreat in a suburb, he talked with me about Điện Biên Phủ, and about the book, Light in the Jungles (Свет в джунглях) that he had written after leaving Vietnam. I think it’s a pity that when you mention his name in Vietnam, many people are aware only of the film Vietnam on the Road to Victory—in the Vietnamese edition, the narrative in the soundtrack written by Nguyễn Đình Thi (In the Russian edition the narrative was written by Karmen, and the film was entitled simply Vietnam).

Few people know of this excellent book about Vietnam that Mr. Karmen wrote in that period. Even the film he made is hardly known at all to the younger generation in Vietnam. I heard that a few years ago some staff members from Vietnam Television (VTV) went to Moscow and “discovered” this film, whereupon they spent a sizable sum of money to buy the copyright to it. If they didn’t know, they should have asked: The copyright to the film Vietnam on the Road to Victory (in other words, the film Vietnam mentioned above) belongs to us (meaning both the Soviet Union and Vietnam, naturally). Who on earth would spend money to purchase a copyright that they already owned and then broadcast the film on TV as a “discovery,” a brilliant “coup,” and even add to it the subtitle, “Copyright belongs to Vietnam Television?”

What do the elder Vietnamese filmmakers of the Palm Hills (Đồi Cọ) generation who used to work with Karmen producing the film Vietnam on the Road to Victory think of this? Having made such a blunder, Vietnam Television Station should have apologized to the Government for having spent money for a mistaken reason and secondly to the Vietnam Cinema industry for having done something so foolish and useless.

The garden retreats of Karmen, Simonov, and Yevtushenko lay next to each other in a suburb north of Moscow. We students used to gather there, and sometimes had opportunities to converse with famous personages of that era. Mr. Simonov never in his life had any knowledge of film-making, but after the publication of his collection of poems, Pain That Belongs to No One in Particular, which spoke of Vietnamese children in the midst of war, and after the director Marian Babak made a film with the same title, Simonov was regarded as its chief author.

In making such films, there are “behind the scenes tales,” and professional tales. Film theoreticians and instructors all teach that a film’s script mustn’t be written until the images have been edited in post-production. But in this case, the commentaries and poems for the film came first; then Marian Babak went to Vietnam to gather images to put in afterward. The conceptual framework of documentary filmmaking can be broken as long as two criteria are met: truthfulness and excellence. For this reason, when I make documentary films I often have written the narrative first, though when editing the images I sometimes had to make further adjustments.

During my time in the Soviet Union, I got to study a wide array of subjects related to cinema and social science. My knowledge was greatly broadened. However, one drawback was that I was almost at a loss every time my Russian friends would discuss social topics in my presence. They often said to each other, “He doesn’t understand a thing.”

And I must truthfully confess that though I lived right in the capital of the Soviet Union, I had no deep understanding of Soviet society at that time; I saw only the tips of floating icebergs. I knew nothing of Solzhenitsyn, Pasternak, or Sakharov; I knew nothing of Trotsky, etc. When I watched Soviet movies, I always believed that the Red Army would win and that the White Army would lose…

I had no deep understanding of Soviet society at that time; I saw only the tips of floating icebergs.

Both the Cinema Institute (VGIK) and the dormitory where we lived were close to the National Economics Exhibition, called VDNH (“ВДНХ”) in Russian for short. For a time, a slogan was hung there in bronze letters as tall as a person, which said “The Communist Party of the Soviet Union solemnly pledges to the present generation that ‘We will live according to the principles of communism.’”

The fact is that at that time we all loved Russia and the Russians enormously, but had little understanding of what Russian and Soviet intellectuals were thinking. It was only later on that I gradually came to understand that they didn’t approve of many concepts held by the authorities, and that they were dissatisfied with the regime…

That a humble person like me, coming from such a poor background, was now being given a chance to go overseas and study in a place like this was indeed a huge favor from the heavens.

I still remember the graduation ceremony that day, because there were two students of famous professors who were there for the defense: One was nick-named “Cross-eyes,” an Algerian friend, a student of Gheraximov (later the name of the institute would be changed to “Gheraximov”), and me, a student of Roman Karmen.

On receiving my diploma I got on a train and returned to my country at once. That was late in 1977.

On receiving my diploma, I got on a train and returned to my country at once. That was late in 1977. I had the good luck to be the only student in my class to graduate in the presence of our dear teacher. My classmates graduated in August, September, and October of 1978. By that time, Roman was no longer with us. He was born in November, 1906 and died in May 1978 at the age of seventy-two. In his hometown of Odessa there is a street that bears the name “Roman Karmen.”

I remember that during my graduation ceremony in Moscow, my teacher asked me,

“What will you do when you get back to your country—what topics are you concerned about?”

Politely, I said, “Sir, Vietnam, is now at peace; there will never again be war—no enemy will dare touch our country again, as our party chief Lê Duẩn has said. Therefore, the topics that concern me are human destiny and the building of a better society.”

But just when I got back to Vietnam, troubles were erupting along the Sino-Vietnamese border, followed by the “Nạn kiều” event (Chinese nationals leaving Vietnam), and then by a bloody war that devastated most of the six border provinces. To discuss this war would require much paper and ink, much time, and much honesty. How could we have tolerated the Chinese People’s Liberation Army troops pouring into our territory wearing Vietnamese army uniforms, burning houses and butchering local people before the shocked eyes of the horrified inhabitants? At that time, all the film companies from the North to the South, including the Army Film Studio, the Feature Film Studio and of course our Documentary Film Studio rushed to send crews to the border region to make films on this topic.

Having just returned, I followed current events from March 1978 on, when Mr. Xuân Thủy (former chief negotiator for the Paris Peace Accords) went on the air to answer questions posed by foreign reporters concerning the border problems with China. I had a hunch that war would certainly break out. Once, talking with Mr. Lý Thái Bảo, director of the Documentary Film Studio at that time, I commented to him half in jest as follows:

“Now that war is about to break out at any time, if you chaps keep making films about the “Nạn kiều” problem, the “Bắc Luân” bridge incident, or other nonsense stories, we’ll all be sent to perdition…”

Mr. Lý Thái Bảo nodded in silence. A few days later he met me again and said, “I’ve discussed this with the Board of Directors and the Council of Artists—everyone agreed with you but had no idea how to make sense of this and keep pace with events.

Then he chuckled, “Okay, since you were the one who made the point, you should do it yourself—that’s the best option.”

I was startled. The regular practice in the profession is that, when you join a film-making company, you’re supposed to go through a period of internship, assisting your senior directors in making a few films; only after two or three years are you considered ready to be an independent director.

But since Mr. Lý Thái Bảo had given me this assignment, I had no choice but to start at once making my first film for the studio. I searched around for documents to read, wrote a film script, and went up to the border to investigate the actual situation. I directed the film, organized the shooting, and wrote the narrative. Phạm Quang Phúc, my younger brother-in-law, was the principal cameraman.

The name of the film was Betrayal (Phản Bội). A short while afterward, the film made a sudden splash and won a Golden award for “best director” in a national film festival in 1980. It was a 35-millimeter film, the longest in the history of the Documentary Film Studio of Vietnam: 90 minutes.

Documentary films are often difficult to make and difficult to watch, but Betrayal was as attractive as a good feature film, full of witty narrative and dramatic images. This attracted much attention, both within Vietnam and in other countries, such as Sweden, and at film festivals in Tashkent and Leipzig. In particular, Hainowski and Soloman (two sharp-minded German film makers who directed Pilots in Pajamas) set a high value on this film. Perhaps that’s why in my film career, I have had no opportunity to enjoy the privilege of “cắp tráp” (to play a supporting role), assisting other senior directors. I have neither suffered nor enjoyed the influence of anyone. I did whatever came to my mind that seemed good.

These days people no longer show this film and don’t want to mention it either, for sensitive reasons, both legitimate and illegitimate, within the political arena. If I had a chance to redo the film Betrayal, I would restructure it and rewrite the narrative. And the new title might be “The Sorrow of a Small and Weak Nation.”

| 1. | Lập Thạch was the evacuation destination for several offices under the Ministry of Culture. |

Order In Whose Eyes from the University of Massachusetts Press, or from Amazon.

All text and images are © 2023, Trần Văn Thủy, all rights reserved. Written permission is required for any use.