Chapter Thirteen

Script of The Story of Kindness

While being watched by the police, and while dealing with troubles related to the saga of Hanoi In Whose Eyes, I got into even more hot water by making The Story of Kindness, a far more direct and outspoken film, not delicately suggestive like Hanoi In Whose Eyes. Only the protection of the gods could help me get away with an “offense” like that.

This film faced no less hardship and trouble than its elder brother, Hanoi in Whose Eyes. Born later, it was more nimble and adroit, but suffered even greater torment. The story of this film’s creation is also full of mysteries and tales worthy of thoughtful consideration.

Books and journals have spoken a great deal about The Story of Kindness and about what goes on in it—but what are the features of the film itself that gave rise to all this noisy discussion? Not everyone has seen it, and not everyone has the time to view it again. Therefore, let us go over the film again through the words in the script. These amount to only half the film, but they contain its soul.

The Story of Kindness’s Filmscript:

While being watched by the police, and while dealing with troubles related to the saga of Hanoi In Whose Eyes, Trần Văn Thủy had the guts to make the film “The Story of Kindness”.

Reel 1:

(An open book, with a goose-quill pen)

Once when I was arguing about film-making with a friend, he grew irritated and scolded me, using words that I found strange:

(a sheet with written words)

“Of course, only animals could turn away from human suffering, and busy themselves looking after their own skins.”

(the goose-quill pen)

The words seemed so emotional and bold—I suspected my friend had borrowed them from somewhere.

(the film title)

The Story of Kindness

(the names of the filmmakers appear over background images)

The editor of this film told us that for ages past, our elders have taught:

“Decency exists in every human being, in every household, in every lineage, and in every nation. Let us be persistent in awakening this quality; let us place it on our ancestral altars and national podiums. For without this, even the greatest effort and best vision of a people will be futile.

Let us first of all lead our children, and our adults as well, in learning how to be human beings—decent human beings—before hoping to turn them into people of power, ability, or distinction.”

(people visiting graves)

Today, the twentieth of the fourth lunar month, is the death anniversary of a colleague of ours. We don’t know why, but most of our friends who have died over the past few years, were taken by the same fatal illness: cancer. These include the cameramen Nguyễn Quý Nghĩ, and Nguyễn Quang Trình, the script writer Quang Minh, the film director Tô Cương, the cameraman Phan Trọng Quỳ, the directors Trần Thịnh and Xuân Thành, and now Đồng Xuân Thuyết as well.

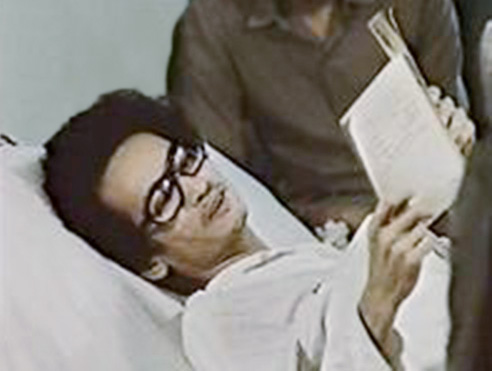

We followed Thuyết’s illness for two years before he passed away. In his final hours, he calmly spoke to us as follows:

(Thuyết speaking with his friends)

I’ve been reading this book—I think it’s wonderful… Listen to this paragraph!

“In the past several days, my body has been racked with pain, but in moments of respite, I’ve been reading this book—I think it’s wonderful. Listen to this paragraph!”

“…A man’s spirit is a hundred times heavier than the body, so heavy that one man alone cannot carry it. For that reason, we must try to help each other, while we are still alive, so that our spirits may become immortal. You help my spirit towards immortality, and I help another, who then helps yet another person, and so on without end… so that the death of man will not leave us in solitude…’ Isn’t it extraordinary?”

(Thuyết’s coffin being carried by his friends—Thuyết’s voiceover at his own funeral)

“…A man’s spirit is a hundred times heavier than the body, so heavy that one man alone cannot carry it. For that reason, we must try to help each other, while we are still alive, so that our spirits may become immortal. You help my spirit towards immortality, and I help another, who then helps yet another person, and so on without end… so that the death of man will not leave us in solitude…”

(Thuyết talking with his friends)

- If I survive, I’ll be as happy as if I were celebrating a festival. But if I’m unlucky… there’ll be nothing much to regret—because while still alive, we’ve lived with one another quite decently, haven’t we?

- But if you should be… unlucky, do you have any “last wishes?”

- As for “last wishes”, I fear you are too busy—you’d forget them all. But for the past few days I’ve been thinking that you all should do something together—something inspired by human love, or something about human suffering, for example.

- That’s difficult!

- Maybe so, but you still have to do it. If you all turn out to be good-for-nothings, I will have gone first, and I’ll drag you down with me!

(a view of the sky. Thuyết’s words occur again as a voiceover.)

“…There’ll be nothing much to regret— because while still alive, we’ve lived with one another quite decently, haven’t we? For the past few days I’ve been thinking that you all should do something together—something inspired by human love, or something about human suffering, for example.”

Nothing is more sincere than the words of a dying man.

(the film crew shooting scenes at a brick kiln.)

From that time on, we resolved to make a film together about decency—even if only decency in a relative sense.

But our project almost failed, because one day, an enraged brick maker, we’re not sure for what reason, came rushing out and rudely shooed us away:

Do us a favor and get out of here! No more shooting around my kiln!

“… Do us a favor and get out of here! No more shooting around my kiln! We’re sick of you filmmakers. If you dare, then film our real lives. Aren’t you ashamed at the way you keep telling lies? Aren’t you ashamed?”

(The film crew leaving—sound of dogs barking.)

Dear Mr brick maker! Yes, we’re ashamed sometimes. Our elders had a saying: “The most degraded of all professions is that of literature,” meaning that literature and art were the least worthy, the most cowardly and insignificant, of all pursuits.

Oh yes! Our profession is indeed cowardly and mean. It is cowardly, because, though we have many thoughts, we dare not express them; and it is mean, because nobody needs what we make.

How could you be aware, Mr. Brick Maker, that for a long time, we have fallen into the incurable habit of hoping only to satisfy our superiors. A book, a play, a film, will come before the public, but there will be little in it pertinent to life, and little that corresponds to the desires of poor people like you. Instead, we wait for the approval from our superiors.

(the sun, and a bamboo)

If our superiors are pleased, then all is well; if they are displeased, then we must discard what we have done.

If our superiors approve, we are happy,…

(the film crew)

If our superiors disapprove, we are sad.

Even the story of how the cameramen of this film started his profession, though a bit old, is an interesting case in point.

(ducks swimming)

When he was a teenager, living in the countryside, looking after a herd of ducks—not an inspiring job—he was overcome by drowsiness one hot summer day, and crawled into an empty thatched hut to sleep, whereupon the undisciplined ducks invaded a cooperative rice field…

(a personal file being opened)

The village committee leaders were very angry, and at once made a notation of this event in his personal file. Next to the signatures of four committee members, notarized by the district, was a stamp: “Top Secret.”

(the film crew)

And so, for years after that, the poor boy took countless entrance exams, but couldn’t enroll in any school or apply for any job that appealed to him. Finally, by pure chance, he took an exam to enter a training course for cameramen, and was admitted. Thus the duck-herding profession and our film-making profession are only an inch apart.

Reel 2:

(the brick kiln)

“…Do us a favor and get out of here! No more shooting around my kiln!…”

The brick maker who shooed us away was surely in the wrong—we were, after all, public servants.

(a young woman with two children)

“…If you dare, then film our real lives. Aren’t you ashamed at the way you keep telling lies?”

(a man with glasses and a young child)

It seems that he had his reasons though. Even children once laughed in our faces and said, “Ah! When you make this sort of film, we children would get sleepy if we watch it!”

(scene from a documentary film)

Not exactly! We have made hundreds of films: about how people fought heroically, how people work resolutely, and how people believe enthusiastically… these films have gone down in history of an era, giving us glory.

(a poor fisherman)

But we must admit that there are few if any films about what the people eat, or how the people live, or how the people get around, and especially what the people think and talk about.

(a country market)

“Nhân dân!” (“the people”). A truly sacred expression! That’s why it appears everywhere you look! Culturally, there are “People’s Artists,” “People’s Bookshops,” “People’s Teachers,” “People’s Theaters,” and “People’s Daily Newspapers.” And for government institutions there are “People’s Councils,” “People’s Committees,” “People’s Tribunals,” “People’s Prosecutor’s Offices,” “People’s Police,” and “the People’s Army…”

(marching soldiers)

For a time, we had stirring songs about “Nhân Dân” (the People): “For the People, let’s forget ourselves. For the People, let’s sacrifice ourselves Many slogans were instilled in the minds of a generation: “Serve the people,” “servants of the people.” and even “be filial to the people…”

(a soldier)

- Being loyal to the party and the country is understandable, but what does it mean to be “filial to the people?”

- I have to think a little about this—but why are you asking me?”

(a grandfather and grandson)

Let’s take an example, being filial to your father. You look after your father in his old age, care for him when he’s sick, venerate him after his death, and continue to fulfill his unfinished wishes and ambitions.

(an old tea vendor couple)

Filial piety must be coupled with Kindness. You can’t push your parents into the streets to beg for food and still claim that you’re a filial and devoted child.

(a crowd pushing their way into train station)

As for being filial to the People, this expression’s meaning and origin are even more profound..

(a limousine)

Mr. Hồ Chi Minh taught us, “Whatever position you hold, and whatever job you do, you are always a servant of the People. The food we eat, the clothes we wear, the things we use, all come from the sweat and tears of the People. Therefore, we must make them a worthy recompense.”

(the train station crowd again)

Persons of good conscience should be aware that People are not always fairly compensated… Perhaps that’s why the brickmaker, treated us—government employees—in a manner that was neither warm nor decent.

(a young man)

“Hello. What do you understand by decency?”

“I give up. What decency is… that’s difficult to say these days.”

(a young woman)

“What do you think?”

“Can I tell the truth?”

“Yes, go ahead.”

“Yes, yes… A decent person these days is someone I can turn to for help in terms of power or material. The word ‘decency’ has an old-fashioned ring to it. Now, very few people have time to talk about such distant things.”

(a man and a child)

“There are many decent people around us. They’re the ones who love their fellows, who work for the wellbeing of people in society, not for position or possessions. The poor, the lonely, the underprivileged, and especially honest people, are always interested in decency—more than anyone else.”

(a young man in a truck)

“That’s a crazy question. Decency? Let’s think about it: When someone seeking help meets someone ready to give something away, then there’s decency. When someone in trouble meets a man seeking fame as part of a larger design, then again we have decency. It’s a subtle thing, this giving and receiving.

(an old man)

“My dear film makers, the word Tử Tế (decency) has its origin in Chinese. ‘Tử’ means the smallest element. ‘Tế’ refers to the subtlest matters. These two words combined mean that we have to pay attention to the smallest details. The meaning of the word tử tế has doubtless evolved through history.

Tử tế or decency in its full sense cannot be bought, and can’t be acquired just because you want it. It comes to us through teaching and learning, through practice, inheritance and preservation. It is a beautiful and fragrant flower that can’t be dispensed with in this life.

(a young woman)

“Living with each other in tử tế (decency), is a common affair; it’s the consolation of life. Only lepers live without it.

(seaside—a leper sitting alone)

Lepers!

Don’t mix with lepers.

As ugly as a leper.

As dirty as a leper.

As lazy as a leper.

(the sky)

Seeking to understand how the people whom the world calls “lepers” live among themselves, we came across a few cases that seemed to us well worth recounting.

(a grandmother and grandchild)

The child’s name was Tú Anh. But his grandmother said, “Tú Anh sounds like a city boy’s name, but we’re country folk. Your father’s name is Chiền, so I’ll call you “Little Chiền.” Chiền had very few friends, because it was rumored in the whole neighborhood that his mother was a leper. And as she was a leper, her husband abandoned her. The boy’s mother, Mrs Nguyễn Thị Hằng, had to leave the village and wander about begging. But she returned secretly at night to give her son any coins or rice she managed to find. Her physical pain and, above all, her shame had made her decide to commit suicide.

(the child)

She came secretly to the village every night and, with her crippled and twisted hands, she made eighteen thousand bricks.

But what about Little Chiền? He had to have a house before his mother passed away.

(scenes in negative exposure)

So she came secretly to the village every night and, with her crippled and twisted hands, she made eighteen thousand bricks. All you decent and healthy people! Eighteen thousand bricks! Can you conceive of it? Eighteen thousand bricks, the long nights, the chilling wind, the pain and sorrow…

As the house was taking shape, Little Chiền’s mother, a leper with a poetic, dreamy soul, decided to make some humble verses to set down her thoughts for her little son.

Reel 3:

The book this leper kept contained photos and poems of Alexander Bloch, as well as her own poems, written in uneven letters by her crippled hand.

“The flimsy hut shivers in an icy wind,

The poor cradle shakes in the winter’s night.

Your father left without a word.

Is there no one to take care of my little son?

Poor Tú Anh, such a bright name.

My little bird, my little orphan.

I decided I must try to live for you.

For you I must try to build a pretty house.

For you I must brave all weathers,

Brave the cold of wintry, lonely nights.”

(the mother and son)

But the Creator is always fair in his arrangements—the poor woman was treated by devoted doctors and finally recovered. Often, as she walked with her son along the Trà Lý River, she would shed tears when she recalled the names of those doctors.

(a doctor)

“My colleagues and I have often reflected that, though most of our lives have been devoted to medicine, it has taken us a very long time to learn that to understand the suffering of others is not an easy thing.”

(an automobile in motion)

For more stories about these sick people whom the world calls lepers, we went to the Quy Hoà leprosarium.

(a group of doctors)

Here we met many doctors whom we asked, “Dear doctors, which people are the most devoted in the care they give the lepers?”

“The nuns. Without a doubt, the nuns.”

All the doctors responded in the same way, including the ones who had spent all their working lives there, from graduation until their first gray hairs,

(two nuns walking in a forest, holding flowers)

The oldest nuns remembered Hàn Mặc Tử, the famous pre-war poet who became a leper and died here nearly half a century ago.

In speaking of his times, they mentioned two things that struck them. First of all, people back then, due to their ignorance, were very cruel toward lepers.

(a tombstone)

But secondly, when Hàn caught leprosy, many people from near and far spent a lot of money and went to great lengths to care for him. But what was particularly noteworthy was that most of these people concealed their names, so that the poet wouldn’t have to thank them. So we can see that even in Hàn’s times, some people were very decent to each other.

(scenes of sisters caring for lepers)

When we came across the nuns, we were immediately reminded of the Hippocratic oath. “I promise to abide strictly by the rules of noble behavior and integrity in following my profession. I will care benevolently for those in need, and will not demand excessive fees. In respecting this oath, I seek nothing but the esteem of others.

(a placard bearing the oath)

The Hippocratic oath is a decent oath.

Since ancient times, men have looked for truthful words with which to frame oaths in the name of faith and suffering and the human spirit, avoiding words that are full of vanity.

(a sister helping a handicapped person)

We asked, “Sisters, what brought you to serve the lepers with such serenity and devotion?”

“The place we all start from is our faith.”

Yes people cannot live together without faith. And from ancient faith in the supernatural and faith in religion, people have progressed to faith based on evidence: faith in that which truly exists!

(ocean waves)

Faith is a natural and powerful thing.

Faith cannot be borrowed, imposed, or taken away by force.

When one loses faith, one loses everything.

(a leper tugging at a net on the ocean)

The greatest tragedy doesn’t come from poverty, but from loss of faith, when man no longer finds truth in what he believes, when the hiatus between truth and preaching becomes too great. Examples abound.

(a classroom)

On the threshold of life, our innocent children are taught the following. “Dear children, how lucky you are to be the descendents of the Dragon and the Mountain Fairy. Your country is as beautiful as silk. Nature has been kind, filling it with gold, from the mountains to the sea.

(some Japanese children)

In a similar class in Japan, the children are taught the following: Dear little friends, you are unlucky children. Unlucky because you were born in a country without any resources. Nature didn’t give us anything. Ours is a country that has been defeated in war. The face of this country, your future, is now in your hands.

(some Vietnamese children)

If only our children had been taught this: “Dear children, the shame of poverty is no less than the shame of losing your country. Don’t listen to vain and flattering speeches, because comedy and tragedy are easily confused when the hiatus between preaching and reality becomes too great.

(a group of students pasting together a banner with the slogan “vĩ đại”—sublime)

“Hi, little friends. What do you think is ‘sublime’ in life?”

“I give up.”

“And you?”

“Frankly, I’ve heard about “vĩ đại” (the sublime), but I haven’t seen it.”

“What do you think is ‘sublime,’ sir?”

(an intellectual)

“For me, the most sublime thing ever created on earth is the human being.”

(an old schoolmistress)

“But no other living creature suffers more than man and craves decency more than man.”

Reel 4:

(the streets)

That’s true! A writer once said, “Man is a creature who refuses to live with his arms crossed. He always strains toward the superlative, the infinite, the eternal—goals that can never be achieved.” Meanwhile, life keeps moving on and never waits for… man.

Once, while looking for a location at a suburban market, our cameraman by chance spotted a man he’d respected a lot as a schoolboy.

(a vegetable vender)

That is head teacher Lê Văn Chiêu. We must admit right away that he didn’t want to be filmed while selling vegetables, for in his innocence he thought this would tarnish the image of the regime.

(a passing motorcycle)

That’s why these shots weren’t filmed by his student, but by somebody else with a hidden camera.

(a grove of trees next to an empty school)

Mr. Chiêu had for years been attached to Tô Hiệu High School in Thuờng Tín district. He was a distinguished mathematics teacher in charge of coaching final year students for the graduation exams.

(a school transcript)

Here are his comments in the transcript of one of his students, now our cameraman.

(a man with a motorcycle)

The student who in former days was a lousy duckherd has become a cameraman,

(the vegetable vender)

…while the head teacher who was so good at teaching mathematics has long since become an anonymous vegetable vender. Now, he’s an expert in fruit and vegetable seasons, as he once was in mathematics, his beloved subject. Now, he knows which vegetables to sell in which season, from water bindweed to tomatoes, to spinach…

(a man)

It’s only by chance that this cyclo driver appears in our film. He and his wife were in the 5th Zone at the same time as this film’s director and scriptwriter, during the most violent years of the war in the South. She was a doctor and he was a security man at the Party Headquarters of the 5th Zone. In 1973 he was a member of the Four Party Military Commission and finally was sent to the Southwestern Front.

(loading luggage on a cyclo)

His name is Trần Thanh Hoài. Yes, after completing his patriotic duty, a man needs to earn a living, feeling neither arrogant nor inferior about this. What could be more honest, more clean, than earning one’s living by the sweat of one’s brow? Hoài is open-hearted and confident about his current occupation.

(Hoai peddling his cyclo)

Unlike Mr. Chiêu the former teacher, he once asked us, innocently: “Why don’t you filmmakers and writers choose us cyclo drivers to be the main characters in your stories?”

“Well, we’re filming you now, don’t you see?” we replied. Having said that to put the topic aside, we also felt a bit strange…

(some poor people)

Strange since, before our Party came to power, poor people were the main characters in our stories. An old rickshaw driver, a newspaper seller, a little servant, a miserable mother, a night vender’s call…

(again, Hoài peddling his cyclo)

But now that our Party is in power, the poor have suddenly vanished from our artistic creations.

(poor people)

It is as if our compatriots are no longer acquainted with poverty and misery, or as if the poor had disappeared into the other world. To behave with each other in this fashion is not merely indecent, but quite… terrifying.

(a young man)

“For me, ignorance is even more terrifying. Mankind has no law to punish ignorance. There are no statistical systems to measure the damage caused by ignorance. Yet, in the final analysis, all painful social problems, big and small, are born of ignorance. I think no one can define it better than the founder of communism: “Ignorance is the power of the Devil.”

(an elderly man)

“If we enter into a discussion about ignorance and wisdom, I fear it will go on and on forever. There’s a saying, “Wealth breeds good manners; poverty breeds theft.” This is probably closer to life: When material life gets bad and unjust, good and evil become confused, and human dignity is diminished. The struggle for a sustainable life is also a struggle to preserve human dignity.

(people selling lottery tickets)

We must acknowledge that when human dignity is degraded, it is difficult to behave decently or to sustain higher values in all circumstances.

What do you think about this word “happiness” that appears all along Hàng Mã (“Hemp Goods”) Street? Men have written countless books defining happiness and finding ways to achieve it.

(a collection of books)

Marx wrote, “The happiness of man lies in making other men happy.” Along the street where we live, there used to be plenty of people who shared this conception, like this bicycle repairman, for example.

(a person walking)

Let’s follow Mr. Trần Xuân Tiến home to see the most cherished souvenirs from his youth.

(a row of medals)

He fought in the historic battle of Diện Biên Phủ… and in the liberation of Hanoi in 1954.

He was in the attack company of the 308th Division, which was the first to assault Khe Sanh.

He was awarded the Medal of Excellence for being the best destroyer of mechanized vehicles, and was wounded eight times.

Trần Xuân Tiến, a warrior in the battles of Điện Biên Phủ and Khe Sanh (an image from the film that was used on French posters advertising the film.

(behind Mr. Trần Xuân Tiến)

Trần Xuân Tiến retired a hero, and became a grandfather. He remained a very honest and decent person.

A man who suffered eight wounds is certainly familiar with physical pain. But physical pain, and the daily pain involved in obtaining food and clothing, are nothing compared to the spiritual pain as he contemplates his family, his people, and his country.

(an area to the rear with a woman nodding off to sleep)

Since ancient times, philosophers have expounded on the subject of happiness. The Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who lived five hundred years before Christ, wrote “If happiness means fulfilling material needs, than one may say that a cow is happy.”

Reel 5:

(an elderly woman speaking)

“For an animal such as a chameleon, happiness means to turn brown when on a dead leaf, and turn green when on a fresh one. And for a salamander, happiness means walking through fire without getting burned. Certain people are similar to chameleons: They are cunning, twisted, and adept in the use of camouflage, so as to keep out of danger. We will always suffer misery as long as people are dishonest and things are false; and as long as things are not called by their true names.”

(an elderly man)

“No, we can’t suffer forever. There are many of us who firmly believe that everywhere from West to East, morality and decency are lasting and unchanged. They’re part of our life. Without these qualities, we can no longer be human. Even in a nation or a society where people are suffering and enslaved, the inspiration for decency and perfection still exists. It is like a focal point attracting human minds, or like a beacon guiding human hearts.”

(a very elderly man)

“That’s my opinion too, but I fear that by the time society achieves such ideals, old folks like us will have already gone to the other world.”

(a funeral procession)

In the final count, be it a short or long life, decent or indecent, everyone will enjoy an equal right granted by the Creator: returning to the earth.

It has been conjectured that death is the end of things. But much can happen after death or on the path to eternal peace. Sometimes at funerals we hear solemn voices expressing regret. “What a pity! He was a decent man!” But sometimes we hear something different: “Humph! It serves that old opportunist right!”

(gravediggers doing their work)

It is indisputable that gravediggers know most about death. This may be an opportunity for us to get to know them. It’s a hard job, whether in the sun or in the rain. They’re often seen as belonging to the bottom of the social scale, but no one can avoid needing them, neither you, nor I or anyone else. But for some unknown reason, we treat them with little consideration.

(a group carrying a coffin)

Gravediggers entrust to the earth both high officials and ordinary folk, both scholars and scoundrels. However, everyone returns to the earth under different circumstances, in his own way, following his own path, and carrying his own bag of good and bad deeds.

(a grave being constructed)

And let us add that decent people always hope to see their fellow creatures enjoy a decent and quiet burial on leaving the world, a consolation of those who remain behind.

(some sad faces)

But a more important consolation for all human beings is the decency, the love, and the good deeds bequeathed by the dead to the living. Let us live in such a manner that when we die we won’t have to carry with us a sadness bigger than our own grave.

(the gaze of a gravedigger)

With the gravediggers, let us share a silent thought:

(a view of the sky)

In saying farewell to the world, how can I make sure that I am lying down not only as a decent person, but also, more importantly, as a person who has left behind a kinder world in which people feel concerned for one another?

(view of a tape recorder)

At the end of ends, none of life’s activities can be done well, and no person can be truly decent, if he or she is not guided by a deep love and respect for others and compassion for human suffering.

While we were shooting the last scenes of this film, the Director of Cemetaries in Hanoi, who is the nephew of the writer Ngô Tất Tố, said deprecatingly,

(view of a man speaking)

“It’s boring. Your topic is as old as the earth. Having worked with the dead for a long time, I find it interesting that the dead never care to argue with anybody. Of course, if they could argue, they’d reject many things, including who I am in charge of them, and even the film that you’re making.”

(packing up gear and loading it into a vehicle)

Yes, of course we’ve said nothing new, and we’d never dare to argue with anyone here, because in this ordinary cemetery, there are many literary celebrities.

The writer Nguyễn Huy Tường.

The critic Vũ Ngọc Phan.

The poet Xuân Diệu.

The writer Nguyễnn Tuân.

And many other famous personages.

(sitting in an automobile)

We’d never dare to argue with anybody, and in fact we’ve said nothing new. It’s just that we feel sorry for our unfortunate friend, who generously allowed us to film moments of his life and death and whose family had to suffer a great tragedy which we can’t relate now, but who still managed to keep his sense of humor till the end. He said,

“I’d very much like to live so that I can see how you film my death.”

(a tape recorder)

“But it has taken us a long time, a very long time, to learn that to understand the suffering of others is not an easy thing.”

No, it’s not easy. Especially if you can’t live another man’s life.

(in the car and on the road)

It’s only through living other people’s lives, sharing their joys and pains, that we’re able to discover, understand, meditate, and do a few things correctly.

(a man wearing glasses)

But like us, very few if any would be so crazy as to reject a more comfortable and powerful life in order to live the life of common people. Herein lies the paradox. Despite all our efforts and pains, what we the filmmakers have finally learnt is but a drop of water and what we still don’t know is an ocean.

(a public statue)

Having gotten to this stage, we notice that in this film, we’ve probably overused quotations from famous authors. Our filmscript written by filmmakers is possibly nonsensical and insignificant, and it will probably test the patience of certain fastidious censors.

(a burning candle)

However, quotations by famous authors should reassure everyone. They are the truth and golden words. That’s why we decided, humbly, to replace the words “The End” in this little film with a final clarification that the heated and bold statement, which said,

(written words)

“Of course, only animals turn away from human suffering and busy themselves looking after their own skins,”

How fortunately, came from the respected Karl Marx, not from my friend.

(Karl Marx’s signature)

The End

The voiceover in The Story of Kindness as well as in Hanoi in Whose Eyes was done by Mr Trần Đức in the Vietnam Television Station. At that time, he was robust, with a voice quality that was well-adapted for delivering emotional and inspirational effects.

Order In Whose Eyes from the University of Massachusetts Press, or from Amazon.

All text and images are © 2023, Trần Văn Thủy, all rights reserved. Written permission is required for any use.