Chapter Fifteen

The international delegations all hoped very much that The Story of Kindness could be shown in their film festivals, but the film continued to be hidden away. The authorities concerned did their utmost to keep everything in the dark, so that the concealment could be accomplished with a minimum of effort.

I had no rights whatsoever in this matter, even though the government had made several dozen copies of the film and had sent them around to all the cities and provinces in the country to be shown publically. At the same time, however, they also issued a very bizarre order stipulating that the film was not to leave the country. They also didn’t allow me to meet or communicate with any delegations. I was continuously trailed by the police. Conditions then were unimaginably strict. Government decisions didn’t have to be carefully thought through; it wasn’t necessary to convene meetings, or reach conclusions through discussion. Orders from above could consist merely of a phone call made by some powerful official.

The international delegations were very upset. The East German delegation angrily demanded that some way be found to send the film to Leipzig. Why were they so eager? At first I thought it was because they felt that there was something distinctive about it, or that it had something they would be able to recognize or empathize with. Only two years later did I come to understand the true reason.

At that time, representatives of the Leipzig film festival asked the organizing committee to let me go out to a site on the bank of the Hàn river1. and meet an East German female delegate for a photo session. The committee didn’t want me to have contact with any foreign representatives, but on discussing the matter among themselves, they reasoned that I was familiar only with Russian, because I had studied in Russia, and that I knew a bit of French as well, while the German delegates only spoke German. With this language limitation, I wouldn’t be able to make any plans or conspiracies with them, so they allowed me to go to the riverbank for photographs with the German woman.

But now I must tell the truth: The police trailing me and the organizing committee had no idea that this woman was a Russian and, not only that, had been a classmate of mine in Russia. She had been a student in the Pan-National Film Academy’s Production Economics Department—and after graduation she married an East German who had also been a classmate of mine.

After marriage, she had followed her husband to Germany. She and her husband were working in the Cinema Department of the Organizing Committee of the Leipzig film festival, and she had gone from there to Vietnam as a representative of that festival. Everyone thought she was German.

When we met on the riverbank, she told me everything she needed to:

“Good heavens! I could never have imagined that after the passage of so many years since we parted at the International Film Academy, we would meet again, and I would find that you had made such a film, not to speak of all the films you made before this one. I’m truly moved. Who knows what Mr. Roman Karmen would think if he were still alive and could see this film! I will only say briefly that we have little time, and that we haven’t been allowed to meet and have a free discussion, so—the long and short of it is that all of us in the delegation have agreed that this film must by all means come to Leipzig.”

“That’s wonderful, I’m very grateful to you,” I answered

But it wouldn’t be easy to ship five reels of 35 mm film, each reel 300 meters long and weighing 2.3 kilograms, together with their steel canisters. After placing those five canisters in an additional steel box, the whole would weigh about 20 kilograms.

The first problem we faced was finding a way to get hold of a copy of the film!

In principle, a film sent to an international festival should be a virgin copy that hasn’t yet been shown in a film projector and is hence free of blemishes. Secondly, what could be done to solve the problem of customs procedures? Where could we get permission? This was unthinkable and impossible.

“I’m grateful to you for your generous intentions,” I said. “I’ve been to Leipzig many times, and my first film won a prize there. It’s a place with many memories for me. In 1980 my film Betrayal was shown there as well, and I wish very much that this film could be shown there too, but the people here won’t let it leave the country. You know well how difficult it was just to get it shown to you privately.

She said, “No, I’m just telling you briefly that you must seek every means in your power to get a copy of this film into your hands. As for the means of doing this, I know nothing, so I can’t tell you what to do or discusss methods with you. As for a means of shipping the film, you must communicate with Rugerd, the cultural attaché of the East German Embassy in Hanoi. He’ll take care of shipping the film.”

I said, “Thanks very much, my friend. Please send my warm regards to your husband, and tell him that Thủy is still working hard. If I get a chance to go to Germany, I’ll talk with both of you there, but having a long conversation with you here would be… “inconvenient.” Secondly, I can’t promise you anything. Naturally, I’ll seek every possible means to do as you say, though I know this will be extremely difficult”

I had a million questions in my head. Where could I get a copy of the film? How was I going to communicate with Rugerd, so as to get the film shipped? Sooner or later people would find out that I was the chief culprit in this operation; and on top of that, it was by no means certain that the film would win a prize—a news report about the festival said that “256 films from 40 different countries would be shown. 256 films, one Golden Award, and two Silver Awards. What was the probability of getting an award?

Winning or not winning an award had nothing to do with any desire for fame on my part—the problem was far more serious: if the film didn’t win a prize, then I would go to prison! That was almost an absolute certainty. Behind my feet yawned an abyss. It was the riskiest adventure in the country!

In March 1988, upon the conclusion of the Đà Nẵng Film Festival, I joined some friends in a long tour through Vietnam in which we passed through the Central region into the South, and then back into Saigon. We went to all the places that had famous sites, friends, and lovers of cinema, so that we could show films to people, share experiences with them, and seek to know more about the lives of our countrymen. During that trip, I was constantly preoccupied with the problem of seeking a way to obtain a copy of the film. At last, I could do nothing except return to Hanoi.

Around the middle of 1988, I felt that I had to return to Saigon and the Mekong Delta to visit friends and associates. Whatever you may say about them, the people of the South are risk takers—they’re not timid, and they don’t worry about small stuff. I remember that on one occasion, while doing some shooting with Lưu Hà in Mỏ Cày District (in the Mekong delta), we were going along a river in a boat when a group of local militiamen with rifles on their shoulders ran along the shore after us and fired some shots into the air, signaling that we had to turn around and go ashore. We had to follow their orders. They said “Come here,” and “escorted” us into a hut. It turned out that they were all drinking there, and we had to follow their commands; “Drink up! Eat this!”

In accordance with the orders of the Party General Secretary, The Story of Kindness and Hanoi in Whose Eyes had been shown throughout the country, so copies of these films lay in the film repositories of all the provinces.

In the middle of 1988, I went into the South by train. Unable to buy a ticket at the station, I boarded the train and asked the conductor to sell me one. But then, having bought the ticket, there was no place either to sit or to lie down. So some people cleaned out a toilet compartment and placed a plank there for me to pass the night. The compartment was so cramped that when I rested my legs on the open window, my feet got smashed by small branches of trees growing along the railway; and if I retracted my feet, I would soon get tired and stiff. The sour smell of the dining car pervaded the whole place, and the door could neither be securely shut nor entirely opened, so it swung back and forth, making the light from outside shine on and off in my eyes. Around two o’clock in the morning, a stranger stopped outside and, fixing his gaze on me curled-up in the cramped apartment.

- “Are you anh Thủy?” he asked.

I was startled. People who have been trailed by the police are hypersensitive. “How can he know who I am?” I thought to myself.

- “Umnn, why are you asking?” I asked.

I dared neither to confirm nor to deny it, because I didn’t know who this man really was. Then he continued,

- “So, it’s you, right? Last week you came and talked at the Railway Club, showed films and chatted with the audience. I was also there that day. The Railway Department chiefs are on this train for an inspection. But why are you lying so badly in such an uncomfortable spot? Let me go and report to them.”

Some of them came rushing to see me… After that I was taken to an upper compartment, where I was provided with amenities and meals with special care…

When the train arrived in Saigon, these gentlemen introduced me to the local railway authorities, saying, “Take anh Thủy to the guesthouse of the Department, and see that he gets to eat and rest properly while he’s here, and then give him a ride back—he’s an honored guest of the Department.”

During my days in the South, I was able to get a clean copy of the film, thanks to the help of a friend willing to take risks to help me. It was a copy of the finest quality that had not been shown even once. Even now, I cannot reveal the identity of that person. I shall take this occasion to send an open letter to this close friend of former days:

To my good friend T.

So a whole quarter of a century has passed since 1988—in that year, because you liked and innocently trusted me, you found a copy of The Story of Kindness of the highest quality, and discretely put it into my hands, so that it could be shipped to Leipzig at the end of the year. I want to thank you a thousand times and I do so also on behalf of millions of TV viewers, film festivals, conferences and universities all over the world. I cannot (or cannot as yet) address you by name in this open letter, for fear that this might involve you in trouble. Your life has already been troubled enough, for you are sincere and honest; you’re a person who loves his profession and loves other people. You took a risk when you helped me in a dangerous but immensely important matter that was of benefit to our society and our country, without any expectation of personal gain. Allow me to share some thoughts with you, because, due to our friendship, you have forgiven me many things. You were aware, as I was, that if The Story of Kindness didn’t win a prize, it would be difficult for me to return to Vietnam—if I returned, I would be put in prison. And if the film won a prize, I wouldn’t gain anything from it. I would have to keep running and hiding. And if the rights to the movie were sold elsewhere in the world, I would still not get a penny for it. Thinking the matter over, I see that this was a gamble, a quasi-supernatural gamble, in which we seemed to be guided and protected by spirits, don’t you think? It might even be said that it was a gamble made by martyrs who believed in their profession.

My dear friend, time flows on inexorably, and we’ve grown old, haven’t we—but I still remember you and your family with all my heart, and pray with all my soul that you enjoy peace. And so, if you read the portion of this book about the flight of The Story of Kindness to Leipzig, you will see that those who owe thanks to you for your role in this are not limited to Trần Văn Thủy.

Filmmakers always have a steel box to carry their reels of film, their equipment, and their money. I put the film into this box and boarded a train going back to the North.

Only when the film was in my hands did I start to think about how to get it to Leipzig. To tell the truth, none of the colleagues who worked on the film with me know to this day how the film “escaped across the border,” and Lê Văn Long the cameraman even guessed that I borrowed the film from some Vietnamese living overseas.

The police followed my every step and monitored all my relations with others. No one dared do anything as risky as what I planned. Back then, you had to have clearance documents even to carry a cassette across the border.

I wasn’t seeking anything for myself. I wasn’t seeking profit, fame or money. The key thing was that I felt that this was necessary and would benefit my country. When I make a film, I never think about getting a prize, getting a raise in salary, or gaining prominence; I do it purely to satisfy myself. But when I speak this way, many people put it down to hypocrisy.

Recently, a young American film director came to our studio and had a conversation with our director, who asked, “When you start making a film, what’s most important to you—the audience, the publicity, the money, or your reputation?” The young director said, “All these factors are essential.”

But when I start making a film, there is only one thing I wish to know: Will the film make the viewers happy? I have never made a film to please my superiors, or to show that my political thinking is in line with official policy, or to win a prize, or to make a name for myself. I absolutely do not think of these things—and I say this before the altar to my ancestors. However I act, I act as Heaven directs me to act.

Back then I lived at 52 Hàng Bún Street. My house was always under surveillance by the police, who did their watching in two groups, one on Hàng Bún Street, and the other on Yên Ninh Lane. I went to a telephone I didn’t ordinarily use, and dialed Rugerd’s number. I didn’t know German, but Rugerd was fortunately fluent in Vietnamese.

- “Is it Rugerd? How are you doing?”

- “Anh Thủy! I’m doing fine!”

- It’s so depressing! We haven’t met for a long time—I want to go out to alleviate my stress, or sit somewhere to relax a bit—let’s go out for a coffee.

- Yeah, let’s go for a coffee.

Back in that period, merely going somewhere with a foreigner was in itself was taking a risk. We sat in an empty place on Bà Triệu Street and drank coffee. It was a café run by the artist Ngọc Linh, who also worked in the cinema industry. As we sat and chatted I examined the surroundings. Seeing nothing unusual, I said,

- “I have a copy of the film.”

- “Oh, marvelous!”

- “I’m just saying this so that you’ll know—as to what’s to be done next, the Leipzig Festival people told me that this will be decided by you.”

- “Take it easy. We Germans aren’t necessarily very talented, but we work in an extremely precise manner. Next time when we go out for coffee, I’ll tell you exactly what must be done.”

On the next occasion, we sat, drank coffee, and talked about everything under the sun while looking up and down to see if anyone was tailing us. Then Rugerd said:

- “You listen carefully! At 3:00 pm this Sunday on Bạch Thảo Street, a white car with a diplomatic number plate will be parked along the right side of the road. The trunk will be open. I’ll be standing on the sidewalk smoking, with my back to the car. Do whatever is necessary to throw the film into the trunk without anyone seeing you. Then disappear—leave the rest to me”

It was like a detective story. I drove my Honda 82 motorbike and set out from Hàng Bún Street. The film casket was behind me, unsecured. I went past the red gate of the Presidential Palace. Bách Thảo Street was very empty on Sunday at 3:00 pm. In the distance was a white car with an open trunk parked by the side of the road, and a man standing on the sidewalk with his back to the car, who looked as if he were smoking.

When I was still fifteen to twenty meters away, I saw a few people coming in the opposite direction from Ngọc Hà Street, and immediately revved my motor and sped past the white car. When reaching the Ngọc Hà intersection, I turned around, drove back, surveyed the scene again, and saw that it was empty. I drove at an even speed, my right hand on the gas control, and with my left hand—I’m left-handed—threw the heavy metal casket into the trunk.

I make documentary films only, but the dramatic situations that arose when I made the films, and the ups and downs that the films passed through after their production could become the subject matter for a long feature film.

If such “feature films” are produced, they will have the opening and suspense, the climax and explosion, and the thrill just like real “cinemas”. Moreover, they are special in the sense that nothing in them will have to be made up, because all of the stories, personages, and events in the films, though real, will unfold in a way that could occur only to the most imaginative minds that this episode is but one example.

…From that time until this moment, I have never had any idea how the film copy was shipped, through some kind of diplomatic channel or what.

In the meantime, our officials in charge of cultural and artistic affairs were still engaged in ceaseless discussion concerning the issue of delivering or not delivering the film to the festival. Many supported the idea of delivering the film.

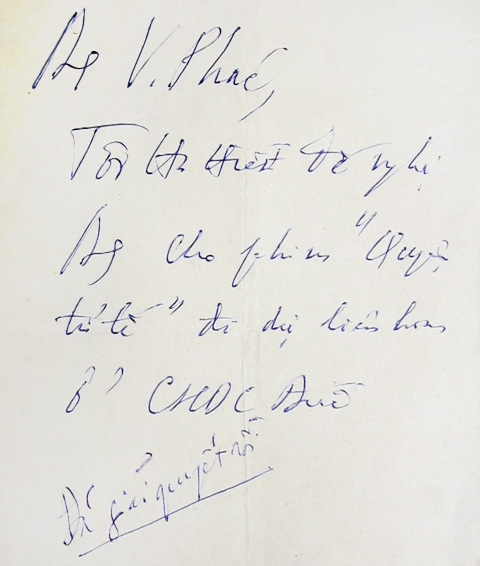

On August 24th 1988, a meeting took place at 49 Phan Đình Phùng Street in which Mr. Nguyễn Văn Hạnh—the Deputy Director of Culture and Art Department (Mr Trần Độ was Director)—and Mr. Văn Phác—Minister of Culture—took part. For some reason, I also was present at the meeting. Mr. Nguyễn Văn Hạnh wrote something on a scrap of paper, then pushed it over to Mr. Văn Phác. Mr. Văn Phác wrote a few words on it, then pushed it back to Mr. Hạnh. Mr. Hạnh read it, then pushed it over to me, saying, “That’s it, now it’s ok for you to go; you can put your mind at rest.”

The note written by Nguy Văn Hạnh to Mr. Văn Phác.

I quickly read the scrap of paper:

- “Anh Văn Phác, I earnestly suggest that you allow the film “The Story of Kindness” to be sent to the Film Festival in the Democratic Republic of Germany”.

- “This has been approved.”

According to the rules of etiquette, I should have thanked him and returned the scrap of paper to him after reading it; but instead I folded it and put it in my pocket, for protection later.

Later on, during the many occasions when I was detained and interrogated concerning this matter, I had to produce this scrap of paper. It had on it their handwritten evidence, not typewritten words.

As for the film, I didn’t take a copy with me. They kept discussing whether or not they should agree to send the film, and whether or not they should “edit” the film. This went on almost until November 1988.

| 1. | The Hàn is north-flowing river leading to the Bay of Đà Nẵng, in Central Vietnam. |

Order In Whose Eyes from the University of Massachusetts Press, or from Amazon.

All text and images are © 2023, Trần Văn Thủy, all rights reserved. Written permission is required for any use.