Chapter Sixteen

In former days, going to foreign countries was extremely difficult. Even trips undertaken purely for government business or for professional reasons were not as simple as they have now become. There were many occasions when a film festival or a conference would invite somebody, and the leadership would send somebody else, who had no connection with the business at hand, in that person’s stead. It was due to this that the letter of invitation from the Leipzig festival sent to Trần Văn Thủy (Sehr geehrter Genosse Trần Văn Thủy) explicitly stated that this invitation was for the person specified only, and could not be applied to anyone else (Diese Einladung gilt nur für eine Person und ist nicht übertragbar).

The Germans were well aware of my situation. They knew that the shipment of The Story of Kindness to Leipzig was a very risky business, as two of their representatives had already witnessed the petty complications concerning the issue of whether or not to show the film at the Đà Nẵng festival in March 1988. A point worth noting is that though the Leipzig festival would not take place until the end of November 1988, the letter of invitation was dated October 6th 1988. They understood the bureaucratic decision making processes in this country pretty well.

Close to departure, I was invited to a meeting in which the leadership would present their decisions to me. The meeting included Mr Bùi Đình Hạc, a Deputy Director of the Cinema Department, which at that time was called “Liên Hiệp Điện Ảnh” (Cinema Union), and Mr. Cao Nghị, another Deputy Director in charge of finance. In addition, there were some people in charge of foreign relations, security, and some others as well. Mr. Bùi Đinh Hạc, representing the leadership, said,

“We have received the invitation from the Leipzig film festival, and the leadership has decided to allow anh Thủy to go. To ensure that the mission is done in a good and responsible manner, Mr. Cao Nghị shall act as chief of the delegation. Mr. Cao Nghị will have the responsibility to oversee and direct the mission. In other words, both of you can go; but the film absolutely cannot go there. If anything should happen, and if The Story of Kindness shows up in Leipzig and is shown at the festival, then the two of you, and especially Mr. Cao Nghị, will bear the responsibility for this.

In that era, people going abroad were often given such precise warnings. One of the people at the meeting that day was Nguyễn Văn Tình who worked for the Cinema Department’s foreign relations. Currently he is the chief of the International Cooperation Department of the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism.

When Mr. Bùi Đinh Hạc had finished speaking, I asked, “Have you finished?”

He said, “That’s all the points I need to communicate.”

I asked,“Are the things you have said simply the thoughts of friends and colleagues offered to me before I leave, or are they orders from the leadership?”

Mr. Hạc said, “These are orders from the leadership. You must not allow The Story of Kindness to be shown in Leipzig!”

I also responded in a frank manner, “Anh Hạc, if you’re worried that this may happen, then you’d better take necessary formalities to keep me here—because my nature is different from others that after I’ve crossed the border, I won’t be able to remember a thing, and anything may happen.”

Maybe they thought I was just boasting. I made an additional remark: “It is now Saturday morning (back then people worked even on Saturdays). You still have the afternoon to arrange to keep me here. If Sunday passes, and nothing happens, then on Monday morning Mr. Cao Nghị and I will go to the airport as planned, and we will then fly out of the country. After that I don’t know what will happen.”

On Monday morning, I went with Mr. Cao Nghị to the airport, and we flew to Moscow, and then to Berlin. From Berlin we went more than 300 kilometers by car to Leipzig, a city in the southeastern sector of Germany. When we got there, we were led directly to the executive committee of the festival, where we did the paperwork, received our badges, programs, money, and introduction letters to the Astoria Hotel for check-in. The Astoria was an old hotel, the finest in Leipzig at that time.

About half an hour after we moved into our room, a knock came at the door. Before I could even ask who it was, the doorknob turned, the door opened, and a person appeared, who introduced himself: “I’m a security man from the Vietnamese embassy in Berlin, and I’ve been sent here on special assignment by the ambassador to meet the two of you to find out and confirm whether the film The Story of Kindness is available here or not, because we’ve got an order from home that this film must not appear in the festival.

I told him that I was just a delegation member, and that the person in charge was Mr. Cao Nghị. But he continued to wrangle about the same subject: “Did you people bring anything with you? The ambassador is waiting on the other end of the line in Berlin.”

Mr. Cao Nghị was sincere and gentle by nature, and he moreover suffered from a heart condition. I had to think about protecting him, and feared that some mishap might befall him. I felt sorry for Mr. Nghị—I felt that I was in some way being unkind to him because he was a decent man who had been forced into this awkward situation. He knew nothing about the real situation, and kept trying to explain:

- “What a pain! The film canister is so big; it’s not something so small like a matchbox that could easily be hidden. We went through the customs with all the proper paperwork. As for the film, only the government has it; how could any individual have it that you should ask such a question!”

The security man said, “The program has the film listed for showing on the 27th of November at 8:30 pm at the Capital Theater.”

Mr. Cao Nghị said, “Then go to the executive committee of the festival and ask them about it. We just got here, and have only just now moved into this room. We were told to stay here, so this is where we’ll stay! We haven’t even had time even to wash or eat anything!”

My wife’s younger brother was just then sitting in the inner room. His name was Dũng (Nguyễn Tiến Dũng). When he saw how tense the situation was, his face turned pale with alarm. When I entered the inner room to get some papers, Dũng said to me in a low voice, “Anh Thủy, you’ve got to step back —you have to think of your wife and your children! If you take one more step forward, there will be no way to go back home!”

I drew close to his ear: “There’s an abyss behind me—Now I can’t step back even one millimeter!”

I had to act in this manner because I didn’t want to be isolated and beaten up. If I had been cowardly and allowed myself to be bullied, so that no one in other countries could see the film, I would have been buried alive.

Among the 256 films to be shown (as announced in the newspapers), what were the chances that my film would win a prize? If it didn’t win a prize, I would have to live in exile, and find some restaurant, where I might have washed dishes until today.

That was what I most feared—having to live abroad, to live far from my homeland, far from the graves of my ancestors. I was accustomed to the smell of incense and smoke, the smell of straw and rice stubble. It’s been almost thirty years since that time—I have reflected many times that if I had lived in exile all that time, then today there would be no Sound of the Violin at Mỹ Lai, If I Go the End of All the Seas, A Barbarian of Modern Times, and no Melodies Echoing Through the Ages. And there would also be no fine bridges, roads, and schools rebuilt in my home village.

The security man kept going over the same points with Mr. Cao Nghị at length until he went to speak with the festival executive committee. I don’t know how he spoke with them; perhaps he tried to make himself sound authoritative—in any case, the executive committee’s reply was “We can speak only with the Vietnamese Ministry of Culture.”

Throughout our days in Leipzig, from the Nov. 20th to the 27th, I couldn’t eat or sleep, and grew thinner and thinner as I waited for The Story of Kindness to be shown.

And all this was to gain what? If the film didn’t win a prize, then if I returned to Vietnam I would be a criminal, and if I didn’t return, I would have to live in exile, abandoning my obligations to the graves of my forebears, abandoning my wife, children, and friends.

I never sought fame or honor; I longed only to do something useful. I imagined that when foreigners saw that film, they would be moved, and feel affection for Vietnam. They wouldn’t think that it was a film by Trần Văn Thủy, but rather that it was a Vietnamese film.

The people in charge of cinema in Vietnam had at their disposal a way of raising Vietnam’s staus in the world, but they didn’t know how to do it; instead they regarded me as a criminal. As for my mother, she kept weeping as I got involved in one problem after another: “My son! Why do you make yourself so miserable! Phúc isn’t like that at all!”

Phúc was her son-in-law, the husband of my younger sister. He made films that were cheerful and positive, so that he could bring home chicken and duck eggs as by-products. He made films about science, so everywhere he went, people would bestow gifts on him. This delighted my mother, who would say, “See—if you make films, you have to make them the way Phúc does. When I see you making gloomy films, as if you were dealing in counterfeit money, I get so worried that I can’t sleep, son.”

Such were my circumstances. Before going to Germany, I had received an invitation from the Vietnamese Association in France, and had received a signed decision from Mr. Trần Độ allowing me to go there. I had gone to the French embassy and obtained a visa. Actually, going to France in response to the invitation of friends was a very lucky thing for me, and I was also eager about it, because I had never previously set foot in France. But the most important point of all in the situation that now faced me was that I had a path of retreat in case I should meet with an ugly situation. That path of retreat was France. I could remain there.

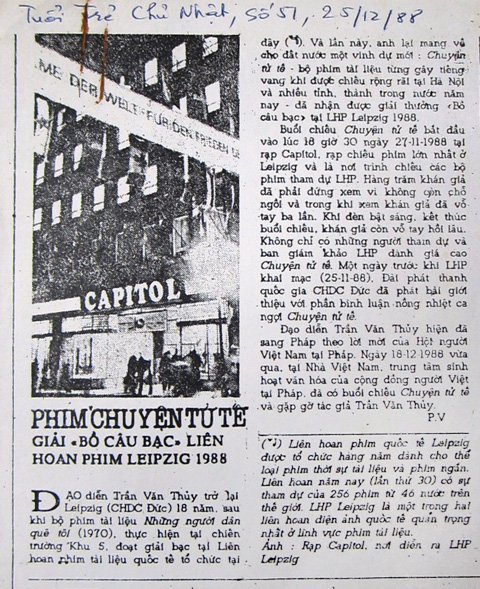

Issue #51 of the Tuổi Trẻ (Youth) Sunday newspaper on December 25th 1988.

On the afternoon of the 27th, I asked my younger brother-in-law Dũng to take care of Mr. Cao Nghị. I instructed him as follows: “Take anh Cao Nghị to your dormitory. See that he gets a good meal and is able to rest. He should drink wine only. After that, find some pretext to have him pass the night there; don’t let him go back to the hotel or to the movie theater.

Dũng did just as I instructed him. He invited Mr. Nghị to drink some light wine, then spoke to him in a very friendly manner: “So, my brother, it’s late already, and it’s started snowing. Stay with me tonight, then tomorrow when I go to work I’ll take you back to the hotel.”

While Dũng was doing this, I went out to the Capital Theater. The scene there was just as it was later described in the Dec. 25 1988 issue of Youth Sunday newspaper: there were no places to sit anymore, and people stood in closely packed crowds; more closely packed than can be imagined, and while watching the film, the spectators applauded three times.

When the film was over, all the members of the audience rose to their feet and clapped. My friends were there in great numbers; these included classmates of mine from Russia, and friends I had made at various festivals, and international conferences…

“This is great fun,” I said. “I’m very grateful; but please excuse me, I’ve got to attend to a little task.”

I went upstairs to get may stuff, which has been packed up in readiness, and left a slip of paper with a message on it that I had written in advance: “Dear anh Cao Nghị, I have to go to Berlin for a few days to buy a ticket for the trip to Paris. Please remain where you are and eat carefully to safeguard your health. Dũng will take care of everything for you. As for all that concerns the film and the prize, with or without it, please let me decide.”

I had to write these things because I was afraid that Mr. Nghị might intervene with the executive committee about this and that. I placed the slip of paper at the head of his bed, then took all my stuff and disappeared at once from Leipzig.

Order In Whose Eyes from the University of Massachusetts Press, or from Amazon.

All text and images are © 2023, Trần Văn Thủy, all rights reserved. Written permission is required for any use.