Chapter Seventeen

(In the English book this chapter is combined with the previous one)

Many people believe that you have to go to Berlin to find a train that goes to Paris, but that’s not the case; a major train hub lay right next to the Astoria Hotel. The Leipzig train station is regarded as one of the major train stations in Europe, but at that time, it was as dark and cold as a grave. I took a train to West Germany. If I had remained in Leipzig that night, I would surely have been seized.

During this Leipzig to Paris journey, West German customs officials boarded the train to check the passengers’ papers as soon as the train reached the West German border. I didn’t have a West German visa! Only then did I learn of a detail about the journey: on reaching the Frankfurt on Mainz station, it was necessary to get out and change to a different train. But to step down to the train station floor was to set foot in West Germany—you must have a visa! “Oh no! If they make me get out at this station and take me into custody, the game is over!”

They questioned me again and again in German, French, and even Russian, but from the beginning to the end, I said only the following brief phrases in English: “I am a film director–Hanoi–International Film Festival Leipzig–Paris.” Pretending that I didn’t know Russian, I just repeated these phrases over and over. The train had to remain stationary for half an hour due to my situation.

Several West German frontier soldiers kept questioning me, but when they saw that I just kept repeating myself, they grew disgusted—how could they converse with a fellow who just said the same thing ten times over?! They finally threw my passport into the corner where I was sitting, waved their hands, and went away.

I was totally worn out. In my hands was a cloth sack with few changes of clothing and a cake of steamed rice that my brother-in-law had wrapped for me the other night. There were also a few pieces of stewed pork and some pickled cucumbers, not separately packed. The sour juice of the cucumbers had seeped into the rice, so it was hard to swallow.

When the train reached Frankfurt on Mainz, the shops were dazzlingly illuminated. As part of West Germany, Frankfurt on Mainz was part of a capitalist country—this was the first time I had been to one. I changed trains at that station, and after that arrived at the German-French border. By then I was exhausted. My rice tasted like rotten dregs left in a cooking pot and I couldn’t swallow it. I went into a restroom cubicle to wash my face and drink some water to ease my thirst. A French border guard thought I was some kind of stowaway and started violently kicking the door. I stepped out, my face haggard, and with ragged clothes, as if I had just crept out of a pile of garbage.

The border guard questioned me haughtily, assuming that I was a criminal trying to slip past the border.

I said, “Je suis Trần Văn Thủy réalisateur. Je suis invité ici par le responsable. Attendez-moi un peu, je viens là-bas pour prendre mon passeport.”

(I am Trần Văn Thủy, a film director. I have been invited here by those responsible. Please wait a moment while I return to my seat and get my passport.)

When he had finished examining my papers, the border guard made a classic formal gesture—he bowed nearly double at the waist and joined his arms to make a circle, and, indicating the exit, said, “S’il vous plaît, monsieur.” (“This way please, sir.”)

The name of the station at the border was very easy to remember: “La Fontaine,” the author of the lines, “The cicada sadly hums…” Then the train came to Paris. I had been invited for the 1st of December, but I had somehow made my way there by the 28th of November!

Public phones in France are more complicated and have more buttons than the ones in our country. I didn’t know which buttons to push, and I hadn’t even a penny in my pocket. I kept looking closely at other people as they used the phones, to observe what they did. On seeing a benevolent-looking old lady, I held out the phone number for her to see, so that she could help me. She gave me a few coins, but I told her I didn’t know how to make a call, so she dialed the number for me and handed me the receiver. On the other end of the line was a woman’s voice speaking Vietnamese.

- “Hello.”

- “Miss, may I ask if you are from the Vietnamese Association in France?”

- “Yes, what can I do for you, sir?”

Only then did I thank the old woman who had helped me, and only when she left did I say, “Miss, please speak with me very clearly—if you hang up, I’ll be stranded here. I’m Trần Văn Thủy. You all sent me an invitation, but it was for December 1st, and today is only the 28th of November. Can you help me make contact with anh Trần Hải Hạc, anh Nguyễn Ngọc Giao, or anh Bạch Thái Quốc, so they can come pick me up?”

- “No problem, you can rest easy. Where are you standing? What station are you at?”

- “I have no idea what station it is; I just know that it’s the station you get to when coming from West Germany.”

- “What location are you standing in?”

- “I’m standing inside the station.”

- “Look and see what the number is of the rail line that you’re next to.”

- “I’m standing by rail line no. 13.”

- “Stay right where you are, okay? Don’t go anywhere else.”

Only later on, after going to France many times, did I learn that the station is called “De l’Est” (East Station). When people call and make arrangements to meet or greet each other in Paris, it is generally necessary to do so several days ahead of time. To call in the middle of the night and tell someone that you’ve arrived is next to impossible.

But, 40 minutes later, anh Trần Hải Hạc ran straight to where I was standing at rail Line 13. He was wearing denim jacket with a white feathered garment underneath, the lower flaps of which flew along in the air as he ran! The first thing I said to him was,

- “Anh Hạc, is my early arrival causing you any trouble?”

- “No, no, no; no trouble at all. We’re very happy you’ve come; it’s no trouble at all!”

During my many trips to Paris over the years, I have usually stayed at Trần Hải Hạc’s house at place d’Italie in Arrondissement (district) 13.

Through him I have had the good fortune to make the acquaintance of many friends, and he and I have grown very close. The people in his circle are very sincere, very attached to the Vietnamese homeland, and share wholeheartedly the joys and sorrows of their compatriots at home. Nevertheless, it would not be appropriate to talk about them here, for many reasons.

…In 1946 when Hồ Chí Minh went to France for the Fontainebleau Conference, he was photographed holding in his arms a one-year-old Vietnamese child living in France. That child was Trần Hải Hạc.

After the 1989 “tâm thư” (letter from the heart) incident,1 Trần Hải Hạc’s name and those of many other people in the Vietnamese Association in France were blacklisted. When these people went back to Vietnam, they were followed by the police; and they sometimes found it hard to return to Vietnam, even if they weren’t refused entry altogether…

A few days after my arrival, the Vietnamese Association in France assigned Ms. Thanh Thiện the task of taking me out to get “outfitted.” She wrote me a check for several thousand of francs to buy me new sets of inner and outer clothing—she even asked me to take off my shoes, to see if my socks were torn.

So I became a fashion plate. And for what purpose? So that Trần Văn Thủy could go on a speaking tour and converse with audiences in many parts of France.

News of The Story of Kindness in the newspaper Libération.

But the thing that made me almost crazy with anxiety then was of course the results of the International Film Festival at Leipzig. I read newspapers all day long, and came across different publications. The longest article about me and The Story of Kindness was by Elizabeth D. in Libération. Le Monde Diplomatique ran an article by the famous journalist Jacques Decornoy, and then there were notices in Le Peuple du Monde, Le Figaro, Le Telegrama, Le Gardien, and many others. On reading Le Monde Diplomatique and then Libération, I saw that they had printed the results of the Leipzig Festival.

Oh good heavens! The Story of Kindness appeared among the titles of the prize-winning films! I was in an inner room at the time; anh Trần Hải Hạc was sitting in his study on the other side of the kitchen.

“Ha-hah!” I shouted. “I’ll be able to go back to Vietnam now!”

I was perpetually consumed by the question of my return home—how could I do it without getting into trouble?

Just recently, In December of 2012, my brother-in-law Dũng and his wife went back to Hanoi to visit the family. I asked him about what had happened in Leipzig at that time, and Dũng still kept a good memory about Mr Cao Nghị. He recounted some more details:

On the night of November 30, 1988, at the conclusion of the festival, the awards ceremony took place in the Capitol Theater. When the executive committee announced that The Story of Kindness had won the Silver Dove Award, the spectators, nearly a thousand of them, burst into applause. The Vietnamese delegation was invited to come on stage to receive the prize.

Dũng said to Mr. Cao Nghị, “Come on, you go up and receive the prize!”

Mr. Cao Nghị demurred: “The director’s disappeared. I’m not going up there for anything—If I accept the prize, it will be my death warrant when I return!”

When Dũng reached this point in his story, I suddenly felt bitter. I wonder if, in the history of world cinema, has there ever been any case where the author of a prize-winning film at an international festival has had to undergo such a bizarre and miserable experience?

At that urgent juncture, it became necessary for Dũng to accept the prize on behalf of the Vietnamese delegation. Fortunately he was a tall and good-looking young man who had lived in Germany for a long time and consequently spoke German like a native.

Even up to this very moment, nearly thirty years after the event, I still have no idea what the prize looked like, or where it now exists.

Anyway, I remained in Paris for three months, until March 31 1989. Mr. Cao Nghị returned home wretched, anticipating the worst. He submitted a detailed report and a critical review to the Ministry of Culture and the Police Department, where he was repeatedly dragged over the coals. Now, every time I think of this event, I have a feeling of guilt, a feeling that I failed to do right by him. But I have no regrets whatsoever with regard to any other aspect of the matter. The problem lay not with Mr. Cao Nghị or with me, but elsewhere. Mr. Nghị was made wretched, and I too “skinned my shins and elbows” many times, and was aware that many others were also suffering for no reason at all. Did they deserve all that? And what has this wretched country gained by acting like that again and again? Well, let everyone judge this for themselves.

…Recently I made a phone call to Mr. Cao Nghị. He lives in Saigon these days. When I touched on the former events in Leipzig, all he said was, “You were very courageous and did many useful things…” As for the severe interrogations he had had to endure afterward, he only mentioned them in passing, but everyone knows how harshly he was treated.

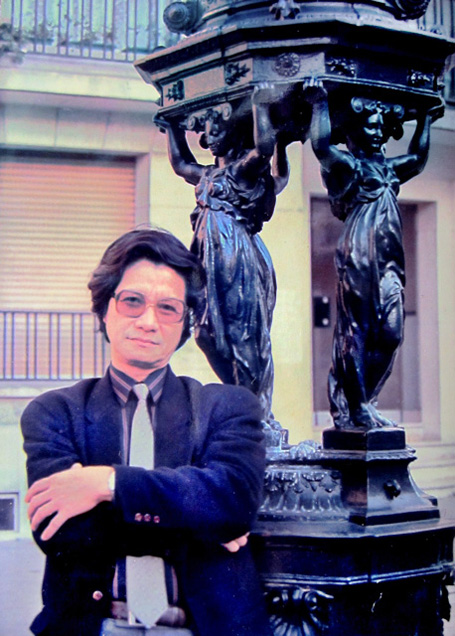

The panel of judges in the 1989 Leipzig Film Festival. Trần Văn Thủy is the third person from the right.

My German colleagues, on the other hand, were very kind to me. In the following year, 1989, they invited me to join their panel of judges in the last film festival that would be held there before the government of the Democratic Republic of Germany was overthrown.

I was in France at the time, so I didn’t have to seek anyone’s permission, or make a report to anyone. From Paris I flew directly to Berlin and then to Leipzig. The films submitted for consideration that year were very fine, especially the film Parade from Poland. I gave the film a full ten points, and later on it was in fact given the Golden Dove Award.

I returned to Paris and Western Europe, remaining there until the beginning of July 1990. That was when a series of momentous historic events occurred: the Berlin wall came down. The socialist governments of the Eastern block countries disintegrated, and the Soviet Union also fell apart… I was naturally able to obtain direct and truthful reports of all that occurred. In a number of places we were able to film events that later became part of the film The Blind Wise Men Examine the Elephant.

I returned to Paris and Western Europe, remaining there until the beginning of July 1990.

| 1. | This refers to the much-publicized case of two sisters arrested in Vietnam for drug smuggling; one was sentenced to death and the other to twenty years in prison. The “tâm thư” was written in prison by the second sister. |

Order In Whose Eyes from the University of Massachusetts Press, or from Amazon.

All text and images are © 2023, Trần Văn Thủy, all rights reserved. Written permission is required for any use.