Chapter Eighteen

It is with the greatest reluctance that I divulge my dissatisfactions concerning money matters; but I must speak out so that everything may be clear, and so that everyone may become familiar with a lesson written in blood: Don’t get involved in money matters; for if you do, you will one day be crushed dead like a swatted fly—but the crux of the matter is that, in Vietnam, the state (or more specifically the agency in charge of cinema) doesn’t work in a transparent manner with filmmakers.

In the world of (documentary) film, and more generally in the world of literature and art as a whole, it is very rare for a work to enjoy a reception as warm and enthusiastic as that which greeted Hanoi in Whose Eyes, and The Story of Kindness when these films first appeared before national and international audiences. This warm reception was due above all to the thoughts, feelings, and perceptions expressed in these films, which found a ready response in the reflections of viewers on contemporary affairs.

But this led to a second factor, which, to put it crudely, was… money!

If these two films had not been accepted and allowed to exist, I would have been implicated in crimes against the state, and so would have been subject to an endless round of punishment. That the two films were accepted meant that they earned money, all of which went into the pockets of the government. If the money had been spent for useful purposes, I would have nothing to say. The problem lies in where the money went, and what it was used for. Even now, no one knows anything about that.

After the leadership turned on the green light, Hanoi in Whose Eyes and The Story of Kindness were shown continuously for several months throughout the length of Vietnam in all the large theaters, outdoor venues, and all the government clubs and associations… Where did the money earned from movie rental fees go?

And the money earned by selling the rental rights to a dozen major foreign broadcasting networks—which amounted initially to a hundred thousand US dollars—where did that money go?

In this connection, allow me to go a bit further. It seems that there has never been an administrator or film critic who focused on such a crude matter as money. Money is obviously not the ultimate objective in filmmaking; but it is surely worth pondering that this was the first time in the history of Vietnamese cinema that two films earned such large sums of money for the government.

But before this occurred, Hanoi in Whose Eyes had been banned for five years (1982–1987) and The Story of Kindness banned from exit overseas (1988).

It is surely a joke of destiny that people should have been so indifferent with regard to a fact worthy of being entered into a Vietnamese Guinness Book of Records. From the time of the birth of cinema in Vietnam, documentary films had never earned a penny. Most had been devoted to the glorification of “the powers that be.” They required large investments, were laborious to make, and plagued by mishaps. They were censored with the utmost solemnity from beginning to end. And after all this, they were shown only a few times and in the end… thrown into “storage.” Documentary film studios in Vietnam seem to have gone on in this fashion for more than half a century and were continuing to stumble along in this sort of limbo.

Naturally, a few works of value had appeared in this long process and had won certain prizes, but there had never been any film whatsoever that had made such a lot of money for the government (in a few cases some studios might make some money through the sale of footage shot in wartime to foreign companies for their own documentary productions). Some people did feel sorry and concerned about this state of affairs, and thought hard about it; but, unwilling to deviate from policy, and hemmed in as they were by “clear directives,” they would eventually cluck their tongues and let it go. Everyone knew that in advanced countries, things were completely different.

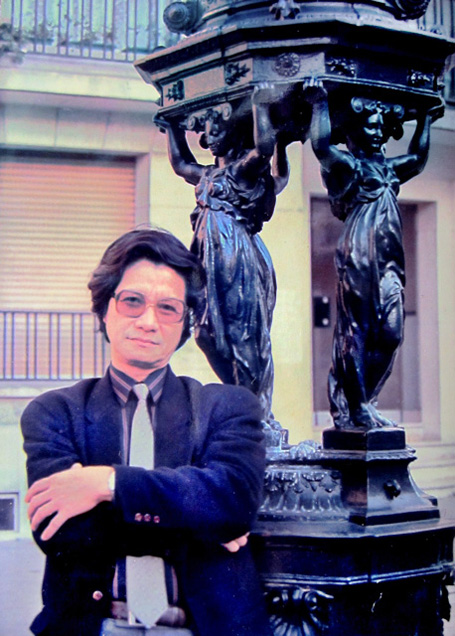

The panel of judges in the 1989 Leipzig Film Festival. Trần Văn Thủy is the third person from the right.

In these circumstances, I and a number of my colleagues were often uneasy about taxpayers’ money being spent so thoughtlessly, and this was going on and on.

When The Story of Kindness suddenly appeared at the Leipzig International Film Festival in November, 1988 after many failed attempts to ban the film and prevent its appearance elsewhere, the film administrators were flustered and confused. They couldn’t understand how the film had suddenly burst into view and won a prize after all their bans, threats, and checks. This was an “honor” very hard for them to endure.

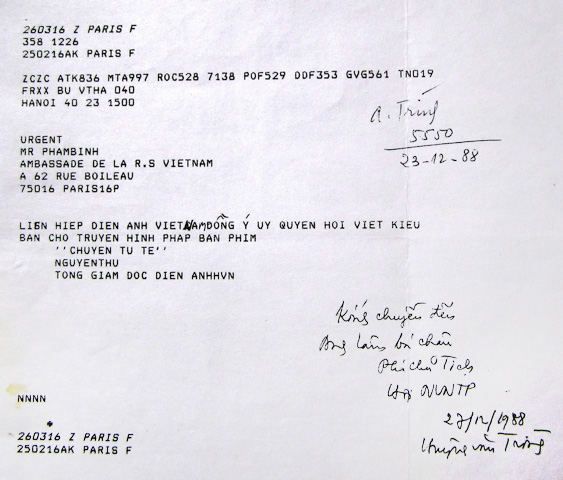

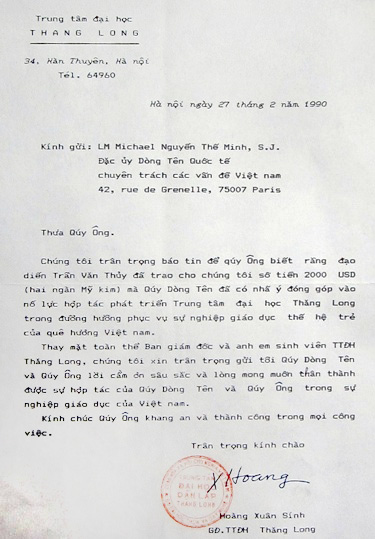

After several dozen meetings at all levels of the government to discuss how to deal with the situation, they at last had to grit their teeth and announced their decision. The Union of Cinema Associations of Vietnam sent an official telegram on behalf of the government to Ambassador Pham Binh in Paris authorizing the Vietnamese Association in France to sell the TV rental rights to all interested foreign TV stations. Mr Christopher Walker, the director of Icarus International Films, an American company, signed a contract making him the intermediary in selling the right to show The Story of Kindness to a series of broadcasting stations throughout the world. Icarus was a prestigious company, so these rights were sold at a handsome price.

The official telegram from the Union of Cinema Associations of Vietnam authorizing the Vietnamese Association in France to sell the rental rights to The Story of Kindness.

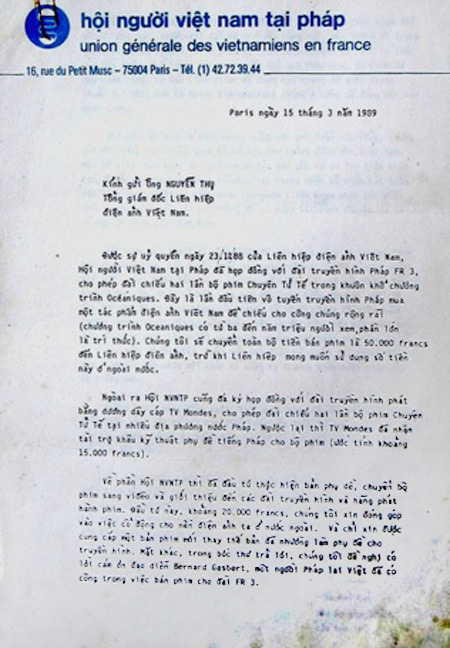

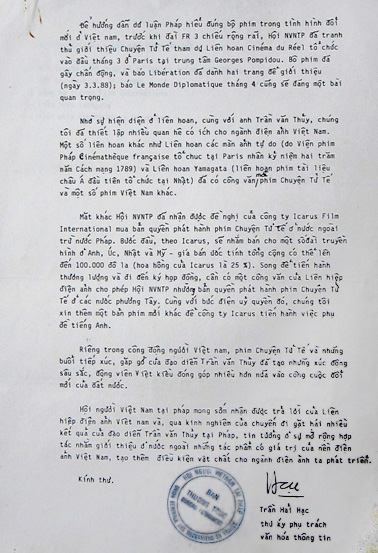

To ensure that the money from these sales would reach Vietnam intact, as specified in the contract, all the transfer and banking expenses were paid out of my own pocket and those of the people in the Vietnamese Association in France. My friends in France and people in the Association spent almost twenty thousand francs so that all the procedures could be completed and the money transferred to Vietnam intact without loss. The attached letter from the Vietnamese Association in France to the Union of Cinema Associations, which referred to the amount of money, included the following sentence: “To begin with, according to Icarus, they will aim at selling the film to a number of broadcasting stations in England, Australia, Japan, and the US. The estimated revenue from these sales will perhaps rise to a hundred thousand dollars.”

I didn’t touch a penny of this money. My nature, formed by the teachings of my father, is such that I had no urge to profit from those transactions. It wasn’t really because I feared being implicated in some underhanded activity, though it was obvious that this money was the outcome of the sweat and tears of the whole film crew and the Documentary Films Studio as well as my own devotion to the film and willingness to risk all, as I have related above.

I returned to Paris and Western Europe, remaining there until the beginning of July 1990.

What I sought was calm and peace of mind. It was truly bizarre that if the film had not succeeded and won a prize, I would have been jailed on my return to Vietnam, or else would have spent the remainder of my existence creeping furtively around Paris. But when the film had successfully escaped across the border and won a prize (in a festival with 256 films and only one golden and two silver awards—an affair no less risky than the adventures of Robinson Crusoe) the government kept the money, and no one knew what it was spent for.

It must be added that when the Union of Cinema Associations was dissolved as a result of a joint investigation by the Ministries of Culture, Public Security, and Finance, no one found out how the money had disappeared. Thus, going to prison was my own affair; and spending the money was the affair of those representing the government.

I say all this just to make everything transparent; otherwise, I feel quite at ease, for the goal I aimed at had been achieved. Our film had not been buried and beaten to death, but had had reached viewers elsewhere, in Europe, Asia, America, and Australia. And what was important in this was that the world could now regard Vietnam with greater respect, and human beings could be brought a bit closer together.

The letter the Vietnamese Association in France sent to the National Cinema Association of Vietnam with regard to selling rental rights for The Story of Kindness to foreign broadcasting stations.

It is possible that those colleagues of mine who have joined wholeheartedly in my dreams and efforts know little about these monetary affairs, so I hope they will understand that Trần Văn Thủy has always been consistent in his behavior.

I have spent my whole life as a filmmaker and as a person responsible for various film crews, but I have never once held money in order to enhance my financial security or in order to pocket it. I also thank all my colleagues who have undertaken double assignments to assist me in managing the budget in such a sincere and honest fashion. I also shall take this occasion to recount a little story so that my colleagues can understand the intensity of my fear of being involved with money.

In March, 1989, as part of a French film festival specializing in works of the “realist” school (cinéma du réel), The Story of Kindness was shown two times at the Pompidou Center in Paris. Hundreds of people who hoped to see it had to return home because they couldn’t get tickets.

In all the countries I have been to, one has to buy tickets to see documentary films; they are never shown gratis. In other words, the films must be good enough that people will be willing to reach into their wallets to buy the tickets.

News of The Story of Kindness in the newspaper Liberation.

How the ticket-sale money for The Story of Kindness was used I didn’t know; that was the business of the organizing committee and, though I wasn’t given any “envelope” as in Vietnam, I wasn’t concerned about the matter; I was concerned only about our films—and with the impression made by our films when they were shown in civilized societies. As for the impact of these showings of The Story of Kindness, the French newspapers had much to say.

Many spectators lingered a long time after the showings to talk and interact. Among these people, I suddenly found my attention drawn to a very cultivated yet taciturn, man. When everyone had gone their different ways, he came up to me and introduced himself:

“I am Michelle Nguyễn Thế Minh, a Jesuit priest. As part of the duties given me by my superiors, I’m supposed to concern myself with the culture of Vietnam. But after having seen your film today, I find that I’ve been at fault. I have understood nothing, and have not been able to do anything for Vietnam, as my superiors enjoined me to.

“Father,” I said, “You’ve surely been over here a long time?”

“I came here in 1952, when I was just a child.”

Then he told me what concerned him as a priest in a distant land, and told me how moved he was at the fate of the various personages in the film, and he didn’t hesitate to express his desire to help me by contributing a sum of money to support my artistic projects. I was moved, yet at the same time alert. After conversing for a while, we took down each others’ phone numbers and addresses, and I spoke humbly to him as follows:

“Father—the fact that so many people have welcomed my film at the Pompidou Center and that tens of thousands of people have watched it on the FR3 TV channel is already an immense honor for me. Thank you Father, and thank you for your generous feelings with regard to Vietnam; but I feel that perhaps you will allow this sum of money to be transferred to a place within Vietnam where your gesture would have a greater meaning, and serve a greater need.”

Mr. Michelle Nguyễn at once asked, “Then where shall we transfer the money? To what place in the realm of culture?”

Thinking swiftly, I said, “Father! Perhaps the place to begin with is the Thăng Long Private University which has just opened. I think we need to support private schools.”

He was pleased at this and asked, “And then if we wish to help a second place as well, what should it be?”

“Father, it should be the Vietnam Cinema Association. It’s a professional association that needs the assistance of others.

When I think the matter over now, I see I was merely improvising when I gave these answers. I introduced the Cinema Association only because I had many beloved and respected friends there. That’s all. Later the organizations belonging to the Union of Literary and Artistic Associations, including the Cinema Association, turned into “political professional associations.” If Mr. Michelle Nguyễn had learned later that the group I introduced him to was a government-run group, I don’t know what he would have thought of me.

After that I went many times to his church at 42 rue Grenelle. I went there for social functions and related church ceremonies, sharing meals with priests from all over the world who came to join these gatherings. The money Father Michelle transferred to Vietnam to assist the Thăng Long University and the Cinema Association was all cash, in American dollars.

A young friend from Vietnam who had come to France to study said to me, “You give that money to me—I’ll help you.”

“Help me do what?”

“I’ll just make one quick move, and in a single stroke the amount will be double what it was.”

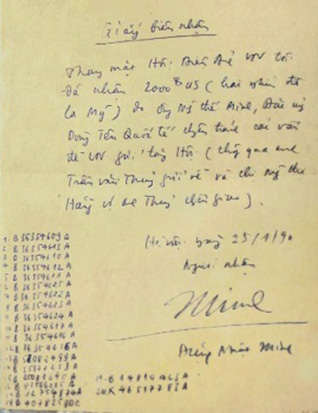

I at once sent the money back to Vietnam with the demand that the recipients make out receipts…

“How do you propose to do that?”

“I’ll order one container of used motorbikes (for shipment to Vietnam), then the money will be doubled (by the profits)!”

I thanked the young man, but I at once sent the money back to Vietnam with the demand that the recipients make out receipts showing clearly the serial numbers of each of the bills received, so as to prove that the money was not being diverted into winding paths and used for other things. I have held on to the receipts I got from Mme Hoàng Xuân Sinh and Mr Đặng Nhật Minh showing the serial number of each bill.

I hope my colleagues will understand that one reason I have survived until the present day is that I am honest and transparent. I acted in this way so as to avert later trouble, and steer clear of the slanders that are always ready to fall on our head. If I hadn’t acted this way, who knows that certain people might have thought I was getting money from “hostile forces”—then I would have been wretched!

Though I’ve been transparent in monetary matters, I haven’t been especially transparent in other “professional affairs”; in fact some people have even called me “Thủy the sorceror.”

I should relate as well that Father Michelle Nguyễn later returned to Vietnam after having been away ever since 1952. He said, “I made the decision to return after watching The Story of Kindness and meeting you in Paris.”

During the days he passed in Vietnam, Father Michelle was happy and excited; he liked and praised everything, even the street signs in Hanoi. I thought this a little strange, because Father Michelle had lived in civilized places, such as Rome and the Vatican City.

Thus one can see that beauty and ugliness, skill and clumsiness, and gaiety and sadness aren’t entirely due to the intrinsic qualities of things, but arise from the way they are viewed by each person.

Father Michelle went on excursions with my family, visiting different sites and enjoying Hanoi delicacies. He had us sit and pass time in a café near Ô Quan Chương (an old city gate of Hanoi). Throughout his stay in Vietnam, Father Michelle was happy as he had never been before—it is something that my family will also never forget.

Since we are talking about the element of money in my professional affairs, let me relate how I came to be accused of “taking films out of the country and selling their rental rights.”

During my many trips to Europe from the end of the 80s on, I witnessed a phenomenon that I couldn’t get out of my mind. This was the difficulty that second and third generation Vietnamese had in holding on to their traditional culture. The language, customs, and traditional festivals of Vietnam all came to seem very distant to these young people. It seemed to me that this was unlike what occurred in other overseas communities, such as those of the Chinese, the Indians, the Arabs, and the Jews. No matter where those people lived, or how many generations passed, their young people were always able to speak their mother tongue, were always steeped in their own culture, and were devoted to preserving it.

Being obsessed by this matter, on my return to Vietnam I made it the subject of discussions that I had with film director Đặng Nhật Minh, who at that time was General Secretary of the Vietnam Cinema Association, and with Ma Cường, who at that time was Director of the Central Documentary Film Studio. I asked permission to print copies of old documentary films on cultural themes, such as festivals, customs and historic sites, about twelve films altogether, so that when I returned to Europe I could show them to these young people and leave the films as a gift to them when I went back to Vietnam.

After I explained my idea and supplied a list of the films I intended to print copies of, Đặng Nhật Minh and Ma Cường gave me their support. I was also careful to discuss this matter with the makers of those films, and to ask their permission to proceed. They all agreed to my request. I used my own funds to purchase celluloid film and pay for the printing.

The technique of film reproduction in those days was very primitive. The (old and streaked) 35-millimeter film was put into a portable movie projector and shown on a screen that was in fact a dirty sheet of cloth the color of coconut milk. Anh Đỗ Khánh Toàn used a VHS camera to film the movies. When this was complete, the director of the film studio helped me by producing official documents requesting the customs authorities to let these films to be taken out of the country. The customs authorities allowed the films to go through, and I flew with them to West Germany, which was my first stop on a journey that lasted many days.

Due to the workload, I asked my superiors to give permission for the cameraman Đỗ Khánh Toàn to go to Europe and assist me. No sooner did anh Toàn set foot in the Frankfurt on Mainz station, than he related a piece of news to me that struck me like a thunderbolt. At home they were investigating me for “taking films out of the country and selling their rental rights.” Anh Toàn also informed me clearly that he had witnessed the General Director of the Vietnam Union of Cinema Associations send a person taking a case file for investigation to the Ministry of Public Security.

I was utterly disgusted, and with great bitterness threw the piles of cassette reels into a drawer that I swore never to open again. It had taken so much time and effort for us merely to get hold of those cassette reels!

But on reflection, it occurs to me that everything in life must have a limit, even goodness of heart and patriotism. How a person who stood at the very head of the film industry in Vietnam had actually been able to imagine that I had taken films with such a miserably low level of production quality to Europe in order to sell their rental rights!

People thought that I was greedy and motivated by money. The only person at home who came to my defense back then was the director Thanh An. He was the Deputy General Secretary of the Vietnam Cinema Association. With jovial humor he cracked, “If that fellow Thủy manages to sell such a bunch of lousy films, then we’ll have to decorate him as a hero when he returns!

And when I returned from Europe exactly one year later, many pairs of eyes were fixed curiously on me. I was called in to see anh Kim Đạo, the chief of inspection at the Documentary Film Studio. Chuckling, he handed me a piece of paper: “You keep this as a souvenir of what the General Director of the Union of Cinema Associations thought of you!” I unfolded the paper and read it. It was a handwritten note requesting anh Kim Đạo to investigate and make a report about my taking films out of the country.

I wish to add that when the General Director was a poor and obscure beginner with no position or power, he was a sociable and pleasant man. On one occasion, late at night, we had just left the villa of a high official and were peddling bicycles along Quán Thánh Street amid drizzling rain. He muttered, “In Russia it was logical for them to make such films as ‘Song of a Soldier,’ and ‘The Flying Cranes.’ What the hell is ‘revisionism’?” At that time he was still pained by life, just like me and everyone else.

But it was not just him, but quite often people in Vietnam are also like that. Once having a bit of position and power, they would behave haughty like a big shot, failing to realize that, in gaining this power, they have lost something far more precious.

In this connection I have an observation, which, right or wrong, is as follows; most of my colleagues love power and position, except for a few who skim lightly over such things, like anh Trần Vũ or anh Trần Trương in the feature films studio. Except for some people who have to get involved in administration due to the demands of their work or the confidence that their friends entrusting in them, the rest love power. Many people have received meticulous training at government expense, spending five to seven years pursuing specialized studies in foreign countries so as to obtain a degree in cinema, in spheres such as directing, technical work, or finance. At first they throw themselves enthusiastically into their professional work, but when they get promoted and gain some trifling rank or other—the chief of this or that—most of them forget entirely about their profession, as if it were trash. For them, their profession doesn’t amount to a hill of beans.

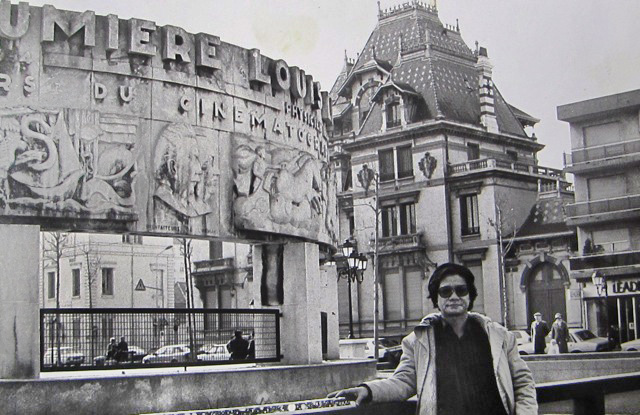

A temple dedicated to the Founders of Cinema: the museum of the Lumière Brothers in Lyon.

I think it’s not coincidental that from ancient times, we Vietnamese have had the custom of worshipping Professions, and the Creators of professions. It seems that the word “Profession” stands for something sacred, something spiritual that belongs to the realm of human integrity. It far transcends the world of objects made by clever hands.

Now let’s go back to the topic of money. If I were greedy for money, I would long ago have fallen into some deadly trap. When I begin a project or embark on a film, it is never because of the money I might gain from it, or for fame, or to please somebody; and I absolutely do not do it to obtain a promotion. I take the pursuit of my profession seriously, and when I engage in professional work I focus on one thing only: will it be useful? Will it make viewers happy?

On reflection, I want to say to my young colleagues, the documentary film-makers who are now just about the age I was fifty years ago, that: when you begin making a film, try to express what you think, what deeply concerns you, and what you think will be useful to society, in a sincere and honest manner.

People say that the word tiền (money) is often conjoined with the word bạc (silver, or “ingratitude”). This principle is as old as the earth, but I grow sad when I reflect that today, money makes people far more ungrateful and wicked than in former times.

Order In Whose Eyes from the University of Massachusetts Press, or from Amazon.

All text and images are © 2023, Trần Văn Thủy, all rights reserved. Written permission is required for any use.