Chapter Twenty-One

My friend Diane took me up the coast of California in her own car. This was only one of hundreds of trips that have taken in the course of my wandering existence, but it is nevertheless an unforgettable memory.

Both before and after that trip, I had the mind-set of an observer. If you want to appreciate and absorb your surroundings, you shouldn’t travel by plane, but should rather “crawl” on the earth’s surface. And you can easily imagine how tired a person like me must have grown of climbing up and down stairs leading to airplanes after having conducted who knows how many viewings and discussions of my films in more than thirty different universities in the US.

I have referred a lot to Diane in our talks. She sought me out and came to know me on the web. She was an anthropologist who could speak Vietnamese, and she was especially concerned with the effects on the Vietnamese population of Agent Orange. She had been to Vietnam many times, had stayed there many months, and was closely acquainted with many people doing research on Vietnam. Once she wished to go to Thái Bình, a place with many victims of Agent Orange, but was prevented from going there because uprisings were taking place in Thái Bình at that time. She was looking for ways to help the unfortunate, but obstacles were put in her way.

At that time, she also took time to translate, without remuneration, the script of our film A Story From the Corner of a Park, so that it could be shown in the US and other countries. In a very lucky and coincidental manner, the film was shown with great success at a conference on agent orange that was held at Riverside College in California in May, 2009. Dianne and I were both present at that conference. I remember a scene (that can also be consulted on videotape) that occurred during the discussion that followed the showing: A young man of Vietnamese descent sat up and said, with eager intensity:

“This is a propaganda film.”

Gaily, I answered as follows:

Yes, my dear young man! You have spoken very correctly! This is precisely a propaganda film. But please, for my sake, reflect a bit. What situation in the life can be explained to all without recourse to propaganda? Propaganda exists in this land of America in greater quantity than anywhere else. Advertisements for goods are the purest form of propaganda, and presidential campaigns are another form of propaganda. The problem lies purely in what you are propagandizing for, truth or falsehood, goodness or evil…

The audience consisted almost entirely of research scholars, teachers, journalists, and former military men, so it was easy for them to sympathize with this point of view.

I remember that before she left Vietnam to return to the US, Diane gave me a sum of money to help a child living in poverty so that he could continue learning how to fix bikes and motorcycles, and thus have a means of subsistence in the future. She instructed me not to give him the whole sum at once, lest he spend it all right away.

In Hanoi, she formed similar relationships with many poor children.

In the world of film, the west coast of the US is a place of might and mystery. I had read about the region a great deal in novels, but Diane related many curious and interesting details to me concerning the places that were whizzing by the mirrors of our car. It seemed that today, the ocean waves were bigger, and the vault of the sky was higher. The ocean waves towered up, the forests were dense with trees, and the ten-lane highway went on forever.

I began to think of the destiny that had pushed me along in my life as a film-maker, with its precarious ups and downs, its moments of glory and ignominy, a destiny that had at last led me to see strange lands, lands connected with the ocean, with lakes, and with water—in other words with Thủy, the name bestowed on me by my parents, which means “water,” and is one of the five elements in traditional Chinese cosmology.

During my period of study in Russia, I had had the opportunity to pay eight visits to Lake Baikal, the largest fresh-water body of water in the world; and once I had stayed by Lake Baikal for several months you make a film.

From the top of a hill in the Marseilles harbor I had been able to look down on the Mediterranean Sea; and I had seen the Black Sea from the city of Sochi, and I had gazed at the Baltic from Hamburg, and the North Sea from St. Petersburg.

I had seen the oceans from every direction. I saw the Atlantic from the east when I was in Nantes; and I have gazed at it also from the feet of the Statue of Liberty, and from Massachusetts. I have looked at the eastern Pacific Ocean from Los Angeles and San Francisco, and have seen the western side from Japan. I have seen the southern Pacific from Sydney and Melbourne. I have seen the Caribbean Sea from Florida and the Manche Sea from Deauville. I have seen the sea surrounding England from Manchester and London, and have looked at the Adriatic Sea from Milan, Rome, and Venice.

I have also had occasion to take in the sight of Lake Tahoe, a beautiful and mysterious Lake, as if belonging to some historical legend, a famous higher-than sea level lake lying between California and Nevada.

For gifted, powerful, and wealthy people, traveling around and seeing all these sights is an ordinary affair; but for a simple bloke like me, who had lived with people in primitive tribes who went about half naked and ate tubers and beasts of the forest, and who for ten years, from age twenty to age thirty, had no more cherished hope than to be able to eat a square meal and walk on a level road, this was truly like a dream in the midst of human existence. Many times in my life I had declined so much in health as to be almost comatose and close to death… I had truly never dreamed that I would be able to gaze at high skies and wide vistas in this fashion.

And aside from all this, these journeys were of great benefit to a documentary filmmaker like me.

When we got to Portland, it was dark already. We stayed there for two days. Each morning I went for a walk in the neighborhood to get some exercise, and noticed that Diane’s house and others nearby all lay in wooded areas. As had been planned, she brought me here to hold discussions, show films, and meet people at two universities in the area during those two days. The day after that, we continued our journey, until we reached Seattle, the capital of the state of Washington in the extreme northwestern corner of the US, near Canada.

Seattle was the place where Diane worked, and was also the place that had invited me, Wayne Karlin, and Trương Vũ to give lectures. Many enjoyable and diverting things occurred there.

I got to meet Ms. Rosemary there, a woman who spoke Vietnamese like a native; her Vietnamese name was Thảo. Her husband was a man of Vietnamese ancestry named Hiếu. Rosemary astonished all the Vietnamese she met with her thorough and deep familiarity with Vietnamese language and culture. When I was helped by my friends to publish If You Go To the Ends of All the Seas, she, together with Thái Tuyết Quân and Diane Fox translated Wayne Karlin’s contribution without asking for any compensation.

The chairman of the Southeast Asian Studies Department in Seattle was a German man who spoke excellent Vietnamese and knew a great many humorous stories concerning Vietnam.

In Seattle, I engaged in three discussions. In one of them, Wayne Karlin and Trương Vũ also took part. I feel that that discussion created an especially strong impression among American teachers, students, and former military men.

My business with Diane in Seattle and on the west coast came to a conclusion. We parted with reluctance. She came to the hotel where I was staying and gave me a large, expensive book printed in beautiful colors on the history and architecture of the University in Seattle, and drove me to the airport to fly back to the east coast, where I was staying in the house of a friend in Boston, the place I stayed at more than any other whenever I came to the US to carry on my work.

But the event that moved me most during my visit to Seattle was the following:.

After one of the discussion sessions at the university in Seattle, many members of the audience stayed around afterward to converse with the gilm-maker (me). Among them a wife and husband named Thanh and Kiệt waited until they could successfully invite me to their house, where they received me very warmly.

The rooms in their house were tidy and tastefully arranged. I cast my eyes around, looking at everything (a very ordinary thing to do among us Vietnamese, but not too polite in the West), and saw on the wall a handsomely framed photograph behind glass, right in the middle of which there sat an elderly, white-haired woman in formal dress, while behind her stood five youths dressed in suits and wearing glasses. Their faces all looked alike, and they were close to one another in age, so it was not possible to tell who was older and who younger.

“So where is your father?” I asked Kiệt.

Kiệt pointed to a small black and white photo carefully hung next to the larger photo.

“This is my father!”

“So where is your father? Is he in good health?”

“My father is no longer living.”

“Oh, I’m sorry. Where did he die?” (a question very much in the style of Vietnam in former days).

Kiệt hesitated a few seconds and then said, “My father died in a reeducation camp.”

I was stunned! The family of a man whose father had died in a communist prison was greeting a person from communist Vietnam with cordial warmth!

Kiệt said, “It has been a great honor for us today that you accepted our invitation to visit us. In a short while, I shall ask your permission to take Thanh to a hospital to give birth. She has already widened by two centimeters, my dear sir!”

I was very ashamed that I didn’t know what “widened by two centimeters” meant, but Heaven was kind to me and arranged matters so that I didn’t ask further questions, as I had before.

Good grief! The wife was about to give birth, but she and her husband still invited me to come and pass time with them at their house!

Two days later, after I had returned to Boston, I received an email from Thanh and Kiệt saying that their baby was born, and was such-and-such a length and such-and-such a weight. Then they presented me with three different names, and asked me to select one of them for trheir child!

I was immensely moved. How could life deliver me into such unimaginably strange situations? And could I ever get over my shame at being a Vietnamese communist?

Could it be that Diane Fox formed the intention of organizing this visit to a number of universities on the west coast because she wished to build a bridge of peace between Vietnam and the US?

Could it be that Diane formed the intention of organizing this visit to a number of universities on the west coast because she wished to build a bridge of peace between Vietnam and the US? But surely she could never have known that there would be some Vietnamese spectators—like Thanh and Kiệt—who would show me such astonishing generosity and respect.

This was an example of “reconciliation,” a reconciliation much more difficult to achieve than that between the Vietnamese and the Americans.

My encounter with Lý Kiệt and Thanh Xuân remained ever-present in my thoughts for a long time. This was because people who come from within Vietnam to the US do not meet with this kind of fellow feeling at all times and in all places. Once in Europe, in 1989, a person called me a “cultural lackey,” and in the United States I was threatened a couple of times when I went to universities to show films and hold discussions, and was called “a communist cultural guerilla fighter.” At times I grew disgusted and weary at these geographical and ideological divisions. Once, while among people, some close and some distant, who were hurling abuse at me, I wasn’t able to preserve my calm, and I spoke very bluntly to them: “Don’t blame me, gentlemen, and don’t blame Vietnamese society for the many evils that are now taking place in the country. There are many reasons for these evils, but the chief reason lies with… you yourselves! You gentlemen lost the war and ran away, and you left behind a land as beautiful as embroidered silk to be trampled out of shape by the Vietnamese communists. The US pumped you up with huge quantities of assistance, but you said, ‘If you give us seven hundred million, we’ll give you seven hundred million’s worth of fighting, and if you give us three hundred million, we’ll give you three hundred million’s worth of fighting.’ Later on, a rumor arose that I wasn’t any sort of film director at all, but was just a cadre charged with spreading propaganda. And so I had to worry about protecting myself from reprisals when I returned to the country! It was a heavy burden to bear.

But among these circumstances, there were also quite a few occasions when I was the recipient of sympathy and encouragement of others. These included the intellectuals who opened their doors wide to me with generous cordiality, the people who helped me write If You Go To the End of All the Seas, the people who took me to see all the sights in the US, such as Disneyland, Las Vegas, Hollywood, San Francisco Bay, New York City Harbor, and all the sights of Washington DC. Many of these friends and their families entertained me in their homes for as long as a week when my schedule brought me to their states. They were all warm and friendly to me, “a country bumpkin come to the provincial capital”—this moved me very much.

[The remaining parts of this chapter are all omitted in the English edition]

There is a further story that has given me uncertainty for a long time—I have had a hard time deciding whether I should relate it here or not—because writing it out might create trouble for people who treated me well. But perhaps circumstances have by now altered for the better, so I shall not ask to be forgiven for telling the story.

At the beginning of 2003, the University of California at Berkeley invited me to there to hold films and hold discussions. At the time I was staying in the home of Hoàng Khởi Phòng in Westminster. On that day, he took me out to the inter-city bus station in front of the Phước Lộc Thọ shopping center so as to board a “Hoàng Company” bus bound for San José, where thye university was located. The bus was of the best quality, and the passengers were all Vietnamese who talked with each other in Vietnamese. The old ladies chewed betel and told stories about their families and children. Cải lương operas were shown throughout the trip on a TV screen in front of the bus. The driver and the bus steward were lively and efficient, yelling out instructions, just as they do in the inter-city busses of southwest Vietnam.

And this too was the western region—the only difference being that it was in the US. The trip started at 9:40 am, and the bus steward distributed a meat sandwich, a bottle of water, and a plate of gelatin to each passenger. The bus arrived in San José at 4:15 p.m.

I noticed that the bus steward (I didn’t know if he was actually the steward or just a person in the family of the chief of the company) was in charge of everything in the bus, from the reception of passengers to the selling of tickets and collection of money. Since I was a stranger in the bus and didn’t want to trouble anyone in the bus with an awareness that I was a “Vietnamese communist,” I sat close to a window, gazed at the scenery, and engaged no one in conversation. The bus conductor passed right by me several dozen times, but never sold me a ticket or asked me any questions. As the afternoon wore on and the bus drew near to San José, I said to him, “Please let me buy a ticket!”

“It’s not necessary. You still have the return trip to take—there’s no hurry. I wish you a delightful time doing your business at the school. When you come back, ride in my bus, okay?”

Having said this, he disappeared.

A person was there to meet me. Ms. Thấm Vân was sent by UC-Berkeley for that purpose. After a few days of going to classes, conducting far-flung discussions, and making an excursion to see the Golden Gate Bridge of San Francisco, she took me back to the Hoàng bus company at the intercity bus station.

On the ride back to Westminster, I again got to appreciate the flavor of an “inter-city bus in the southwest,” to listen to the speech of my compatriots, to listen to cải lương opera, and to old ladies recounting the faults of their children… And I saw that the bus steward seemed to be ignoring me on purpose as he sold tickets and counted money. I began to suspect that Hoàng Khởi Phong or UC-Berkeley had purchased the tickets for me in advance.

Late in the afternoon, as we drew near our destination, I asked the bus steward to let me pay for my round-trip journey. The young man looked straight in my face and, with a warm smile, spoke some words that I will never forget:

“My good sir! You are Mr. Thủy, Trần Văn Thủy, correct? I recognized you right from the moment that Mr. Hoàng Khởi Phong saw you off at the bus station. You have given us the great pleasure of being in a position to take you on this trip. Di you know how delighted we are? The world is a small place indeed—for it has given me a chance to meet you. Look around—there is plenty of space on this bus, and there are plenty of empty seats—the seats would still be there, whether or not you took the trip.

And then the young man told me enthusiastically how, when he left Vietnam (I don’t know whether as a “humanitarian policy” emigré or as a boat-person), he had stuffed two DVDs, one of Hanoi in Whose Eyes and one of The Story of Kindness, into his underwear to bring to the US. After arriving there, he made hundreds of copies to distribute to everyone…

My eyes grew wet with tears. I said that UC-Berkeley had given me money for the trip—if he didn’t take it, then I wouldn’t be able to use it either. And I said that if he knew Hoàng Khởi Phong, then we would surely meet again.

But no matter what I said, the young man would still not accept any money. When I came back to Hoàng Khởi Phong’s house and told him the story, he laughed out loud. Then he told me that many friends had contributed funds to print the book If You Go To the Ends of All the Seas. He didn’t say anything about people particularly close to me, but he mentioned that one of the contributors had been Hoàng’s bus company. I don’t know whether it was the chief of the company or the young bus steward who brought the money to Hoàng Khởi Phong, saying that it was to help print the book. But whoever it was told Hoàng not to mention the matter to anybody, for fear that the company would suffer a boycott on account of being pro-communist.

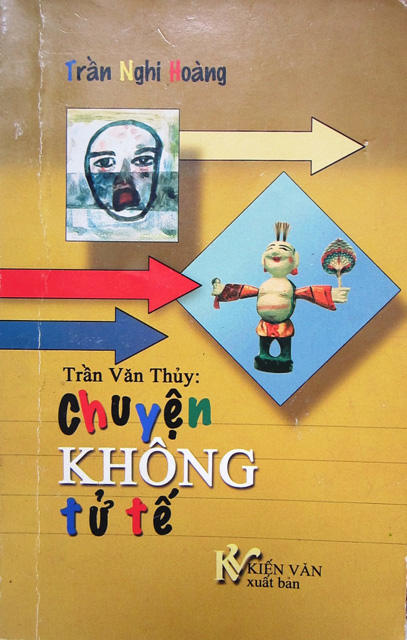

The cover of A Story of Unkindness by Trần Văn Thủy, published by Kiến Văn in Virginia, October 2004.

That the young man (if that is who it was) was worried about this was not without reason.

In the book Trần Văn Thủy, A Story of Unkindness (published by Kiến Văn, Virgina, Oct. 2004), the following passages occur:

Page 12: The party must be credited with building Trần Văn Thủy into the phenomenon that he now is. Don’t say that I’m a suspicious person! Do me the favor of providing a single example of a “courageous” person who dares to tell the truth under the Vietnamese communist regime who has not been crushed by the heaviest of punishments…

Page 32: It is clear that Trần Văn Thủy has always carried in his head the mind of a Vietnamese communist…

Page 52: Who is Trần Văn Thủy? A pleasure seeker? A position seeker? All I know for sure is that Trần Văn Thủy is a cultural cadre of the government and the party of the Vietnamese communists who is carrying out a mission…

Alas for the Vietnamese people—it is the same everywhere. Wherever they live, there are people among them who like to set forth their “political stance,” and who think that slandering and destroying each other is the most important thing in the world…

Order In Whose Eyes from the University of Massachusetts Press, or from Amazon.

All text and images are © 2023, Trần Văn Thủy, all rights reserved. Written permission is required for any use.