Chapter Twenty-Three

When the thirtieth anniversary of Mỹ Lai massacre approached (March 1968–March 1998), stirring memories of the victims of the event, Thủy felt that he had to make a documentary film on that topic.

But that was the sum total of what had occurred to him! He didn’t have an outline or a script. Even what was in the mind of the director amounted to an absolute zero!

Nevertheless, Nguyễn Văn Nhân, the director of the film studio, and Lê Mạnh Thích the assistant director agreed to supply all that was necessary for Thủy to make the film; they belived that as long as his team did it, the film would be okay.

From the newspaper Lao Động (Labor), Thủy learned that two Americans with a direct relationship to the event named Hugh Thompson and Larry Colburne were coming to Vietnam and would go to Mỹ Lai.

Just as Thủy was taking in this information, his son Thăng came to speak with his father:

“It looks like some Americans are staying at a place on Hàng Bạc Street.”

A most unexpected piece of news—but entirely mysterious. Thủ made his way to Hàng Bạc Street.

Yes, there was a hotel there…

“My good sir, are there some Americans staying at your hotel?”

“Yes indeed.”

“Please call one of them down so I can meet him a bit, okay?

“Who do you want to meet? What’s his name?

“Any of them will do.”

Nothing could have been stranger!

So a big lumbering American came down and the two exchanged a few words. In a voice as cavernous as if it came from the depths of hell, the American said that would also be going to Mỹ Lai. That was all there was too it. He gave Thủy the telephone number of a Vietnamese friend of his named Phan Văn Đỗ (later on anh Đỗ made many contributions to the making of the film.)

On returning home, Thủy phoned anh Đỗ and invited him to his house to have dinner with him that evening together with some of his film-making associates.

The trays of food were laid out, making a fine display, but the agreed on time came and no one appeared.

The phone rang. The plan wasn’t going to work!

“Anh Thủy, I’ve asked another person to come along—is that okay?”

“Bring along as many as you like—just come and enjoy yourself.”

A short while later, anh Đỗ materialized between the gates to his house, which had been thrown open, and standing next to him was the lumbering American whom Thủy had met in the morning. It was as if arranged by fate.

“Hi, I’m Mike Boehm.”

Beer flowed freely, and Hằng, the lady of the house Gaily offered everyone all the delicacies of Hanoi. The newcomers to the house chatted as naturally as they had been lifelong friends of the hosts.

In a leisurely fashion, Mike recounted that he had connection at all with the Mỹ Lai affair—when it occurred he was working for an army unit in Bình Dương that was not involved in fighting. Nevertheless, from the time that the Mỹ Lai massacre occurred and stunned the world, Mike felt as if Vietnam were a piece of his own flesh and that the massacre had changed his whole life. Everywhere he went, and at all moments, his thoughts were painfully involved with Vietnam.

“Do you have a family yet?”

“Oh, I had a young lady friend—she was a fabulous girl, and I loved her very much. I was very grateful to her for allowing me to live a happy life and for enabling me to bring happiness to her in return.

Every year I would go to Vietnam to visit Mỹ Lai on these occasions, and each time she would see me off at the airport.

Once, before I got on the plane, she said to me, “Mike, please answer me very clearly. If you had to choose between me and Vietnam, which would you choose?”

I was taken by surprise, She repeated her question. I said, “Oh good heavens! I love Vietnam and I love you! Don’t force me to make such a choice! Don’t pursue me into a blind alley!” But she was still eager to know. “Choose! I need this.”

After a prolonged silence, I said, “If you force me to choose, then I must choose Vietnam.”

We both wept, and then she turned her back on me and slowly went out the exit.

Having heard the story up to that point, everyone grew silent, and no one wanted to eat or drink anymore.

Moments later Thủy said,

“If you go living in this fashion, it will be too sad; you must be happier; you must do something to gain happiness to live, such as sports or music… the war’s been over for a long time.”

“ I do have something—I play the violin.”

“Oh, that’s wonderful—let me find an instrument for you!”

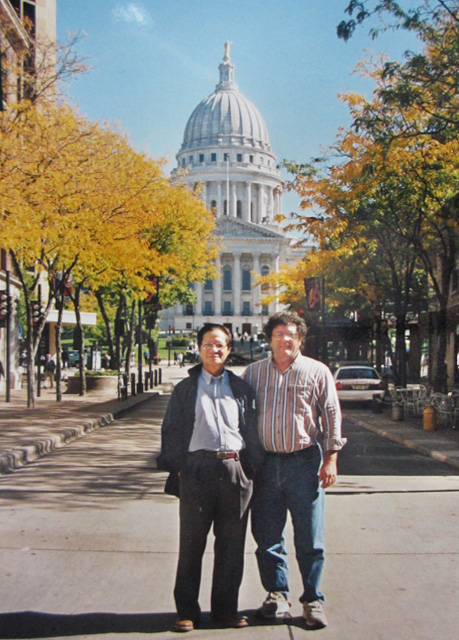

Every year I go to Mỹ Lai and stand with the violin in front of the graves and play it for the departed to hear. (pictured, Mike Boehm)

“I have one already. Wherever I go, I take it with me. Every year I go to Mỹ Lai and stand with the violin in front of the graves and play it for the departed to hear. I only play two tunes, “Prayer,” and “Farewell to Arms.”

Thủy leapt up, raised his hands to the sky, and exclaimed,

“I have a film now!

And so they went together to Mỹ Lai.

It seemed that all would go smoothly until a barrier huge as a mountain loomed in front of them. The gigantic American TV network CBS had signed a contract with the provincial government giving CBS the exclusive right to convey images of the key parts of the commemoration ceremony to all parts of the world! And they had deployed a whole squadron of “troops and generals” to stand guard at the spot!

So were his hands tied?

Having the talent to make an excellent film is in fact… not enough!

He would also have to know how to insinuate a camera into the scene to shoot the crucial segments when he was barred from doing so, and once he had the scenes, he would have to know how to get them to viewers when doing so was prohibited.

Such techniques might be called… witchcraft! They can’t be learned at a school.

And so The Sound of a Violin at Mỹ Lai won the Golden Crane Award at the 43rd Pacific Asia Film Festival held in Bangkok in 1999!

The Sound of a Violin at Mỹ Lai won the Golden Crane Award at the 43rd Pacific Asia Film Festival held in Bangkok in 1999.

After that arrangements were made to show the film in the solemn atmosphere of the National Movie Center. The auditorium held five hundred seats, half of which held Vietnamese spectators, and half Americans and other foreigners invited to the event. The American ambassador made a moving speech.

The film company presented Mike with an enormous canister holding the entire movie on 35-millimeter celluloid film. Mike took the film and mounted it on his jeep, and carried it everywhere he went in the US.

Once Thủy went to Madison, Wisconsin to visit Mike, and Mike invited him into his jeep to go for a ride. Before they went into the country, Mike stopped in the city and carried some armfuls of bottled water, bread, and canned meat into the car. The places he went to were all street stalls where he could borrow goods from his friends—he didn’t have a cent in his pocket!

Mike drove Thủy into the countryside in a region close to freezing Canada. He went all the way to a place where, as a child, he had drilled a hole in the ice on a river to get some fish. At the time, he said, he was just over ten. Somehow, he lost his footing and fell into the hole—he still doesn’t remember how he got up again. Such accidents are often fatal, because the current underneath the ice carries you off, so that you can no longer find the hole and go up again… and in addition the water is freezing cold, your eyes can see nothing, and your limbs lose feeling and the power of movement.

Mike also brought Thủy out to a dam where, as a child, he would go to sleep through the night because he had been scolded by his father.

Loving Vietnam to an astonishing degree, Mike lived by himself in a dark, run-down apartment with nothing in it of any interest. On the wall there was a document testifying that he was a member of “The Women’s Association of Quảng Ngãi.”

…the people inside the building were all ugly characters, with nothing admirable about them. (They were standing in front of the legislative building in some midwestern state. The caption gives Mike Boem’s assessment of the state representatives and senators who worked in the building.)

But there was nothing about his own country that Mike liked. When he saw Thủy taking a picture of the town hall in Madison, a beautiful building reminiscent of the legislative assembly halls in Washington DC, Mike asked him what the point of taking the picture was—the people inside the building were all ugly characters, with nothing admirable about them. When Thủy bought an American flag as a souvenir, Mike also found it difficult to approve: “Those fifty stars are not fifty states, but fifty monopolies that are tearing the United States apart!”

Mike kept living in that random, simple manner, saving his pennies so that he could have money to go to Vietnam and engage in charitable activities.

Recalling these things, Thủy felt sorry for Mike, and wished that he could forget about the past and live for himself.

To have been so sad and disillusioned was enough…

The Sound of a Violin at Mỹ Lại was finished, and won a big prize, but, as people often observe, there were still some related circumstances of interest that didn’t appear in the film itself.

The film crew went on the road without having received any decision from the Cinema Department—could that be why the film wasn’t censored? The film was made on a “behead-first-report-afterward” basis, and then when the chiefs were invited to watch it, they didn’t!

Nguyễn Văn Nhân, the director of the film studio, sent a direct invitation to Nguyễn Khoa Điểm, the head of the Department of Cultural Affairs, to see the film—simply to see it, censoring it not was another matter. At first Mr. Điểm thought it was only a film script; when he learned that it was a completed film he came down to see it on a Sunday afternoon, alone, with a driver.

When he had finished watching the film, his eyes were red. He said,

“The people of Quảng Ngãi thank you gentlemen, and the souls of all those unlucky victims thank you.”

He had the people in the Cultural Affairs Department watch the film, make many copies of it, distribute it for public viewing, and send it out to film festivals across the world.

And thus, it was a week later when the Cultural affairs chief came down to watch the film, and when he subsequently heard that the Executive Board of the 43rd Pacific Asia Film Festival in Thailand had announced that the film had won the Golden Award, the department chief was overjoyed, while the deputy chief was worried…

As I sat and talked about Sound of a Violin at Mỹ Lại, I had an opportunity to recall some of my colleagues.

First of all, I’d like to say a few words about Nguyễn Văn Nhân and Lê Mạnh Thích, two people who believed in us and gave their wholehearted support to the film. Because there was little time left to do the project, we had no film script, and hadn’t obtained a decision from the Cultural Affairs Department, or a decision with regard to personnel, or an estimated budget… but in spite of this, those two gentlemen still supplied us with movie cameras, money, and letters of introduction, and we set out for Quảng Ngãi. I have to say that these to people were men of feeling, devoted to their work and to their colleagues. We are grateful from the bottom of our hearts to such people. When I meet with difficulties and obstacles in my work, I am sometimes discouraged, but when I think of the bonds of feeling between us, I try harder. Thus it would appear that when people believe in each other, life can be more toilsome than ever.

And then there were my colleagues Hồ Trí Phổ, Vương Khánh Luông, Lê Huy Hòa, Đặng Trần Anh, Phan Minh Hưưng, who dealt with technical matters, film printing, economics, and finance. Each of them made noteworthy contributions.

Before he accepted my invitation to work with me, anh Hồ Trí Phổ was working in a studio that made scientific films, that also belonged to our company.

He was a person equally able to think, write, and act. I often said that he was like a kitchen cleaver; whatever business came to him, he did it, and did it well. When we worked together, he would on his own initiative plan out everything the film crew had to do in a detailed and attentive manner, including highly specialized matters, and the arrangement of such things as meals and lodging. We would surely have more excellent films if a person of his vast experience, so full of the stuff of life, so resourceful, and with so many latent abilities had been methodically trained. Thinking of Hồ Trí Phổ I feel intense regret that the film studio failed to assess him at his true value, and did not make a fitting use of his gifts and abilities. Nevertheless, he made many contributions to three films of ours: The Story of Kindness, A Story From the Corner of a Park, and The Sound of a Violin at Mỹ Lai.

When I invited Vương Khanh Luông to be my cameraman for The Sound of a Violin at Mỹ Lai, I had confidence in his competence and care, his ability to capture arresting images, and his years of experience as a news photographer. Luông had created many filmed interviews, and had accompanied many prominent personages on their trips to meet leaders of other countries. He followed in the footsteps of the news photographer Phan Trọng Quỳ; both he and Quỳ were skilled practitioners, experts in the art of capturing scenes that occur only once, even only in a single instant—an art that not just any news photographer can lay claim to.

Later on, Vương Khanh Luông made many documentary films in which he was the principal director. Those documentary films were very genuine in content, very dramatic, and attractively structured.

Among the various cameramen who have worked with me, there was also Nguyễn Như Vũ. He made many films and accumulated many memories both before and after he worked with me on A Story From the Corner of a Park. The directors of the studio, and his colleagues as well, valued him very much. He was peaceful and taciturn by nature—as was the case with his father, the cameraman Nguyễn Như Ái. Vũ was truly in love with his profession, knew how to listen, and also had views concerning the political aspects of his work. I always felt totally at ease when I worked with Vũ.

When I made The Story of Kindness, it was not by chance alone that I invited Lê Văn Long to be my chief cameraman. Among the cameramen working for the documentary film studio at that time, Long was not especially skilled or well-known. But when I began that project, it seemed to me that The Story of Kindness would at times require daring, and the capacity to skim quickly over situations, not just care and competence. I felt that Long had that quality; he was not concerned about face, or about the impression he made on others; he liked to speak truthfully and directly, and was willing to take risks. This impression was greatly strengthened later when I reflected that if someone else had been my cameraman for The Story of Kindness, the film would perhaps have lacked he long episode dealing with former days—the episode in the boyhood of the future cameraman in which he is put in charge of a herd of ducks, crawls into a hut to sleep, receives a black mark in his record, and then had a fine mathematics teacher who later became a vegetable vender… The attractiveness and usefulness of Long lay in these things.

Twenty years ago I invited the cameraman Đỗ Khánh Toàn to be my main cameraman in the film “A Spiritual Realm.” Like nearly all my films, it was made with 35-millimeter celluloid film. We traveled throughout Vietnam to make the film, spending the longest time in Huế. Due to this, the scenes in the film were very varied in character. He did his work very painstakingly, and was careful in arranging the details of every scene, never showing any sign of weariness. Since he was trained in the Democratic Republic of Germany, he was accustomed to doing his work in a very “western” manner; and it was perhaps for this reason that in 1989 I invited him to work with me on a long film shot in western Europe, including Germany, France, Italy, England, and Belgium. Đỗ Khánh Toàn had a way of living and working that was easy to venerate, for he was always sincere and selfless, and placed weight on the bonds of obligation.

I also have indelible memories of two sound engineers, Mai Thế Song and Lê Huy Hòa, who in former days belonged to the Central Documentary Film Studio. I have long held very clear ideas about the use of sound in my profession, and especially in documentary films with modern subjects. I have spoken about this as well with my younger colleagues and students, both in Vietnam and in other countries. Sound is really able to make a film come alive, and endow it with truth and seductive power. I don’t lie when I say that sound may account for fifty per cent of the soul and value of a film. But it is very important to have Modern sound equipment and a skilled sound engineer with equipment especially adapted for films. Mai Thế Song and Lê Huy Hòa were people of that sort, and contributed more than a little to the success of films made by the Central Documentary Film Studio, which included projects in which I participated. They were both people who had received methodical training and who loved their profession. It should also be noted that dealing with sound in films shot with celluloid is far more complex than integrating sound with videotaped films.

My experience with these two gentlemen has made me reflect that when you work with colleagues of such stature, you have to ask yourself if your own contributions are worthy to be matched with theirs.

And, in a professional spirit, I would like to draw the attention of younger directors to the fact that films are products made by teams of people working together; they are products of the pooled intelligence and achievements of these teams. A film director is like an orchestral conductor; He must know, respect, and understand the people who make up his band before he can exploit their talent and intellect.

In the period when A Barbarian of modern times was filmed.

I want to say a few words to express my gratitude to Nguyễn Sĩ Chung. He studied in the Vietnamese Film School with me back in 1965, and later studied with me in the Soviet Union in the 1970s. Then he returned to Vietnam and worked along with me in the documentary film studio until he retired. Chung’s main profession was script writing, but later he aso directed many films. His film The Countryside, which he made in 2001, won a Golden Award in the Asia Pacific Film Festival in Jakarta. Together with me and some other colleagues, including the cameraman To Thư and the sound engineer Cao Huy, Chung made a film in the Soviet Union in 1986. Chung had a rich fund of experiences in his life and professional work, and there was nothing that we didn’t recount to each other. Then, from 2009 to 2011, Chung worked with me, Phung Lê Anh Minh, and Nguyễn Sĩ Khoa—his youngest son—on the film Songs Resounding for a Thousand Years. Before that, I had worked with his eldest son Nguyễn Sĩ Bằng on a four-part film concerned with the early journalist, translator and activist, Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh entitled A Barbarian of Modern Times.

This friend of mine is a modest man who knows, much, says little, and shares his feelings in a calm, composed manner, so he is much cherished by his friends, and by… women.

I can’t refer to all the colleagues whom I value; I only wish to add that I am deeply conscious of the fact that it is only due to my association with all these dedicated and talented people that I have been able to make films that have been enthusiastically received within the country and elsewhere…

When we finished making the film, The Sound of a Violin at Mỹ Lai in Quảng Ngãi, the members of my team felt provisionally satisfied with the work they had done, especially since the film won the Gold Award in the Asia Pacific Film Festival. I say “provisionally,” because the film could have been better, and would have gone further, if we had been given permission to develop the topic as we originally planned.

There were at least three episodes in the film that we had to omit, as follows:

Episode 1: Thirty years after the massacre (in 1998) on the occasion of the memorial observances, the Americans who returned to the scene wanted to find the child (whose name was Đỗ Ba) who was rescued from a pile of corpses, to see what the boy’s life was like now, but the young fellow was… in prison for theft. This was certainly a joke of fate, if not a matter for shame. If this detail had been related in the film, it would have made even the most insensitive viewers see how heavily the word “liberation” had been misapplied. All of us in the film crew, and the journalists covering the event also, were very eager to find some way for Đỗ Ba to be let out of prison, so he meet his benefactors, but this prved to be impossible; our hands were tied. It was a bitter disappointment.

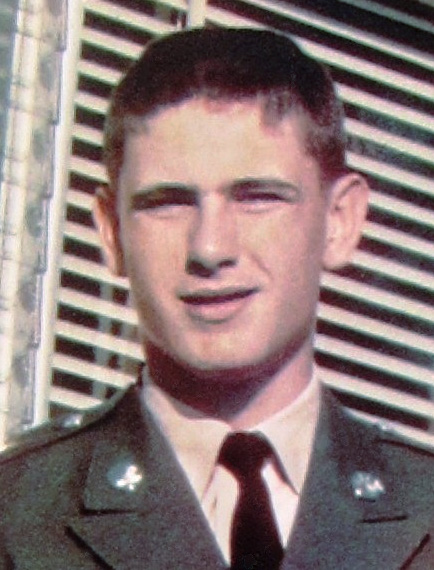

Pilot Glenn Andreotta, the person who noticed a body still moving… (photo sent to Trần Văn Thủy by Glenn’s family).

Episode 2: The pilot Glenn Andreotta, the person who, having noticed a body still moving, landed his helicopter and crawled into the pile of corpses and dragged Đỗ Ba out, covered from head to foot with blood, and carried him by helicopter to the Quảng Ngãi hospital.

A few weeks after the boy’s rescue, Andreotta’s helicopter was shot down, and he was killed, just like the victims at Mỹ Lai. Andreotta was the eldest son in a middle-class family. War is like that.

The squadron chief Hugh Thompson, the man who couldn’t be deterred from aiming his gun at a group of American soldiers, and was prepared to fire at them if they continued slaughtering innocent people, died in the United States only a few years after the memorial observance.

When the machine gunner Lawrence Colburn returned to the US after the war, he went into a period of personal decline and disgust with life, in which he became addicted to drugs, a state from which he couldn’t extricate himself.

With these details, viewers could have had a deeper experience and could have reflected more deeply on the meaning of the word “war.”

Episode 3: Another important detail that had to be omitted was a description of the life and destiny of Mike Boehm, the person who plays the violin at Mỹ Lai in the film. From the time the war ended until today, he has lived alone, has had no family, received no salary, and has refused to acknowledge that anything American could possess any value…

He wasn’t guilty of any misdeed and was not connected in any way with the massacre at Mỹ Lai. Therefore there was noo need for him to seek “absolution,” or “engage in repentance,” as some have imagined. It was simply that Mike did what he did each year in order to satisfy his own feelings and to soothe the pain with which war had heaped the destiny of mankind in the past…

From despising the war, Mike went “whole hog” and came to despise, and hold himself aloof from, all of America—from the president to the congress, and to the flag. People willing to carry their ideas to an ultimate extreme like this are usually to be seen only in countries like the United States.

A film that remained faithful to the stories and the destinies of people so rich in human culture would surely have gone further and been better…We were all very aware of this, but our supplies, of film, money, and time did not allow this, and an even more decisive factor was the pressure of the Cinema Department and the “film censorship system.” They didn’t wish to accept this film. If I had gotten worked up about it, I’m sure that all my colleagues in the film crew would have supported me, but I was leery of the trouble that might ensue, and the possibility that the chiefs of the film studio who had so wholeheartedly believed in my and supported me might be mixed up in the trouble.

Order In Whose Eyes from the University of Massachusetts Press, or from Amazon.

All text and images are © 2023, Trần Văn Thủy, all rights reserved. Written permission is required for any use.