Chapter Twenty-Five

In the course of my professional life, I have many times had occasion to make films with TV stations and with colleagues in other countries. And each time there have been aspects both good and bad, both easy and difficult, in these collaborations.

The first time I made a film under these circumstances was with Channel 4 in England. As I recall, the formalities were very hard to deal with on that occasion.

When I was in London, I discussed the matter with Channel 4 and after that returned to Vietnam. Channel 4 then relied on Nel Gibson, an English director who was going to Hanoi, to deliver a letter to me so as to maintain contact. Unfortunately, Mr. Gibson died suddenly in his hotel, and the letter was retained by the police. I naturally never got to see it.

Channel 4 (actually Rod Stoneman), in a final strategic move, sent a letter directly to the Prime Minister Võ Văn Kiết suggesting that they rely him to have the letter conveyed to me.

On January 27, 1992, I was received at the Cinema Association. There Mr. Đặng Thế Truyền, a cadre in the office of Võ Văn Kiệt delivered the letter from Channel 4 directly to me with the request that I sign for it, and also let me know that the prime minister had said, “The director can do this or not as he likes, but don’t let them think that the government is prohibiting him from doing it.”

This episode showed me how clever the English are. Who in this life would ever ask a prime minister to deliver a letter to an insignificant little pawn like me? But that was the shortest, surest, clearest way to arrive at the desired goal.

A close friend of mine joked with me: “If it weren’t for Mr. Sáu Dân (Võ Văn Kiệt), Trịnh Công Sơn and many other southern artists and intellectuals would still be digging trenches in the rain.”

From the time that the assent of the prime minister was obtained, the formalities were all easy to carry out, and my work on films with other countries went smoothly.

The Department of Cinema, and especially anh Nguyễn Văn Tinh, who was in charge of dealings with other countries, gave me swift and eager assistance in carrying out this project.

The film was called A Spiritual World (Một Cõi Tâm Linh) and gathered together many stories concerning worship, yin-yang, filial piety and tombs from the North to the South, and concluded in a very somber manner with the music of Trịnh Công Sơn: “A Road Stretching for a Myriad Miles,” and “Intoning a Sutra for Mother.”

I had loved Trịnh Công Sơn from the time of my days and months lying in trenches in the jungle. When the Saigon Broadcasting station was opened, I would press a receiver to my ear and hear, faintly transmitted, “The cannon echoes every night in the city, the street sweeper halts her broom to listen,” and I would get goose-bumps. How could he be so stricken with sorrow? How could he love so intensely? A new world opened within me. Trịnh Công Sơn, Saigon, and the life of humankind, held sway over my thoughts from that time on. My dream was to get to see Sơn, to meet Sơn, to hear Sơn speak. This dream of mine was satisfied when I made A Spiritual World with the collaboration of Trịnh Công Sơn, Trịnh Vĩnh Thúy, and a film crew with their equipment. As we worked, Sơn wrote out for me the melodies of “A Road Stretching for a Myriad Miles,” and “Intoning a Sutra For Mother.”

At the conclusion of the film, I wrote the following words:

“When he was still a youth, this musician wrote,

‘What speck of dust took on my identity,

So that I could later on return to dust.’”

Trịnh Công Sơn himself acknowledged that “I am just a singer wandering over this earth to give voice to intuitions of mine that arise from empty dreams.

Now after several more decades, his music has gone into the hearts of millions of people. But he himself acknowledged that “I am just a singer wandering over this earth to give voice to intuitions of mine that arise from empty dreams.” Throughout his life, he pursued and worshipped the life of the spirit. Could it be that it is due to this world that he turned into Trịnh Công Sơn?

Only recently have I awoken to the fact that an awareness of the life of the spirit is a path, a religion, an important cultural legacy bequeathed to us by our ancestors. Could this in itself be a religion in the full and plain sense of that term—a religion that people worship in a completely willing and unshakable fashion?

I must say that the essential spiritual core of the A Spiritual Realm lies in the episodes that were shot in Huế: the graves, the ageless cemeteries, the mysterious legends associated with Mt. Ngự Bình, the little altars set out for the worship of Heaven on the boats of the Hương (Perfume) River, the various traditional practices that led the people of former days into eternal regions, and the river calls addressed to departed spirits—all these things are part of our non-material heritage, along with tales of filial devotion to departed parents, like the tale of the lass Bích Đàn… Ancient traditions such as these exist also in the North, but have been obscured and have failed to be transmitted to later generations. One can say that Huế, more than any other region in the country, is the place where values related to the spiritual realm and to the eternal realm are faithfully preserved.

I have many valued friends in Huế, among whom are the writer Tô Nhuận Vỹ and the members of his family. He is a very deep person and a person steeped in the atmosphere of Huế. With his profound understanding of Huế’s culture, he went out of his way to assist me in all the episodes of A Spiritual Realm that were shot in Huế. I still remember this, and am very grateful to him.

One can say that Huế, more than any other region in the country, is the place where values related to the spiritual realm and to the eternal realm are faithfully preserved.

In connection with A Spiritual Realm, with its many episodes full of incense smoke and burial grounds, I wish to add a few words, concerning the habits of film directors, as follows:

In the days when the director Lê Mạnh Thích was still alive, we often got together and traded stories about our profession. Once some younger film-makers made the discovery that in all the films of their elder Thích, there would always be a scene shot in the rain… and in all the films of director A there would always be a scene with a setting or rising sun, while in the films of director B, there would always be a scene of floating clouds. Then the younger folk made the discovery that in all of my films there would always be a scene with incense smoke and burial sites.

I was startled!

But it was a fact; in all the twenty-odd films that I had made, whether good or bad, there were, oddly enough, scenes with incense smoke and burial sites. Yes, in every single one of them, too many to give the details, such scenes occurred, and this was all as if by pure coincidence.

In stories concerning life within the country, the incense smoke and burial sites would be associated with war victims, martyrs, people from general walks of life, friends, and distinguished people of former times.

As for films dealing with foreign lands, scenes would appear, depending on the stories dealt with, of the graves of Frederik Chopin, Honoré de Balzac, Alain Cadex, (a genius of the type of Madame chúa kho), Victor Noire (a Parisian youth who was shot to death by the nephew of Napoleon III), La Fontaine, and Molière… in the Père Lachaise cemetery, there was the grave of Victor Hugo, and Alexander Dumas, and in the Pantheon various other famous Frenchmen. And then there the cemeteries in Marseilles, Montpellier, Germany, and Italy. And when we went to England we took the greatest care in filming the grave of Karl Marx in the cemetery at High Gate.

“The Eternal Gardens” in Westminster, a place where many Vietnamese literary and artistic people are buried.

No matter what country or city I came to, I would always seek out a cemetery. When I was in the US I paid repeated visits to the grave of Abraham Lincoln and to cemeteries of Boston, where I resided. When I went to Westminster, California, there was a cemetery called “The Eternal Gardens” in front of Green Lantern Village, the apartment complex where Hoàng Khởi Phong lived. This was a place where many Vietnamese literary and artistic people were buried. I made my way there, and spent a great part of one day seeking out and murmuring the names of many people of reputation, such as the writer Mai Thảo, the poet Nguyên Sa, the musician Phạm Đình Chương, the singer Ngọc Lan, the journalist Lê Đình Điểu, the playwright Vũ Hạ, the musician Trầm Tử Thiêng, the singer Thái Hằng, and many others besides.

Right after making A Spiritual Realm I worked with the NHK station in Japan to make the film There Is a Village, which concerned Phù Lãng Village in Quế Võ district, Bắc Ninh Province, where people had been engaged in tilling the soil from very ancient times. It was a very poor village, but the people there behaved with great decency and generosity to each other; grandfathers and grandmothers, fathers and mothers, sons and grandsons, and all the neighbors loved and took care of each other, with never the slightest sign of a dispute or conflict.

I was very puzzled as to why the Japanese were willing to spend a lot of money to have me make a film concerning one of our poor Vietnamese villages, and were even willing to lend me a helicopter to assist in the filming…

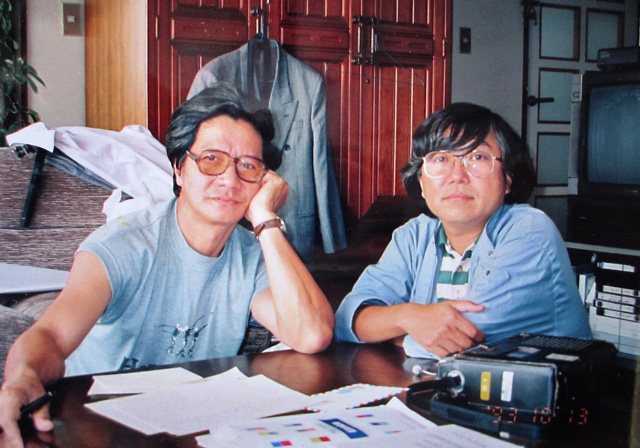

With Tako Norio in Tokyo, discussing the budget for the film There is a Village.

In Tokyo, when my Japanese friends viewed the film with me, they said, “This is an ancient tale of the present day!” Only then did I understand that the Japanese themselves had experienced the kind of poverty portrayed in the film, and had behaved with the same decency and kindness to each other. But now, having become more prosperous, and having attained a higher status, their feelings for each other were no longer like what they had been in the past. And they knew better than anyone else that sometimes an improvement in prosperity can cause a deterioration in human feeling.

They wanted their own children and grandchildren to gain an understanding of this.

This important experience is now being tasted in Vietnam, but it seems that we are not fully awake to it.

Visiting and discussing filmmaking with the film directors of the ABC broadcasting station in Australia.

After that I was invited to help make such films as The Vietnam Peace with directors working for the ABC broadcasting station in Australia, and Nam Retour sur Image (“Return to ‘Nam’ in Images”) with Quack Productions in France (this dealt with the return to Vietnam of Tim Page, an English photographer with an international reputation).

Aside from the above, there were also many other invitations, such as one from the French Film Directors Association (Société des Réalisateurs de Films) of the French Film Association (La Cinémathèque Française), another from the Danielle Mitterand Foundation (Fondation Danielle Mitterand)… and especially a handwritten invitation from the famous historian and journalist Jean Lacoutoure.

On one occasion after the banning of Hanoi in Whose Eyes, the film was shown on the sly to general Võ Nguyên Giáp and his family at the documentary film studio. After the showing, just as people were sitting and drinking tea, the electricity was cut off, and the sky was more or less black outside. The general stood with me for a long time, and finally said, “I imagine you’ve lost a lot of sleep over this?” Then he extended an arm around me, patted my back, and said, “Life is the mother of Truth…”

This is a saying very easy to understand and very easy to trot out in a glib fashion among shallow people with no particular commitment to anything. Only people who have passed through many experiences on the road of life are able to understand it deeply; and the more they experience, the deeper will be their understanding. In this case the experience of the old general himself after having passed through years of warfare lay within that saying.

Later on, I had the good fortune to have occasion to visit the general’s family many times. Sometimes I went in order to shoot a scene, and sometimes I went with friends from other countries who were visiting the general. I had a close friend who was a Frenchman, older than me by five months, with whom I was a sworn brother. His name was Orso Delage. He was a member of Lumières d’Asie, a charitable organization. He was very dedicated to charitable work in Vietnam and had done a lot of useful work with me to help little children and poor people…

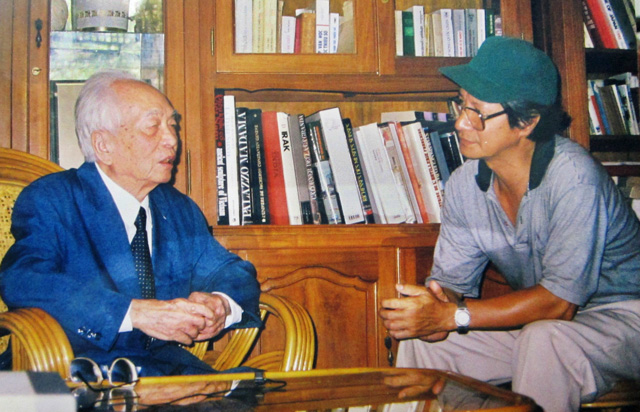

I had the good fortune to have occasion to visit the general’s family many times.

He had long harbored a wish to meet General Võ Nguyên Giáp, a person whom he deeply revered. In his house in France, he had a corner reserved for souvenirs of Vietnam, and especially Điện Biên Phủ. When he came to Vietnam to work with me, he said, “Arrange for me to meet General Giáp, and I’ll do anything you wish!”

I took Orso and his friends to see the general and his family on three different occasions.

They met in a very cordial manner, like friends who had known each other for a long time. Orso was totally satisfied. Later on he suggested the idea to me of building a kindergarten and a center for the young in Mường Phăng, a place where the general had had his headquarters during the Điện Biên Phủ campaign, or perhaps in Lệ Thủy in Quang Bình Province, the homeland of the general.

I remember that on the many occasions when I visited him, the general would always say to me when seeing me off at the door: “You have to keep an eye on the little ones, you know! Don’t grow lax with them. If they start misbehaving, you’ll be miserable!”

As for my “professional affairs,” there would surely be a gap in the account if I didn’t say a few words about Mr. Trần Độ. He was the head of Cultural Affairs, an administrator of talent and dedication who maintained close relations with artists and intellectuals. I think that if I should now ask the people who had dealings with him, they would all surely agree with this assessment.

He took intense delight in any sort of new thinking, and he loved the articles that appeared in the pages of Văn Nghệ during the period when Nguyễn Ngọc was general editor there. He loved Trương Ba’s Soul in the Butcher’s Skin1 and Hanoi in the Eyes of Whom.

In Trần Độ’s Memoirs, we can read such passages as the following:

“I have a special love and respect for writers, artists, and performers, because their labors are of a special type, and I always feel that they are a precious resource of the people and that the talented ones in particular are a source of national pride…

We can have a great many department chiefs and deputy department chiefs; and can have a great many prime ministers and deputy prime ministers, but we can only have on Xuân Diệu, one Nguyễn Tuân, one Chế Lan Viên, one Văn Cao, and Trần Văn Cẩn, one Nguyễn Sáng, and one Bùi Xuăn Phái… None of the foregoing people could be exchanged for anyone else. Due to these considerations, I usually regard artists with a high degree of tolerance and a deep respect for their professions. I don’t subject their productions or their lives to narrow demands, and I am ready and willing to create conditions for them that will enable them to exercise their abilities, so as to serve the people and serve the nation.

“A culture that is not free is a culture that is dead. A culture that consists entirely of traditional practices is also a culture that is dead. The more the authority of the leadership is increased, the more culture will be strangled, while cultural values and fine artists will grow ever rarer.”

As far as I myself am concerned, I regard him as a benefactor, and a person of feeling and principle. He rescued Hanoi in the Eyes of Whom and opened the way for The Story of Kindness, so that people could watch it.

As I have related above, Mr. Nguyễn Văn Linh told me to make a “Part 2” when he saw Hanoi in Whose Eyes—and that was The Story of Kindness. Naturally it was necessary to invite all the gentlemen in the Cultural Affairs branch to see the film first. Mr. Trần Độ took the people in his department to view it. It was shown in the afternoon in the documentary film studio. After the film was shown, everyone went upstairs to drink tea and exchange opinions. Everyone looked apprehensive—the atmosphere was in fact completely devoid of ease and gaiety. Mr. Trần Độ kept looking as if he was hesitating about something.

So I asked,

“Anh Đô! How do you feel about it, now that you’ve seen it?”

After a moment’s hesitation, he said,

“After seeing it, I feel quite at a loss as to what to say. You gentlemen give us your opinions first.”

Perhaps someone will be disinclined to believe that he used the expression “quite at a loss.” But that is the absolute truth.

It was a simple reaction, just as the reaction of Mr. Nguyễn Văn Linh had been after viewing Hanoi in Whose Eyes: “If that’s all it amounts to, then why was it prohibited? Or maybe I failed to understand it because I’m a man of limited education?”

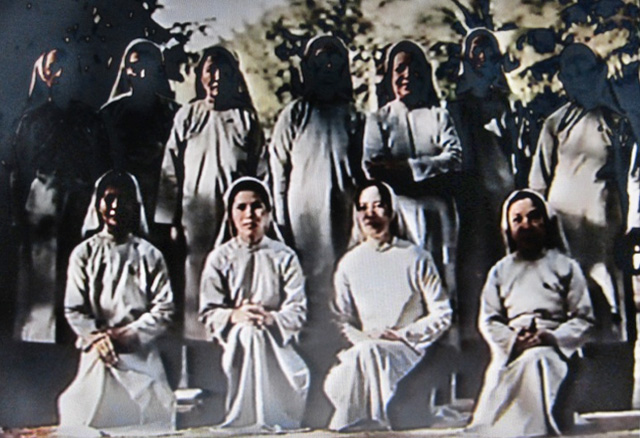

I told them in detail about the dedication of those nuns and the privations they endured so that they could care for the lepers in the Quý Hoa leprosarium.

Some other people cautiously expressed a few opinions. Then he turned to me and asked,

“How about the sections portraying the Catholic sisters?”

I told them in detail about the dedication of those nuns and the privations they endured so that they could care for the lepers in the Quý Hoa leprosorium—things that I had witnessed with my own eyes. He listened attentively and then, slowly and with emphasis said,

“If that’s the way it is, then it must told the way it is—what else?”

In The Story of Kindness, there are many ideas and episodes that had their origin in the views expressed by Trần Độ to artists and intellectuals: With regard to the use of the word “people,” for example, he had said,

“It’s a truly strange thing, comrades, there isn’t a place in the world where the word “people” is used as much as it is in our own country, we have such phrases as “people’s artist,” “people’s journalist,” “people’s army,” “people’s court,” and “people’s committee,” but the people have no power whatsoever. For example when we ourselves get a foothold in the central government, we immediately gain a sense of power, a sense of freedom, and a feeling that people respect us more than they did previously.”

But then he himself said, “When I’m in office, I feel that I understand everything; but now that I’ve withdrawn from office, I feel I don’t understand a thing. Now when I read Buddhist sutras, I feel that they’re splendid!

In March 1989, when I returned to Vietnam from France, I went to see Mr. Trần Độ to report what had happened and to chat, but because I had just arrived home, I didn’t dare mention that I had been invited to return to France a few months later.

Only when the day to set out again drew near did I mention the matter to him and ask him to make a decision authorizing me to leave. He said,

“Why didn’t you mention this at once the last time?”

“Why should I have mentioned it at once?”

“Because I’ve lost my position!”

Then, after thinking a few moments, he said, “But you must go! Let me call Nghiêm Hà here.”

Nghiêm Hà arrived. I don’t know what Trần Độ said to him, but the next day I received an authorization to go to France signed by Trần Độ—he was out of office to be sure, but the date on the authorization paper was a date when he still held his position. He truly believed in people.

That was Trần Độ!

The death of Trần Độ was felt very deeply in the army and in the world of the arts, because he was a person of such extreme insight. People’s feelings for him were entirely natural; there was nothing the slightest bit forced about it. He moreover fulfilled a need for those around him who wanted to have someone to turn to whom they could trust, who had fine human qualities that they could cling to.

…My wife and I brought a funeral wreath inscribed with the words: “In immense sorrow for anh [elder brother] Trần Độ”; and, on the line beneath: em [younger sibling] Trần Văn Thủy.”

Ladies selling funeral wreaths went ahead of us, bearing their wreaths. When we passed through the gates leading to the place where the observances were to be held, we were stopped by a couple of guards. One fellow was passing a radar machine over the wreaths so as to detect such things as explosives. Someone standing near him looked at the words on our wreath, and said in a rough voice:

“It has been publicly announced that people are not permitted to have “immense sorrow”—so why does your wreath have the words “immense sorrow?”

Only then did I grow dimly aware that there was such a directive; and later on I learned that this was indeed the case—even General Giáp was stopped because of his wreath.

The fellow with the “mine detector” said, “Look—above it says “elder brother Trần Độ,”; and below it says “younger sibling Trần Văn Thủy.” The regulations say that family members are allowed to use the words “immense sorrow.”

Before I had a chance to make any response, the two fellows waved us in. We were both old enough to be their parents.

So it turned out we were related to Mr. Trần Độ and didn’t know it! What an intriguing thing! Those youngsters weren’t aware that his real name at birth was Tạ Ngọc Phách—he had not even the remotest relationship with the Trần clan. I thought in my heart of hearts, “When he took the alias Trần Độ many years ago so as to be active in the revolution, did he foresee the current situation? Could anyone overhear him giggling in his coffin?”

And so we went in.

Inside the memorial reception hall the words “immense sorrow” that one customarily sees inscribed on the walls were covered over with black cloth, upon which large letters made from white paper had been hastily applied that said, “Memorial Ceremony for Mr. Trần Độ.”

As for what was done and said in the memorial ceremony itself, this has been much talked about and may be seen on the web, so I shall not repeat it here.

Allow me to add that I do not take the slightest delight or pride dragging such famous names as Phạm Văn Đồng, Võ Nguyên Giáp, Nguyễn Văn Linh, Võ Văn Kiệt, and Trần Độ into this humble and insignificant account of my adventures.

There is nothing earthshaking about it! There is nothing interesting about it!

I have no choice but to recount these matters because they are the truth.

I am grateful to these gentlemen because they were well-disposed to me and because they rescued me from difficulties. It would in fact not be saying too much that they protected me during the long years when Hanoi in Whose Eyes met with disaster, and when The Story of Kindness was surrounded with setbacks.

As for all the “secrets of the inner palace” and “great affairs of state” it is not for someone in a humble walk of life, however I interested I might be, to make any evaluations. Let history be the judge of such things.

But I am sad! Above all, I am sad!

I am sad because these were precisely the people with power, the people with the ability to do earthshaking things—so why is the country still afflicted with so many obstacles, and so many deficiencies in humanity? I am sad because intellectuals and artists, people of good will and ability, are still isolated, still indignant—and what is still more sad is that the more good will and the more ability they have, the more they are isolated and indignant!

Many times I have asked myself: “Why?”

It isn’t hard to explain why.

People who like to play with words say that these things are due to “systemic mistakes.” That is true enough! But perhaps if we truly take pity on this country and upon this people of ours, we must call things by their true names: because however we fix our attention of the accomplishment of each task, we still must urge each other on and hold each others hands as we walk beneath a road sign inscribed with the word “Labyrinth!”

| 1. | This was a spoken drama written in 1983 by Lưu Quang Vũ (1948–1988) based on a folktale in which Trương Ba, a cultivated man, dies in an accident, after which his soul enters the body of a pork vender. The tale had served as a subject for chèo theater throughout traditional times The play was performed in the Hanoi opera house under the direction of Nguyễn Đình Nghi, the son of the poet and dramatist Thế Lữ. It won the Vietnamese National Drama Award in 1990. In 2002, it was performed in London under the title “The Butcher’s Skin,” thus becoming the first Vietnamese spoken drama to receive international attention. Lưu Quang Vũ and his wife, the poet Xuân Quỳnh, were both killed in a traffic accident in 1988. |

Order In Whose Eyes from the University of Massachusetts Press, or from Amazon.

All text and images are © 2023, Trần Văn Thủy, all rights reserved. Written permission is required for any use.