Chapter Twenty-Seven

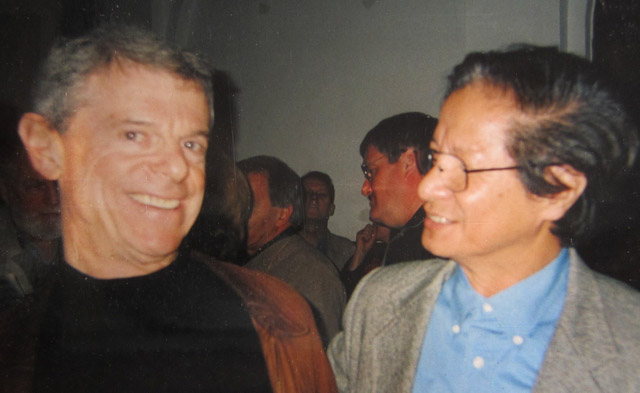

The American film director Peter Davis was also a personage worth remembering. He was famous as an anti-war activist, and was the director of the film Hearts and Minds, which won an Oscar in 1974. From the time of our first meeting Peter behaved in a very friendly manner to me, as if we had always known each other, because he was very concerned with “the Vietnam War.”

Peter Davis, famous for his film Hearts and Minds, which won an Oscar in 1974.

We were both invited to a film festival in Brooklyn that lasted from November first to 30th in 2002. Thirty-six films concerning Vietnam were shown at this event, including both documentary and narrative films, and many well-known directors were present, such as Oliver Stone, Michael Moore, Peter Davis, and Francis Ford Coppola. The poster advertising the Brooklyn festival introduced me in the following terms: “Trần Văn Thủy, a Vietnamese film-maker described as the Francis Ford Coppola of Vietnam.” Francis Ford Coppola is an American director famous throughout the world for such films as Platoon (1970), The Godfather (1972), Apocalypse Now (1979), and many other prizewinning works.

What do you think with regard to that?

The United States is a free country; people there evaluate and criticize things just as they please. Even though that sentence appeared on a poster to be displayed before the public, it was very likely written by some random individual in some random moment.

I am actually embarrassed and… ashamed at this maladroit and exaggerated comparison. I know who I am. And I know who Francis Ford Coppola is: a great, powerful, wealthy director. But I can nevertheless observe that if he had been born in Vietnam and had made films there, he wouldn’t necessarily have dared to do as I did. And as for Mrs. Marilyn Young, the dean of Graduate Studies at New York University, after she saw The Story of Kindness in the Brooklyn Film Festival, she, in a voice choked with emotion, before the entire audience, “Many of us Americans are prejudiced with regard to Vietnam—we imagine that it is a closed and controlled country without individual voices—but now that I have seen The Story of Kindness, I no longer think that way.” (I must say that this American was terribly gullible… she had no idea what troubles the director had to face in order to make the film…)

This woman sent me a letter inviting me to return to the US in the December of the following year to take part in a sociology conference. I attended that event as well. I still have the conference program. It was very cold on the east coast of the US that year.

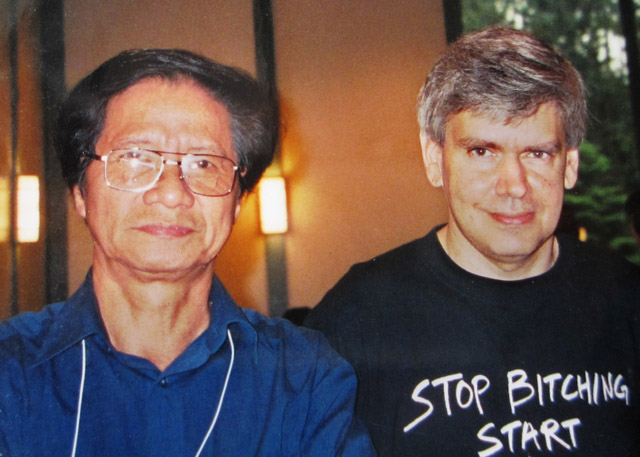

To return to the Brooklyn conference—it was there that I met John Gianvito, a well-known American filmmaker with a solid reputation as an organizer of international film events. After seeing five of my films at the Brooklyn conference, John invited me, under very generous terms, to return to the US in 2003. His invitation was couched in very informal language, as if he were joking: “Come pay me a visit, so we can enjoy each other’s company!”

In accordance with his invitation, I came to New York at the beginning of May 2003, in order to participate in “The 49th International Film Seminar—Robert Flaherty.”

About two hundred filmmakers from around the world participated in that conference. So that the event could have the atmosphere of a rural excursion or camping expedition, the planning board requisitioned the entire sprawling campus of Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York (north of NYC, on the Hudson River) after the students had left for the summer, with lawns, forests, and architecture reminiscent of a historical legend.

All of us who took part felt that there had never been such a conference anywhere, though I personally had had the good fortune to take part in dozens of other conferences in Germany, France, Russia, Japan, Australia, and so on… Many films made a strong impression on me; and there were many filmmakers of ability there, with many highly original ways of working. Everyone paid close attention to the films and participated eagerly in the discussions. I had the feeling that this was an international training session for documentary filmmakers.

John was in charge of many of the discussions; he posed many questions for me to respond to with regard to documentary films in Vietnam, and about the processes I had used to make the films of mine that were shown at the symposium. At the close of the event, the title “Witness to the World” was bestowed on the Japanese director Tosho Moto and me.

Tosho Moto was seventy-five years old that year, and five of his films were shown at the symposium. He had been accompanied to New York by his wife and a film crew. Most regrettably, he passed away three years after returning to Japan.

John Gianvito was especially interested in The Story of Kindness. There is nothing strange in this, because in many American universities a number of my films, including The Story of Kindness, were on the curriculum of various courses, and had been shown repeatedly to several generations of students. I was very astonished when, five years after the Robert Flaherty Symposium, John brought The Story of Kindness to be shown at the Viennale Festival in Austria.

Below is a passage from a letter sent to me by John Gianvito, in which he speaks of the films being shown at the Viennale:

…I have spent as much of my adult creative life as a film creator as I have as a filmmaker. It was suggested that I could program one or two events at this year’s festival of the works of others… Bringing your film, The Story of Kindness into the selection was for me a simple and powerful method of restoring the dignity and full dimensionality of the Vietnamese people after bearing witness to the previous films with their brutal words and deeds.

Both in front of your camera and behind it, The Story of Kindness enables us to encounter hearts who have somehow managed in the face of the most unimaginable atrocities, to maintain a place for compassion for all. The ‘truths’ that your film explores are not easy ones and among its strengths is its capacity for self criticism and criticism of the state in some aspects. Without this broad and honest critique, The Story of Kindness might have been lost to the dustbin of history, one more propagandistic diatribe. Nor is it a naïve film. While anger is not explicitly manifest there can be little doubt about why so many of your friends and colleagues, artists and film-makers, were dying early of cancer-related illness. Both Agent Orange and all those responsible for its use…

I have many thoughts, as I think you know, about the topic of what is a political film, and what forms of socially engaged cinema are the most effective. Among them is my clear opinion that any film that reawakens us to our humanity is in essence a political film. Because every day we are bombarded with experiences that result in nullifying our senses, in shutting us down not only to the profound misery that unfolds every second or every day in much of this planet, but in shutting us down to our own awareness of self and soul. Thus, many years later, The Story of Kindness continues to revivify, and I can report that a number of people who attended the screening in Vienna had this feeling…”

John Gianvito: The Story of Kindness enables us to encounter hearts who have somehow managed in the face of the most unimaginable atrocities, to maintain a place for compassion for all.

First of all, I must let you know that the tickets to this film sold very fast and that the seats (about three to four hundred) in the large theater were totally filled. I was delighted also to see that, purely by chance, the filmmaker Joseph Strick (director of the Oscar-winning Interviews With Mỹ Lai Veterans) was present at the festival and mounted the podium with me prior to the showing of The Story of Kindness. Afterwards he told me that this film moved him very much, and he thanks you for having given him an opportunity to see a part of the lives and struggles of the Vietnamese people in the years following the war. A highly regarded German film collector named Olaf Moller was also deeply impressed by your film and wrote me a letter in which (aside from some words of praise for one of my own films), he said that The Story of Kindness was a great surprise to many people, a view that was also expressed to me by many other film-makers. Finally, I have received a splendid letter from a person I am not acquainted with who wants me to convey to you his strong feelings with regard to your film…

John Gianvito had requested the spectators to give him their reactions to The Story of Kindness. Below are the comments of a freelance critic:

Dear John Gianvito:

This is a somewhat belated reaction to your invitation for a feedback concerning Trần Văn Thủy’s The Story of Kindness. I had to leave quickly after the Vietnam screening, so I couldn’t approach you directly. But I still want to tell Trần Văn Thủy the film-maker that it was among my most stunning viewing experiences at this Viennale: For the first minutes of the video’s screening, I had no idea where this was supposed to be going. But while the essayistic flow of thoughts never seems to settle for one definite destination until the very end, what I gradually came to understand, see, and feel in the following half hour was a startlingly purposeful and powerful exploration of a scarred country.

In its exploration of the ruptures in Vietnamese society, this must be one of the most devastatingly gentle films I have ever seen, and this without making the kindness and gentleness expressed register just a sarcastic ploy.

I hope these rather awkward notes are of any interest to you.

Greetings,

Joachim Schultz

(freelance critic for the Viennese city mag “Falter”)

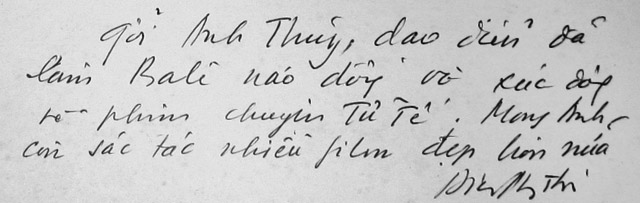

I beg to state here that I have never dared to regard The Story of Kindness as a good film; I have thought of it only as a beneficial film. Fortunately it aroused great interest everywhere. Mrs. Điềm Phùng Thị, a great name among the world’s sculptors, whose name is recorded in the Larousse Dictionary, saw the film in Paris and sent me a few words written on a poster: To anh Thủy, the director who excited and moved all of Paris with his film The Story of Kindness…

I am fully aware that love, hate, praise, and blame are the most ordinary of affairs; therefore I don’t feel happy when praised, nor sad when blamed; I only do what my heart urges me to do. And in fact there are quite a few people who don’t care for my films. I have a story, a little piece of memorabilia, concerning praise and blame—I have been perplexed about whether I should recount it or not…

The note written to Thủy by Điềm Phùng Thị.

…In my film studio, when the time for end-of-the-year assessments came around, many of my colleagues gave a high score to The Story of Kindness, but the director and “people’s artist” Ngọc Quỳnh gave it a “zero,” even though the stipulation was that the lowest score to be given for a film produced by the studio was “five” (the highest was “ten”). He felt that the film failed to adhere to the path determined by the party. I must say that he was a most conscientious person, who lived for the Party and paid the party’s dues with absolute regularity. When there was no money left in his house, he forced chị Nguyệt, his wife, to produce enough money for him to pay the dues.

At the end of his life, when he was too weak to walk, he requested his party branch to gather by his sickbed. He was a model person in every respect, and believed in the party to the last moments of his life. People like him are very rare nowadays.

Because of this, when commemorative ceremonies are performed in my film studio’s “office of traditions,” he is still honored as a bright example, and sits “at the head of the offerings” next to the director and people’s artist Bùi Đinh Hạc.

When he passed away, I was the only close friend present when his clothes were changed to prepare him for burial. He was a model of goodness in his era.

Order In Whose Eyes from the University of Massachusetts Press, or from Amazon.

All text and images are © 2023, Trần Văn Thủy, all rights reserved. Written permission is required for any use.