Chapter Twenty-Eight

On Writing and Writers

I don’t know why, but I have always particularly loved and admired army writers. I knew anh Nguyên Ngọc when we both were stationed in Zone 5 of the southern war front—but no, it would be more correct to say that I got to know him when I read “The Xà Nu Forest” when I was still sitting on a bench at school. In the period when he was the editor in chief of the journal that became Văn Nghệ (“the Arts”), he injected new life into the world of letters in a manner rarely seen. He was the student, or more properly the disciple, of Phan Chu Trinh. He was vitally concerned with proposals for the betterment of society.

Nguyên Ngọc saw nearly all my films, and he always gave me encouragement. The book And If You Go To the Ends of All the Seas, which went through two editions in the US, was the result of his encouragement, as I have recounted above.

That Nguyên Ngọc concerned himself with my writing in this way is certainly a great honor for me. I beg to confess here that I never wrote anything with a view to collecting royalties. I have written little, and most of my writing has been in the form of play scripts, film scripts, and a number of articles. My teacher, Mr. Roman Karmen was a person of uncommon literary gifts, perhaps because his father was a writer and wished for his son to follow in his footsteps, and so gave him the name Roman (which in Russian means “novel”). Roman Karmen wrote scripts for all the films he shot, even into old age. He was both a director and a writer of film scripts. He also had a voice that was ideal for reading film scripts. Such a teacher, who provided me with such a splendid example, was a great encouragement to me. In Vietnam I have observed that many people who make documentary films have to rely on others to create their films scripts. This is an entirely ordinary situation but it nevertheless seems a little strange to me—strange because it seems to me that no one else could have as deep a grasp of the film’s soul as its maker (except in those cases where the film consists of empty platitudes and there is no “soul” to be grasped). One must write. For this reason documentary films are sometimes called “author films.” But if you can’t write, and others write better than you, then there’s no help for it.

As for the scripts for The People of My Homeland, The Place Where We Once Lived, Betrayal, Hanoi in Whose Eyes, The Story of Kindness, There Was a Village, A Spiritual Realm, Blind Wise Men Examining an Elephant, and A Barbarian of Modern Times, I wrote them fairly easily with the impetus of personal inspiration and the contributions of friends. My habit in making films is to write whatever I think and to put everything I shoot out on the table, so that my colleagues can suggest additions or abridgements.

That Hanoi in Whose Eyes and The Story of Kindness attracted the attention of many viewers was large measure due to their films scripts. Of course the modern documentary films that are now being made don’t use so many words, but I have the ill fortune to belong to the “wordy” generation—whose way of proceeding is now quite out of fashion. I’m grateful that Nguyên Ngọc has praised my films scripts, but I would advise young directors not to tread the same path that we have. The fewer words, and the less music, the truer the film. No film has ever been praised if it wasn’t true.

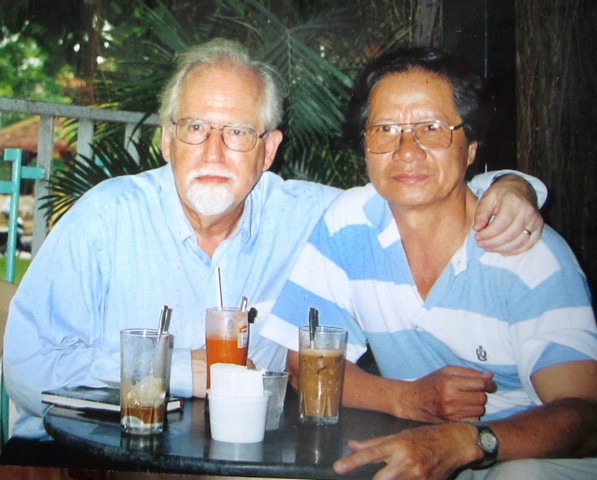

In connection with the topic of the role of words in documentary films, I beg leave to add here that, a few years previously, anh Eric Henry, a director of Vietnamese and Chinese courses at the University of North Carolina, sent me a draft of a book that he and a Vietnamese person, anh Vũ Hân, had put together to teach Vietnamese in the US, Eric Henry was a former American soldier who had been trained in Vietnamese in an army school in Texas, starting in 1969. In 1970, he came to Vietnam as a translator, and later studied Chinese as well.

Eric Henry, director of Vietnamese and Chinese courses at the University of North Carolina.

In this body of material, Henry and his associate Vũ Hân had copied out all the words in the film script of The Story of Kindness, but most significantly of all, they introduced all the words and expressions in the film, in the order of their appearance, that they felt were valuable, laden with content, of variable meaning, or metaphorical, and provided examples of the use of these expressions in sentences. They also created questions regarding each scene so as to serve as a basis for discussion among the students. A number of newspapers in foreign countries had also printed the entire film script of The Story of Kindness. I never imagined that the script of a documentary film could become the object of such general attention. Every expression in it has been analyzed and examined from every angle. It has been translated into German, English, French, and Japanese. The translators were all linguists with a profound understanding of Vietnamese, who were able to feel the soul of the language; this is most apparent in the French and English translations.

It is my habit to feel apprehensive when people overpraise me. But this feeling turns into a sensation of indebtedness when people believe in me and value me.

The writer Lê Lựu used to live near me when my house was on Lý Nam Đế Street near Phan Đình Phùng and Hàng Bún. More than almost anyone else, he was endowed with the charm of the countryside. To be able to write A Lost and Distant Time (Thời Xa Vắng) in a period when literature was so hemmed in with restrictions, he must have been a person of great dedication and ability. I learned many things from him, such as his way of applying words to situations, and the literary use of language, which I used in writing play and film scripts, as well as other things.

As for Nguyễn Khải, I have a great admiration for his literary power. It seems that in the flavor of his writing one can sense the soul of a priest or philosopher, especially in the impassioned essays he produced at the end of his life, such as Thought of Too Late, and In Search of What I Have Lost. Once when I was talking with him I made this confession: “I stole a passage from you in The Story of Kindness. Near the end of the film, where you see people in ragged clothing jostling each other in the dust of the streets, just before the long episode dealing with the fine mathematics teacher who has to sell vegetables to support himself, I put in the exact words of a passage written by the “priest” Nguyễn Khải: “Man is a creature who refuses to live with his arms crossed. He always strains toward the superlative, the infinite, the eternal—that to which human beings can never attain.”

I got to know and value Nguyễn Minh Châu in my days of poverty and obscurity. We met in a dilapidated house that served as a military dormitory on Ông Ích Khiêm Street. He was a gentle, deep man, a person who reacted with feeling to everything in life, a person who regarded every spot of sunlight, every drop of rain, and all the eddying crosscurrents of life, with tenderness. He was a person who felt passionately about life right up to his last moments. Read his “Someone’s Consolation”; read the words, the drafts, that he left behind. Chị Doanh, his fine and gentle wife, gathered them together for me to read. After reading them, I loved him all the more. During the last days of his life, he was undergoing treatment at the Pháp Hoa Temple in Đồng Nai. I went to visit him, and later found to my astonishment that he had written about my visit in a letter he sent to a friend, anh Nguyễn Trung Thu in the Culture and Arts Bureau.

(In Words Left Behind, p. 472, Hanoi Publishing House, 2009, Nguyễn Minh Châu writes: The other afternoon Thủy (Hanoi In Whose Eyes) came to visit me—he had brought along a Colonel (the principle of the Lục Quân School no. 2) who lives eight kilometers from me with the following purpose: This gentlemen reads your work a great deal and loves you—if you need anything you can rely on him,” Thủy said. When I bade them farewell before they mounted two separate vehicles, I noticed that this gentleman clasped his hands and made obeisance to Thủy as if he were a saint. ‘You are so daring, so courageous; I greatly respect you.’ And the three of us each went his separate way.)

(LTD:) Thủy said,

“Perhaps someone reading these lines will think that it’s off the subject, or illogical, to drag four writers in the military into the discussion.

I [Lê Thanh Dũng] said to Thủy,

“That’s not the case. We didn’t just crawl into the world from under the branches of a banana tree—we must surely remember the teachers we have had in this life. Our elders had a saying, ‘Studying ten thousand things with a teacher doesn’t come up to studying an inch with a friend.’ Having people who are both teachers and friends is a very fortunate circumstance; one need only fear that we will listen but not understand, that we will look but not perceive.”

I have had many teachers of this kind. If Heaven gives me strength, I shall write about these teachers. These four writers in the army were my teachers and my friends. I learned a great deal from them. If I don’t study, how can I continue practicing my profession? If my teacher, Mr. Roman Karmen could come to life again, he would surely be unable to comprehend what this land of ours needs more than writers rich with human integrity and rich with intellect.

With the writer Nguyên Ngọc at a Vietnamese-American literature conference.

One thing that makes me a little worried, and a little regretful, is that it seems (seems only) that these four gentlemen by rights should have been more marvelous, more prolific, and more famous, if they had not been required to wear iron hats for dozens of years—nay, for nearly their entire lives. If they had not been forced to endure the deadly restrictions imposed by those hats, those four men would have lacked for nothing if compared with those four stars of the Vietnamese literary world in the first half of the twentieth century: Nguyễn Công Hoan, Vũ Trọng Phụng, Nam Cao, and Ngô Tất Tố, four writers, four HUMAN BEINGS, who devoted the whole of their painful existences to the perversities and hidden areas of this life of ours.

Order In Whose Eyes from the University of Massachusetts Press, or from Amazon.

All text and images are © 2023, Trần Văn Thủy, all rights reserved. Written permission is required for any use.