Chapter Twenty-Nine

I have loved the language of my land

From the time I first saw light,

Oh people…

My gentle mother with her distant lullabies…

A couple of months ago I referred to these lines when I was sharing some impressions of mine concerning Phạm Duy in a documentary film directed by Đình Anh Hùng and produced by Phương Nam Company.

From the middle of the last century, these words entered into the souls of who knows how many generations of Vietnamese, and they remained in me like traveling bags for the journey of my life, especially when I was growing up, and when I was making films, or choosing topics, or facing hardships.

I don’t know how the director Đình Anh Hùng made use of those scenes, or what he chose to cut, but I shared my deepest feelings with him on the subject of patriotism, a subject as old as the earth, but also so new that nothing could be newer. I said that loving one’s country was a part of human nature, and especially of the nature of Vietnamese.

I also spoke my mind about a further point: in this country you would have to light a torch and conduct a painstaking search to find a few people who don’t love their nation (not counting corrupt officials and a few insane people). But one must note that each person expresses his love of country in his own way. And in my opinion, no one has an exclusive right to love his country; and no one has an exclusive right to publicize their own love of country or to dictate to others how they should love their country.

We may be unequal in rank, status, money, and power, but Heaven and our ancestors have bestowed on us an equal right to love our ancestors. This is a point as old as the hills, and I have spoken of it many times in interviews.

Read this excerpt from a letter written by the scholar Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh to Nguyễn Thúc Kháng in 1924:

There is an enormous gulf between a genuine Confucian scholar like yourself, and a person like me, who no longer believes in the thought and methods of the past, a barbarian of modern times, the product of a miscellaneous and gap-ridden education, who is trying to find a few truths in that same past, but who naturally knows no more than Mr. Kháng. And in any case that past still rises before me like a never-before recognized source of life and light.

We met each other on the road, and everyone thinks we are going in the right direction, precisely because the road we travel doesn’t yet exist. It is as if, in the end, we are both seeking truth, and though we don’t agree, we still have to move in the same direction.

(Material drawn from “The Birth of the National Script and The Barbarian of Modern Times” by the American Historian Christophe E. Goscha)

Terrific, don’t you think? These people of olden times can make us burn with admiration!

In the course of pursuing my profession, I have become involved in many long, complex situations related to “love of country”; if I wrote them all out, people wouldn’t like it, because they would feel that I was laying down a model or doctrine for people to follow. They would cut those passages out for fear of violating a taboo.

Another fact of life is that with us Vietnamese, when you mention the words “love of country,” the words sometimes seem to denote something simple, but also at times something of high status—and so great is this implied status that few people dare to utter in public the words “I am a person who loves his country!”

Loving one’s country has turned into a mark of social rank!

We Vietnamese are truly peculiar!

So let me now risk stating the following: “I am a person who loves his country!”

All the films that I have made, all the things that I have written, all the lonely roads that have walked on, all the desperate situations that I have endured have arisen due to my… love of country! Don’t waste your time looking for some powerful faction controlling me from behind—I am neither clever enough, nor stupid enough, to be involved in any such thing.

When people see that anyone differs from themselves, thinks differently from themselves, or wish for things other than what they themselves wish, then they keep on declaring that such people are enemies. How have you behaved in life, what favors and injustices have you dispensed, that you should have so many enemies?

There is nothing good about a person having so many enemies! Don’t you agree?

For many years on end, security personnel stood guard around my home, and on many occasions would arrest and interrogate me merely because they suspected that behind my back some political force was directing my activities (I kept a full record of who did the interrogating, how many times, and on what dates, in what locations, how many nights passed, and what the content of the interrogations was).

They looked into all my associations with people, and examined all the names and phone numbers in my notebooks so as to interrogate me more carefully. They asked me about all my relationships with Vietnamese intellectuals inside and outside the country, and even went over every particular of my relations with Mr. Trần Độ—when their questioning reached this extreme, I thought it was fantastically odd. They also questioned me about the invitation to engage in discussions at the French Foreign Affairs Department extended to me by Mr. Blanche Maison before he came to Vietnam as an ambassador. They asked me why there was an organization called “Friends of Trần Văn Thủy” in Paris. These were of course all silly questions, but I gave clear and polite responses to all of them. I felt that the way they spoke to me also expressed a degree of politeness and respect. Nevertheless, a fellow named Bảy once couldn’t suppress his rage when interrogating me and, pointing his finger in my face, said:

“You’re a reactionary! You’re in communication with forces that want to destroy us! You are conveying materials to other countries, and taking materials from other countries into Vietnam!

I pulled the apart the lapels of my shirt so as to expose my chest, and, no longer able to speak calmly, said, “Shoot me! If you have such clear knowledge of all this, just shoot me! What’s the point of going on with these questions!”

Though a public security officer, he didn’t understand a fundamental principle of the law: that a person can be convicted of a crime only as the outcome of a formal court trial.

The above event took place on April 20, 1991 in a place that I later learned had once been the headquarters of the Saigon police. Just as working hours drew to a close, a vehicle parked by the front gate. They told me to get into the car. In the car, aside from the driver, there was a very young security guard, about my son’s age, and a blanket designed to be worn by a criminal. After going for a spell, the vehicle arrived at Camp Thủ Đức, a place surrounded by a high wall with barbed wire. I had to pass the night there.

The young security guard slept on a bed next to mine. I was very tired, but I was incapable of closing my eyes; sounds of explosions from some time in the past at the warfront kept going off in my head.

The next day I was questioned again, and I gave the same answers as before. Aside from Bảy, the people questioning me included someone named Đồng, and someone named Phong. All the interrogations were recorded by a machine reserved for the purpose in the next room.

After it had become entirely dark, the police chief, whose name was Thành or Thanh, came by. He wore a severely correct white shirt and seemed to be of high rank. He had come to see me as a pre-release formality. He exchanged a few quiet words with me that I can no longer remember. I noticed that Bảy spoke to this personage with eager servility, and had reported to him that I was not involved in any underhanded activity. He even bade me farewell with a pleasant smile!

But then a few days later when I went back up to Hanoi, I had to report to the A15 Police Station (the place for foreign espionage investigations?) so that I could continue to be questioned about all kinds of earthshaking matters. These interrogations occurred on May 1, May 11 and May 13 of 1991, and were conducted by officers Trần, Hạnh, Mâu and Long.

Thus, about ten years after my memorable meeting with Prime Minister Phạm Văn Đồng concerning Hanoi in Whose Eyes, I was still having a lot of trouble with security organizations.

One afternoon in 1992, a person came whom I had not previously met. He introduced himself as Nguyễn Tiến Năng, the secretary to Prime Minister Phạm Văn Đồng. He said, “The prime minister would like you to come see him in order to discuss something.” I was very bewildered, because I could not imagine why the prime minister still remembered me; and didn’t understand what he might wish to discuss with me.

I came at the time agreed on. He had grown weaker, and his eyesight was not what it had been. He received me alone in his capacious guest room. He asked me about my work and my family.

I said that, thanks to the kindness of Heaven, everything was normal.

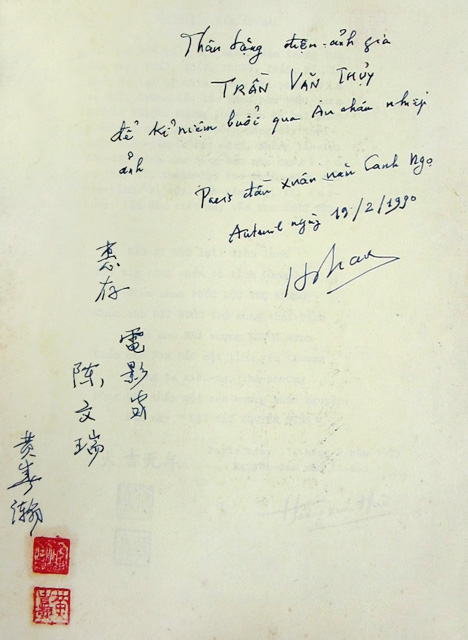

A gift inscription made by the scholar Hoàng Xuân Hãn.

Entering into the matter at hand, he said, “How could everything be normal? I just got a letter from the scholar Hoàng Xuân Hãn in France complaining that Trần Văn Thủy was not being very well treated at home, and urging me to look into it.”

The scholar Hoàng Xuân Hãn and the prime minister had long been close to each other. By chance I had the honor to be the recipient of the concern of both these highly principled individuals, who contributed so wholeheartedly to their country.

I said, “In general, things are normal except for two matters: The first is that the police have been having me report for interrogation a great many times. The second is that the Cultural Affairs Department won’t let me travel abroad, even though I have had almost a dozen invitations from France, and especially Japan, invitations that have to do purely with professional matters.”

Looking worried, the prime minister said “I no longer have any power or position—I’ll find out who is in charge of these matters and speak with them about it. If they’re close acquaintances, I’ll be able to speak with them.” Those words of the prime minister made me very sad. It was a pervasive sadness, hard to put into words.

And yet another story: In 1992, the wife of the French president François Mitterand came to Vietnam as the chair of the Danielle Mitterand Foundation. Before she arrived in Hanoi, the French ambassador sent me an invitation to meet her. I had heard that there would be a meeting between her and a few intellectuals living around Hanoi. It wasn’t clear to me what her intentions were with regard to this meeting, but, for reasons of courtesy, I said a word of thanks and decided to attend if I could do so without too much trouble.

But when the day of the meeting arrived, two people who claimed to be policemen appeared at my house (back then I was still living at 52 Hàng Buồn Street). They said to me that I should not attend the meeting. I asked if they meant “should not” or “will not be allowed to.” They said “will not be allowed to.” I asked why. They said that those were the orders from above—a supremely easy answer that could be used for anything, with anybody, at any time.

I thought that the matter was perplexing in the extreme. If I was allowed to go, then there should have been some previous explanation. If I went, then I would lose time, would have to dress up in a suit, and would have to present a bouquet to be courteous. Nothing in all this would be pleasing to me. The two visitors remained stolidly sitting in my house, not letting me leave, until they got a call from security, informing them that the meeting was over. Only then did they leave my house. Later on I heard that during the meeting people had told Madame Mitterand that I gone on a distant business trip, and was not in Hanoi. Truly laughable! Unfortunately for them, the secretary of Danielle Mitterand, a person who spoke Vietnamese like a native, suddenly paid a visit to me the following morning, and questioned me very carefully as to how it happened that I was not at the meeting, and wrote my answers down in a notebook. His name was Joel Luguern. I heard that he was the foster father of the actress Tôn Nữ Yên Khê, the wife of the famous director Trần Anh Hùng.

Twenty years have passed since then—the police operatives who used tail and question me have surely all retired already and become old men. As I reflect on this, it seems to me that every person has a profession; I have my profession and they have theirs; if we should meet again now over a glass of wine and chat about the affairs of the world, there would surely be many amusing things to talk about.

But as I think more about it, I find I can’t imagine how much of the people’s taxes and how much time and effort on the part of the young have been poured into efforts to “break cases” of this sort. This clearly was a terrible situation!

But as I think about it again nowadays, I find that I must in all fairness thank all those policemen, for if they had made the slightest sign at some junctures, I would at once have been a criminal, and there would have been no occasion to continue those long chats. And this is not to mention the fact that among the security personnel with the power to make decisions and to discuss whether I should be arrested or not, there some people who looked out for me. That is something that I have only recently begun to find out about.

And then by coincidence, just a few months ago, I met police chief Phạm Chuyên again after a lapse of thirty years. In response to invitations extended to him by friends, he came to our montage rooms and looked at the film we were working on: Resounding Melodies of the Ages, Part III.

I can say that Phạm Chuyên is kindly disposed to me, or perhaps even that he reveres me. We chat with each other, go out for pleasure, visit each other’s families, drink beer, and tell stories… We often refer to him as “the magistrate.” He lives in an abandoned and gallant manner. What most impresses me is that he has feelings of special friendship and respect for General Nguyễn Cao Kỳ. He has also protected some intellectuals and artists when they got into trouble.

I remember that thirty years ago in 1983, when Hanoi in Whose Eyes was in limbo, it was shown once in order to get the views of some narrative filmmakers. Many heated opinions were expressed and, for some reason that I don’t understand, Phạm Chuyên, who was then chief of police, was present at the showing as well. When the discussion drew to a conclusion, he came over and squeezed my hand tightly, saying,

“I’m Phạm Chuyên. I can guarantee to you that, whatever may happen, this film will be accepted and will come before the public.”

I should relate as well that only recently my wife went to visit the family of an old friend and schoolmate named Phụng, and found that her whole family worked in the police department. They were close to each other from childhood and lived in the same vicinity near Hàng Bột Street. In the course of a long conversation, they found that Phụng’s son Huy had once in former times been required to stand guard outside my old house at 52 Hàng Bún Street. It was the house of his mother’s close friend, but he had no idea of this. Relating this old story everyone present laughed till tears came. Phụng said to my wife, “If I had known he was guarding your house, I would have told him to go in and sit down, so he would be less miserable!”

I feel sorry for the young fellow and all the others involved. Whether beneath a blazing sun, or in the midst of a drizzling rain with chill winds, he had to stand there and keep watch for something that could never be seen and that never existed. Huy is now a lieutenant-colonel and his two elder brothers are also lieutenant-colonels. His mother Phụng has retired with the rank of colonel; while his father Tuyến has passed away already with the rank of captain.

I had a sworn younger brother named Doãn, Hoàng Trần Doãn, also in the film business, who now teaches in the Stage and Film School. We were very thick with each other during the period when I was making Hanoi In Whose Eyes. But after that he suddenly vanished without a trace for nearly twenty years!

Then one day we met again at a meeting of the Cinema Association attended also by the director Việt Linh, and he openly recounted the following story:

The last night I left your house, it was drizzling outside. I had just jumped on my motorcycle and gone a few meters when a fellow in a raincoat came up to me and patted my shoulder: “Hey! You’re going in and out of Trần Văn Thủy’s house too much!” I was terrified and didn’t dare go to your house any more. Now, on meeting you again here, I feel very embarrassed.

I don’t know how many people who came to my house “had the privilege” of being patted on the shoulder in this fashion, but there were surely quite a few people who avoided me out of fear or caution.

I remember that back in those days, that the director Phạm Hà, an elder colleague of mine, was peddling a bicycle on Hoàng Hoa Thám Street down to Bách Thảo from the documentary film studio while I was peddling up in the opposite direction. On reaching the gate of the Beer house, Hà caught sight of me and at once braked his bike, jumped down and pushed it by hand, saying, “Oh Thủy! You haven’t been arrested yet?”

It has been nearly thirty years since then, but I remember those words as clearly as if it they were printed, and his bewildered look. I was all at sea; I hadn’t the slightest idea how desperate my situation was! I went up to my place of work as usual, greeted everyone as usual, and merrily chatted and joked with them until my friend Lò Minh, a steady person of few words, had to pull me over to a deserted spot and admonish me: “Why are you still so blithe? Do you know no fear?”

How strange! What should I have feared?

And then my studio had to make a detailed report, and had to produce my personal file for the police to examine, and had to cease preparations to receive the honorary designation “heroic work unit.”

It was a wretched business for the film studio chiefs; they hadn’t the faintest notion where or how to look for some sinister enemy force lurking in the shadows.

Having told the story up to this point, I must add, for purposes of clarity, that the gentleman most eager to openly denounce Hanoi in Whose Eyes were three in number: Mr. Hoàng Tùng, Mr. Văn Phác, and Mr. Hà Xuân Trưởng. To say that they were “open” in their denunciations is to imply that there were others who were not open. These gentlemen never gave me an opportunity to say anything to clear my name; they just looked at the film, reached a conclusion, affirmed it, and issued directives… But now that I think it over, I feel that I should feel indebted to them for doing me a favor. If those gentleman had magnanimously refrained from chastizing the film, or had watched the film and ignored it, in a “mackeno” or “macmeno” fashion,1 if they had not made a great noise about it, then not even a ghost would ever paid attention to that eccentric and ill-conceived film. When they blew things up in that fashion, and looked upon the film as a good opportunity to “demonstrate their political stance,” they had no idea that they were providing that fellow Thủy with notoriety…

Nearly twenty years later, when the affair had cooled down, and I was making a film about Professor Hoàng Minh Giám, I went with my film crew to interview Mr. Ha Xuân Trưởng in his home; and this was also an opportunity to visit him. In his last years, he was not in good health. When we had finished shooting the scene and were packing up our equipment, I went into his room to bid farewell to him.

He was very embarrassed, and evidently wanted to say something to exonerate himself: “In those times… in those times…” he began, but was unable to add anything more. I politely expressed a hope that he would take care of his health and departed with my colleagues.

It’s as plain as can be that this filmmaking profession of mine is but a grain of sand in the vast ocean of society, so why should it be taken so solemnly, why should it be ridden with so many messy problems? And what about great affairs of state? How could it be reasonable for us Vietnamese to keep on reserving our time and energy, from one generation to the next, to wrestle with confused problems of this nature? And the most melancholy fact of all is that even now, we are affected with the same calamity.

The owner of the café Lộc Vàng is unable to restrain his tears when listening to the song “Autumn Raindrops” right in his café, and remembering the ten years he spent in prison for “the crime of listening to yellow music.” (a scene in the film Resounding Melodies of the Ages, Part III).

Just recently, we completed making Part III of a film in several parts entitled Resounding Melodies of the Ages, to help celebrate the thousandth anniversary of the founding of Hanoi. To introduce a number of love songs that had been strictly banned for many decades, I wrote the following:

“Prohibitions arising from taste, or from tendencies of thought, brought much pain and misfortune to authors, and to their literary and artistic productions; and this continued for half a century—but, through immense good fortune, these things were no one’s fault!

And it was not just authors and their works that met with misfortune, but people who appreciated them as well!

When the film was being mounted, some found the above passage a bit hard to take, but I stubbornly defended it. After all, I said in the passage that this was no one’s fault!

When the celluloid film was made the words were still preserved, but several months later I learned that they had cut the words out prior to distribution (October, 2012). And no one had said a word to me about this. I was deeply afflicted, and couldn’t eat or sleep for a month. To behave like that with each other is to do an injustice to life itself.

And this was something that happened thirty years after the controversies surrounding Hanoi in Whose Eyes. There had been no advance in enlightenment.

Sad! Truly sad!

I suddenly remembered that many years before, at the beginning of The Story of Kindness the cameraman Đồng Xuân Thuyết, before passing away, had read us a passage from the book Rules for the Ages by Đumbatze that he was holding in his hands:

“A man’s spirit is a hundred times heavier than the body, so heavy that one man alone cannot carry it. For that reason, we must try to help each other, while we are still alive, so that our spirits may become immortal. You help my spirit towards immortality, and I help another, who then helps yet another person, and so on without end.”

That made me remember further things, and I said the following to the Americans Michael Renov and Dean Wilson, during their six-month long interview:

I love this land, and I want to make this land even more beautiful. I am consumed with the wish to make human life worthy of the sacrifices that have been made for it…

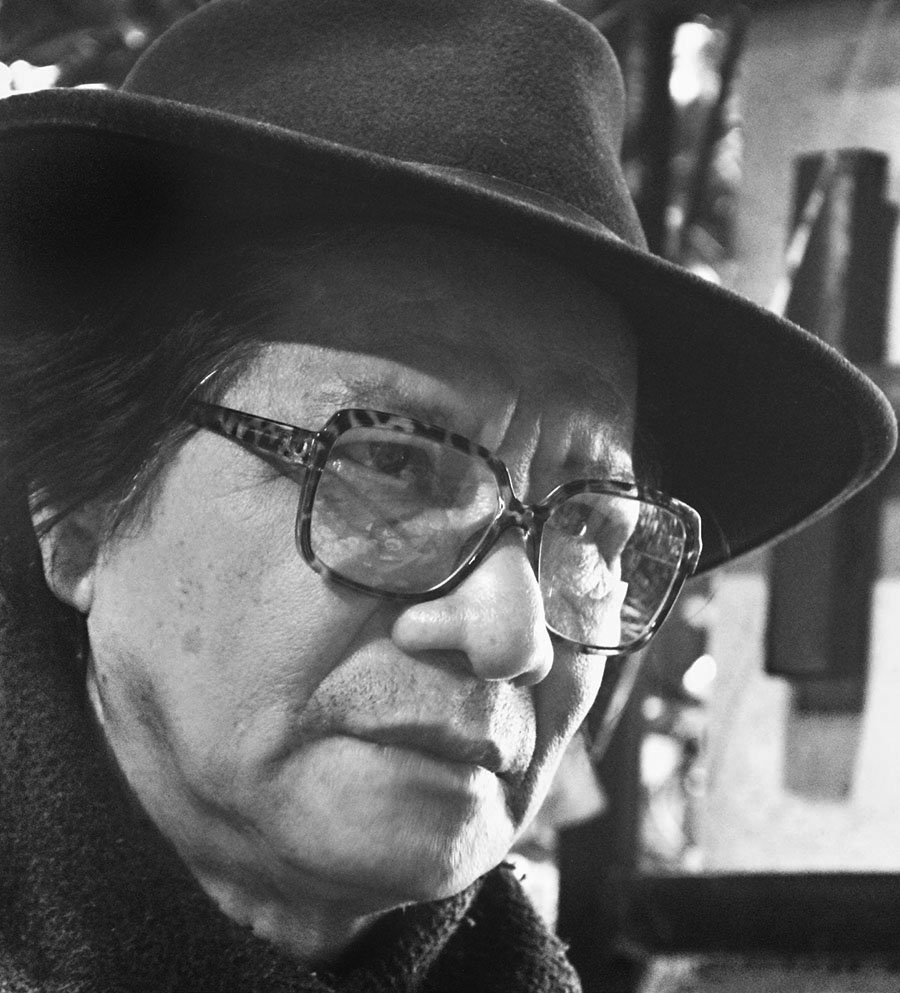

Trần Văn Thủy in 2013.

I have a deep and earnest love for the land that gave me birth. That is the point that I start from.

And last of all, instead of thanking my readers, please allow me to refer to the concluding words of A Story From the Corner of a Park, a film that shows how a Catholic family rises above an unhappy situation brought about by the after-effects of Agent Orange.

We were unable, until we had finished making this little film to entirely understand why, and by what means these people were able to rise above the wretchedness and challenges of life in such a simple and graceful way.

Could it be because of their faith?

I don’t dare to affirm that this is what it was; or if it was because they knew enough to honor and revere peace in the spiritual life of a human being.

I have loved the language of my land

From the time I first saw light,

Oh people…

My gentle mother with her distant lullabies…

Ah, ah, oh…

The lullaby of a thousand lives,

The language of my land,

Four thousand endless years of joy and sadness,

I laugh and weep with the changing fortunes of my land.

[This is a quotation from the lyrics of “Tình Ca,” (“Love of Country”) a famous song by Phạm Duy]

Can the songs of former times help to assuage our hearts, when a human life is of no more consequence than the destiny of a worm or an ant?

| 1. | These words are based on Vietnamese slang expressions of contemptuous dismissal. |

Order In Whose Eyes from the University of Massachusetts Press, or from Amazon.

All text and images are © 2023, Trần Văn Thủy, all rights reserved. Written permission is required for any use.